COP26 (26th Conference of the Parties) negotiations have finally come to an end! Two long weeks during which speeches, promises, and negotiations intertwined to result in the Glasgow Pact.

Following a COP is an enriching experience on all levels. Reading primary source information is one thing. Reading or listening to the media coverage of the event, political speeches, and various interpretations of the event is another. According to Barbara Pompili (French Minister for Ecological Transition) and Boris Johnson, COP26 was a success. According to others, like the delegates from the Marshall Islands, it was a death sentence. The eleven pages of the Glasgow Pact can and will be interpreted differently by everyone.

The objective here is to give an overview of the main conclusions of COP26 with enough sources so that you can dig further into each topic. I will not go back over the objectives of COP26 in this article, nor its lousy organization and all the greenwashing around it. I already did in this article.

Foreword: a COP is not there to save the world

“It’s useless!” “It’s crap!” “They’re not gonna change a thing!” Before it had even started, everyone and their mother had an opinion about COP26. Maybe rightly so. CO2 levels have been rising steadily, yet, so far, previous COPs have not been able to turn the tide.

On the other hand, let us imagine a scenario where COPs did not exist. States and companies would continue to do whatever they please without any constraints. Citizens would have no counterpower to push back with. Similar opinions were expressed about the Paris Agreement during COP21. Yet the conclusion is the same: to say that COPs are useless is false.

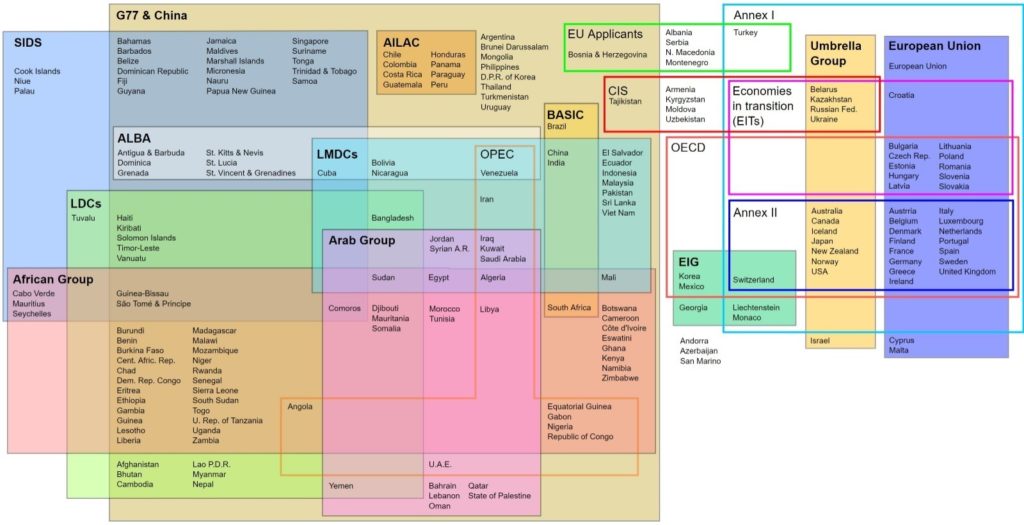

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) plays an important role and will continue to do so in the decades to come. Before going into the details about COP26, here are some helpful reminders:

- A COP is (in principle) inclusive and allows everyone to be on the same level. In other words, Fiji is supposed to have as much say as the United States.

- The final conclusions (the Agreement) are accepted unanimously. The challenge lies in getting 200 parties to agree simultaneously.

- In negotiations where so many countries are involved, peer pressure can build up. If a country is single-handedly trying to quash an agreement, it will systematically be singled out by the others. As was the case here with India and coal (we will come back to this).

- Because of their decision-making power, other bodies can have as much weight as a COP e.g., the World Trade Organization, Free Trade Agreements between countries, bilateral agreements on deforestation or methane, etc.

- A COP is not an end-all-be-all. Every country, company, NGO, and citizen has a role to play.

The diagram below shows countries’ alliances and common interests:

The devil is in the detail

If you have not followed climate negotiations before, here is what you should know: every single word is debated, disputed, and can be the subject of many hours, or even days, of negotiations. The stakes are high. Just like for the Summary for Policymakers (SPM) of IPCC reports, “each sentence validated [in the SPM] can potentially have an impact of several billion for several countries.”

