In recent years, we have seen a clash between individual and collective actions.

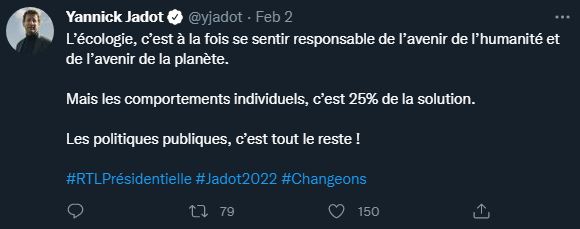

After hearing in 2017 that “100 companies are responsible for 71% of emissions“, we now hear “individual actions are responsible for only 25% of emissions, collective ones for 75%!“. This 25% is claimed by environmental activists, public figures (Gaël Giraud, François Gemenne, Jean-Marc Jancovici) and politicians, such as Yannick Jadot:

Unfortunately, this figure is often misused by those who mention it, hiding the complex responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions. Are individual actions really responsible for 25% of emissions?

Where does this 25% figure come from?

Responsibility for emissions is a debate as old as climate change. However, quantifying and attributing it is another matter. Regarding this 25%, Moran & al stated in 2018 “the results suggest that adopting these consumer options could reduce carbon footprints by approximately 25%“.

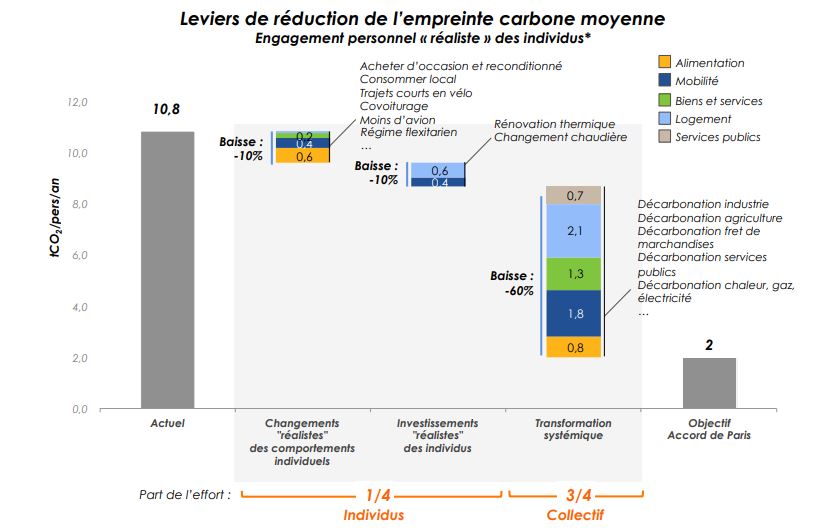

However, in France, this figure systematically refers to the article from Carbone 4, Doing your fair share for the climate, written by Alexia Soyeux and César Dugast in June 2019. The study surpassed the expectations of both authors, with over 62,000 readers.

What does the study Doing your fair share for the climate say?

The study aimed at “questioning the relevance of the discourse of over-responsibility of individuals emanating from certain political or economic structures“, declared César Dugast to Bon Pote.

Despite what one may hear, the messages of the study are very clear:

The battle can only be won if it is fought on all fronts. And in order to know who can act where, and how to manage priorities, it is essential to have the right orders of magnitude in mind.

“Individual actions, whether they are behavioral changes or household investments, are both inevitable and yet insufficient.”

Individual actions = 45%?

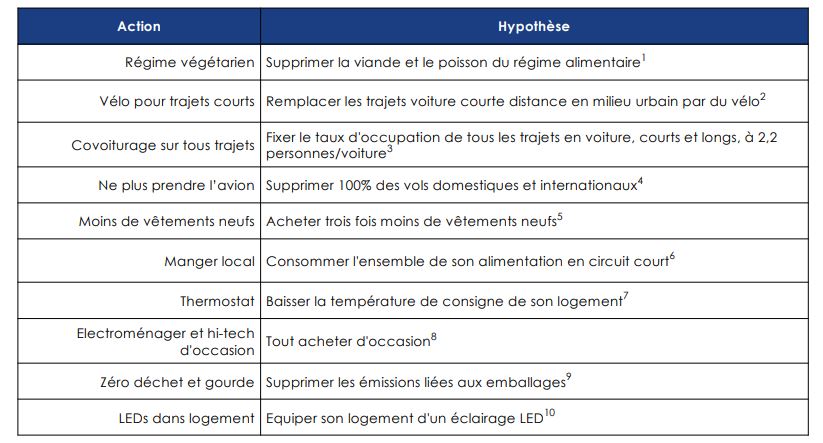

By contrast to the 25% that is constantly repeated, when reading the study one realises that the real impact of “heroic” individual behaviour can reduce emissions by up to 45%, with the assumptions for each action below:

Source: Study Doing your fair share for the climate by Carbone 4

According to César Dugast, “Actually, 45% should be used instead. While keeping in mind that this is inevitable, necessary, but also insufficient“.

This study had the merit of doing two things Firstly, to give orders of magnitude, which are extremely useful for prioritizing our actions. Second, emphasize the need for both individual AND collective actions. Despite this, the communication around this study is often wrong, as if the study had not been read after all.

1 / The study Doing your fair share for the climate is not scientific.

First and foremost, be aware that Doing