Moreover, you will notice a more or less significant discrepancy between the first draft and the final version of the agreement. This is common and can sometimes be very annoying. For instance, the term “emergency” was removed from the title “Glasgow Climate Pact”. Journalists also spent hours debating whether using “urges” is stronger than “requests.” Shouldn’t we simply require countries to reduce their GHG emissions?

In other words, to best understand climate negotiations, having knowledge of law + politics + geopolitics + history + climate + manipulation + hypocrisy + lie detection is the bare minimum. You may get lost otherwise.

Let us now go into detail on each key aspect of this COP26.

Towards a +2.4°C world?

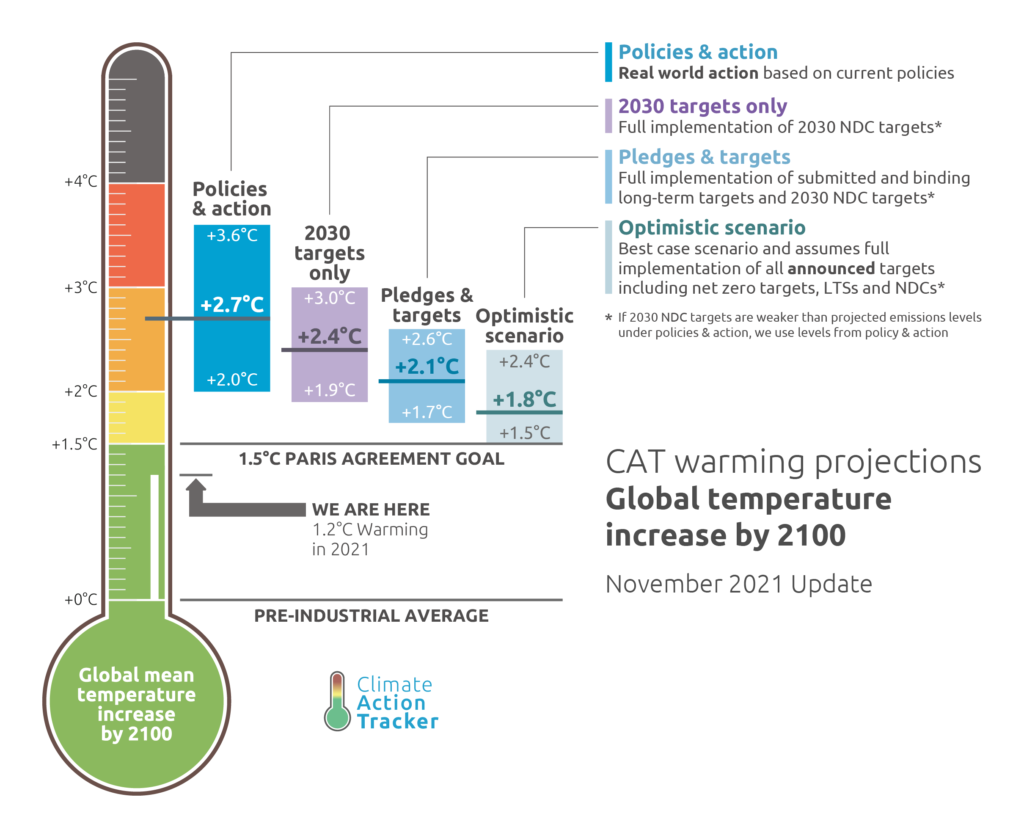

Before the start of COP26, States’ commitments and policies were leading us to a +2.7°C world by the end of the century. According to Climate Action Tracker, new pledges (Nationally Determined Contributions, NDCs) put us on track for:

- A +2.4°C temperature increase by the end of the century (+1.9°C to +3.0°C range) if the current 2030 targets (without long-term pledges) are met;

- A +1.8°C temperature increase by the end of the century (+1.5°C to +2.6°C range) if all the announced net-zero commitments or targets under discussion are implemented.

It is still highly insufficient and full of promises that do not commit anyone to anything since sanctions are still not a thing. But on paper, it is an improvement.

Besides, interpreting States’ announcements has proven to be a… tricky game. India’s announcement of its carbon neutrality for 2070 caused quasi-unanimous laughter. “2070”! However, this is rather good news: it has allowed us to go under the symbolic +2°C of global warming. Six years ago, at COP21, we were on track for +3.5°C of global warming.

Of course, we must remain cautious on many levels, especially on the method and accounting of NDCs. While India announced it would reach carbon neutrality in 2070, it did not communicate any precise plans on how it would achieve it. Nor do we know whether this pertains only to CO2 or all greenhouse gases! Since actions never match promises, we must demand more clarity about States’ short-term action plans.

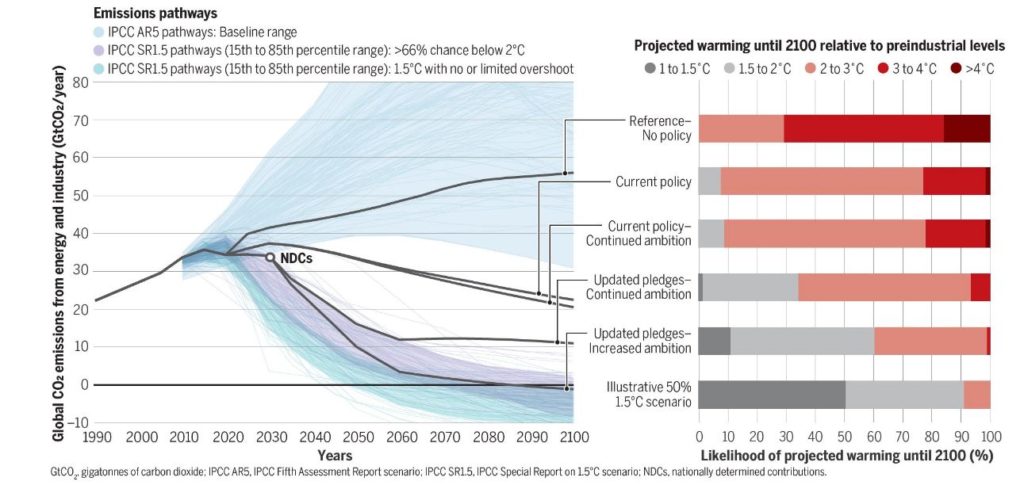

to limit global warming to + 2°C?

There is a world of difference between the International Energy Agency’s optimistic scenario of +1.8°C and the +2.7°C that we are likely to experience by the end of the century. Nevertheless, thanks to the updated pledges, we have never had a better chance of reducing global warming well below 2°C.

Focus points

Regarding mitigation (emission reduction), the Glasgow Pact asks countries to have strengthened their emissions reduction commitments by 2022. It recognizes the need to reduce global carbon dioxide emissions by 45% by 2030 and achieve net-zero carbon neutrality around 2050.

But NOT A SINGLE COUNTRY has a concrete and +1.5°C compatible plan to reduce emissions without it being accompanied by negative emissions or the appropriation of another country’s lands, forests, or oceans. As a reminder, without a precise, short-term action plan, 2050 carbon neutrality is but an illusion.

Second, on methodology. The figures presented above are not as simple as they seem. The results are obtained using specific models, with specific assumptions, and under specific uncertainties. Let us avoid the “Illusion of Knowing” at all costs.

Finally, a great piece by the Washington Post came out during COP26, showing that some countries were underreporting their greenhouse gas emissions in their reports to the United Nations. Philippe Ciais, a researcher at the LSCE, stresses that we could be missing a quarter of global emissions.

Lack of capacity and means of some states on the one hand. Blatant dishonesty and lies on the other. Just another reminder that promises only bind those who believe them.

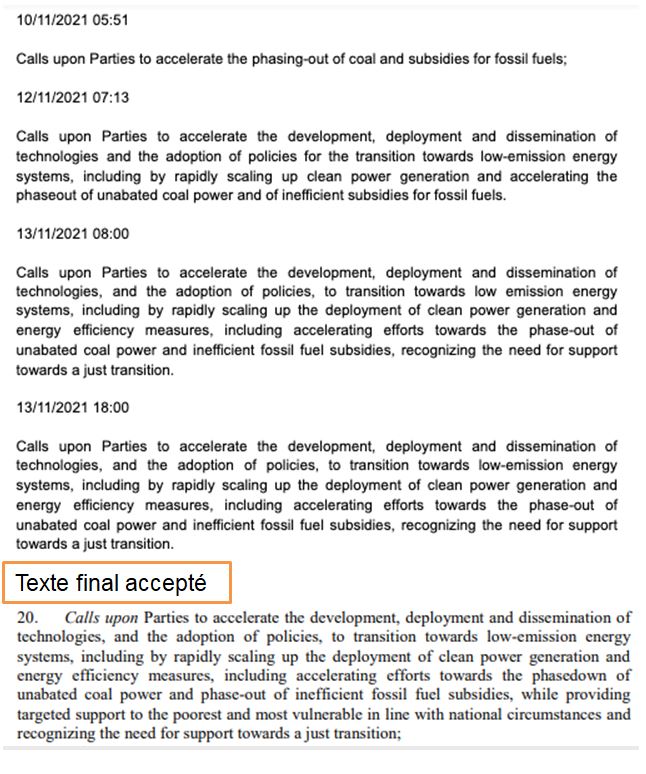

“Phase out”, “phase down”: a coal frenzy

Programming the exit of coal was one of the objectives of this COP and politicians were brave enough to do it. How groundbreaking! Well, almost.

Fossil fuels had already made an appearance in previous texts, like in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol and in the draft 2015 Paris Agreement, before exporting countries, led by Saudi Arabia, insisted that the term “fossil fuels” be removed. In Glasgow, “coal” stuck. But it remains to be seen how.

In the last three days, the text has been changed four times. We went from “accelerate the phasing-out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuel” to “accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”.

To understand the subtleties:

- Unabated: in coal-fired electricity generation, abatement is generally understood to mean the use of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology. In other words: no CCS technology = no new subsidies for coal plants or projects.

- Phase-out / Phase down: we have gone from “exit” to “phase down”. There really is no ambiguity here. Given the impact of the goal on climate change, this is a mini-scandal.

- “Inefficient”: but who is to decide what is inefficient? And according to what criteria?

- No timeline? No timeline. However, this kind of decision does carry weight: things are heating up for coal, and financial actors will consider this decision before lining up billions for new projects.

Much needed clarification: the track record of CCS projects for coal-fired power plants is not exactly stellar (read about it here and here). But after all, why not? If it allows some to justify the unjustifiable.

Finger-pointing at India: rightly so?

The Western press immediately and almost unanimously pointed fingers at India (and China) for having changed the terms of the Glasgow Pact at the last minute. This is the game of climate negotiations: everyone has to agree, and negotiators know this very well.“Either you agree to move from ‘phase out’ to ‘phase down’ or we will not sign, and that is a tremendous failure for your mandate”. As always, it is a little more complicated than that.

The United States and China first used the term “phase down” in their bilateral climate agreement, adopted with great fanfare amid COP26. In the closing of this COP, which lasted more than an hour in the plenary hall, China said that it wanted the text on coal use reduction to be closer to what it had agreed to in a joint statement with the United States.

However, it was up to India to clarify the last-minute change. Instead of agreeing to a “phase out” of coal-fired power, Indian Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav read a new version of the paragraph. In this new version was the term “phase down”. This wording was subsequently retained in the final text approved by nearly 200 nations.

Although several countries, including Switzerland and the Marshall Islands, immediately complained that other delegations had been barred from reopening the text, India and its allies prevailed. COPs are inclusive, right?

The world is burning and we are staring at India

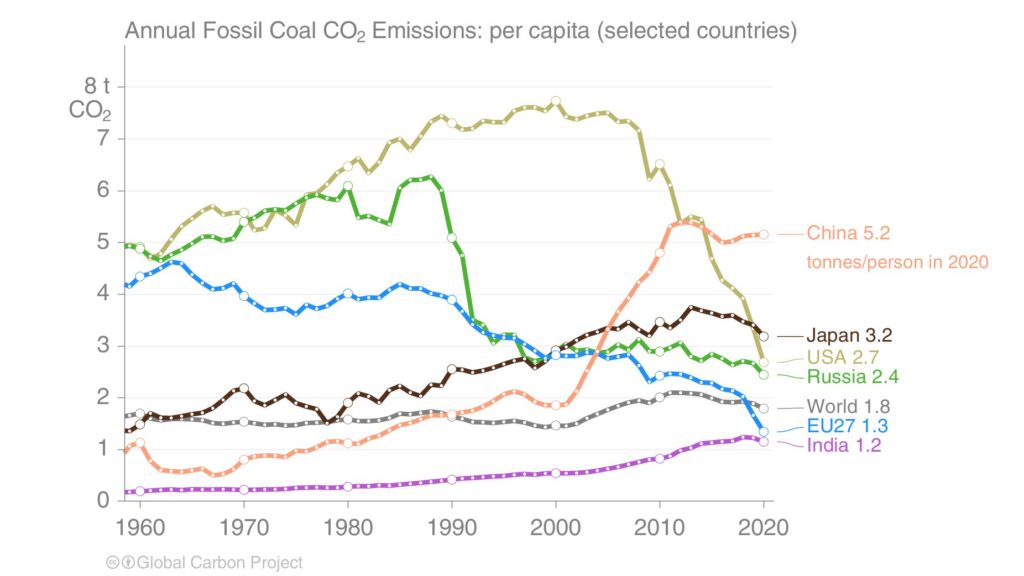

It is striking to see the Western press pointing fingers at India without doing any kind of self-criticism. India is accused of all evils. Yet it has very low per capita emissions, and a strong regional dependence on coal (70%+ of its electricity)… part of which is imported from China.

Moreover, to lash out at India when it is only responsible for 3% of historical emissions, coming from the United States and Europe, is, to say the least, ballsy. Especially when these very countries refuse to provide the necessary financial aid to developing countries, including India.

Two other important points. First, as Arnaud Gossement (French lawyer and professor) pointed out: “it is a very general obligation, expressed in a decision without direct legal standing and valid only for projects without CCS and without a timeline”, with or without the Indian amendment. Second, why is there so much attention on “phase down” vs. “phase out” for coal, but not on all fossil fuels? Point a finger, three point back.

What about oil? What about gas?

A 10-year-old child could understand that to stop global warming, we must progressively get out of fossil fuels. COP26 negotiators apparently did not, for they did not manage to include the words “oil” or “gas” in the Glasgow Pact. None of this was out of ignorance: it has been done on purpose for more than 20 years.

On another note, we had to wait until the end of COP26 for France to join 39 countries in an agreement to end foreign financing of fossil fuel projects without carbon capture technologies by the end of 2022. This is estimated to represent around USD 15 billion.

The second week of negotiations also saw the launch of the BOGA (“Beyond Oil and Gas”) Alliance, which brings together a dozen countries, including France. Much ado about this announcement. Looking in detail, the members represent barely 1% of global oil production.

The current French government, which has been condemned for climate inaction, used its usual “both… and…” strategy throughout this COP. The most striking example was Barbara Pompili’s grand announcement to the French press that France is joining a coalition to end public subsidies to fossil fuels abroad by the end of 2022. Great news! But in the hours that followed, we got to hear a bit more about this initiative:

La bonne blague ! Avec ce gouvernement les fausses joies ne durent plus que quelques heures.#cynisme #COP26 #fossiles #ArcticLNG2 https://t.co/1U5D1Brf2c

— Delphine Batho (@delphinebatho) November 12, 2021

Ensuring that the government’s announcements are aligned with French law will be paramount. Let us also remember that this only commits public subsidies. For now, French banks can continue to carelessly pour tens of billions into fossil fuel subsidies every year.

Unfortunately, France is not the only country doing this. During COP26, the European Union approved 30 gas projects representing a total of 13 billion euros. Definitely worth pointing the finger at India, wasn’t it?

Conclusion: it was undoubtedly a failure for oil and gas not to be mentioned in the text, although it’s easier said than done. Also problematic was the fact that the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT), a system that actively threatens the Paris climate agreement, was not mentioned once. I am sure the 503 fossil fuel industry lobbyists present at COP26 are delighted by this.

Methane is finally mentioned

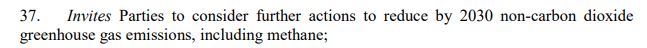

The IPCC having focused its last report on it last August, methane was one of the main issues of COP26 and, in a historic first, made it into the final text.

Moreover, the Global Methane Pledge was officially launched and joined by 109 countries committing to reducing their methane emissions by 30% by 2030 compared to 2020 levels. Although some key countries are missing, including Russia, this is still great news. As a reminder: a 50% decrease in global methane emissions is needed to reduce global warming by about 0.2°C by 2050.

Source: Piers Forster

These recent developments show us, once again, that the future of climate is indeed in our hands and that inertia is primarily political. Unfortunately, almost no details were given on how countries plan to achieve these goals. Moving forward, countries must provide further detail about their commitments and be transparent about the calculation methods used.

NEWSLETTER

Chaque vendredi, recevez un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

+30 000 SONT DÉJÀ INSCRITS

Une alerte pour chaque article mis en ligne, et une lettre hebdo chaque vendredi, avec un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

The 100 billion fall by the wayside, again

One of the objectives that would have made COP26 a success was to finance developing countries to the tune of USD 100 billion per year. This has been in the works since 2009. But once again, ‘rich’ countries failed to agree during the two weeks of negotiations:

“Deep regret” will not make up for this. As a reminder, these countries will need trillions of dollars to finance mitigation and adaptation. The official argument to defend this loss is pretty pathetic. It is inexcusable and unjustifiable.

How can we possibly explain to these countries that there is no money, despite hundreds of billions suddenly appearing when COVID started threatening our economies in January 2020? Is COVID really a bigger threat than climate change? We can only hope that Northern countries manage to track down the 11 trillion in tax evasion from the Pandora Papers…

In the meantime, developed countries are “urged” to deliver on the USD 100 billion goal urgently and through to 2025, however, no compensation for the shortfall is stipulated.

Loss and Damage

Loss and Damage is considered the third most important component of climate change action, after mitigation and adaptation. It refers to the area of action wherein countries already impacted by climate change demand compensation for climate hazards to which it is impossible to adapt. The amounts requested are totally justified and echo climate justice: countries emitting the most should pay for the damage they cause and will continue to cause.

The Santiago Network was created during COP25 in Madrid, with ties to organizations that could support the loss and damage. Robust action was expected at COP26 but, as usual, rich countries failed to deliver.

A proposal to create a “Glasgow Loss and Damage Facility” had been submitted by 138 developing countries (representing 5 billion people) and was even included in the draft of the Glasgow Pact. However, it was scrapped from the final text by the United States, the United Kingdom, and the European Union.

States were asking for billions. They ended up with a few million and “a dialogue”. In another universe, Jeff Bezos and Richard Brandson are spending multiple millions of dollars to fly into space. #InclusiveCOP

N.B.: As we know, companies and states have been sued within the framework of the Paris Agreement – including the current French government which has since been condemned for climate inaction. Admitting that irreversible damage also affects rich countries is likely to open the door to lawsuits and claims from countries that suffer from climate hazards.

End of deforestation in 2030: good news?

On November 2, more than a hundred countries committed to ensuring that deforestation is completely stopped globally by 2030. More than 10 billion euros of public money and nearly 6 billion of private money could be allocated to this cause over 2021-2025.

However, there is once again reason to be cautious about these announcements. These commitments echo the New York Declaration on Forests and are non-binding. Will States really implement action plans against deforestation in the coming years? Could Bolsonaro, even if he wanted to, totally reverse his policies, despite the whole economic system of deforestation in the Amazon being corrupted?

French researcher François-Michel Le Tourneau makes a compelling case regarding the amounts allocated:

Two comparisons can be made. The first is France’s effort to fight illegal gold mining in French Guiana, which amounts to 70 million euros per year. If an equivalent effort were to be made for the Brazilian Amazon, which is 50 times larger, it would require 3.5 billion euros each year, which is more than the amount proposed in Glasgow for all the world’s forests. It is clear that these funds will not be enough to tackle the issue globally.

Second, the NGO Global Witness has conducted an investigation showing that international financial institutions have invested more than USD 157 billion in companies linked to deforestation between 2016 and 2020. Annually, that is at least ten times more than the Glasgow commitment...

As with the other announcements, we will have to follow the actions of the signatory countries in the coming months to check whether promises have been transformed into action on the ground.

Carbon markets: an agreement on Article 6, at last

After more than four years of negotiations, countries have finally reached an agreement on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which deals with international cooperation, notably via carbon markets. It is extremely difficult to obtain a consensus on this article because the interests at stake are so diverse. Changes were made right up to the last day, with the threat of multi-billion dollar financial interests potentially scuppering the agreement.

A dedicated article will be published on Bon Pote because it is impossible to grasp the ins and outs in just a few lines. But here are the main points to remember:

- Article 6 is the driving force behind the Paris Agreement’s international cooperation. It is vital because countries can reduce emissions quicker and with far more results by cooperating than they can alone.

- The agreement addresses how countries work together to reduce their emissions and can trade those efforts with each other, including by selling the credits to companies.

- Offsetting means that states and companies responsible for the most emissions can continue to emit as much without making any mitigation efforts. This has been known since the Paris Agreement.

- Regarding carbon markets, which allow rich countries to buy “offsets” (such as tree planting) to avoid the cost of reducing emissions, the agreement does fill in some gaps. These include slightly stricter environmental integrity rules and some protection for Indigenous peoples.

- There is a partial cancellation of credits left over from the old Kyoto Protocol and a partial cap on new credits. This means that carbon credits obtained since 2013 can be reused via the Paris Agreement, up to 320 million tons of CO2 equivalent.

Many NGOs have denounced the risks of greenwashing tied to this agreement, which could serve as an alibi for States and companies. After all, why reduce your emissions when you can compensate for them at a low cost?

If you want to learn more, you can read this article from Carbon Brief or this summary in French from Thomas Baïetto.

Let’s not forget…

The Glasgow Pact may only be ten pages long, but dozens of pages could be written on each point to decipher the complexity of the negotiations and their consequences. Other important moments from these two weeks went a little under the radar.

First, on states’ transparency efforts. From 2024 onwards, the framework for publishing pledges (NDCs) will be much stricter, and states will have common schedules and formats. This means that everyone will be able to see what other countries are doing. If the numbers are published correctly, empty promises could be welcomed with a little less fanfare in the years to come.

Second, many scientists welcomed the fact that the findings of the IPCC reports were included in the text for the first time. Point 3 below emphasizes that global warming is not a 2050 issue and expresses concern that at +1.1°C of global warming, impacts are already being felt in every region. Let’s hope that the physical limits will be taken into account a little more than the usual blah-blah-blah of States that tend to hide behind greenwashing.

On the other hand, some news never left the headlines,like the “Agreement between China and the United States”. A first! Unfortunately, this is not an agreement, but rather a simple declaration, which is not a first: the two states had produced a similar announcement before COP21.

There were also thousands of reactions following the final speech of Alok Sharma, president of the COP26, who held back his tears at the closing of COP26:

An emotional Alok Sharma says he is "deeply sorry" for the way the #COP26 conference has unfolded.

— Sky News (@SkyNews) November 13, 2021

Holding back tears, the COP president says "I understand the deep disappointment but it is also vital that we protect this package."

Read more: https://t.co/qbtRXxkCLQ pic.twitter.com/5RmKuTFlu0

His tears were most certainly sincere: global pressure for two weeks, little rest, grueling negotiations… Alok Sharma’s sense of humanity at COP26 was in sharp contrast with his decisions to block several laws in the United Kingdom to fight climate change. I am really looking forward to seeing French president Emmanuel Macron cry for the planet while we take stock of his five-year term.

So, was COP26 a success or a failure?

Everyone will have their own opinion on COP26: unprecedented victory for some, monumental failure for others. This COP has brought some good news, but also some very bad news. Amid a climate emergency, anything that does not actively plan for an exit from fossil fuels is, in essence, insufficient and criminal.

The fact that rich countries still could not manage to finance the USD 100 billion per year that had been in the works for 12 years is scandalous. So is the ridiculous amount of money planned for ‘loss and damage’. COP26 was anything but inclusive. Once again, a minority of countries’ interests dominated over those of a majority of the planet’s inhabitants. Some countries did not even wait a week to suggest that they would not respect the promises made at COP26… Surprising? Not really.

We must not expect miracles from COPs and should resolve ourselves to the fact that most solutions will come from elsewhere, especially from citizen mobilization. We must continue to activate all possible levers to fight climate change, at all levels of our societies. The bets are in: neither COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh nor COP28 in the United Arab Emirates will result in a plan for a gradual exit from fossil fuels.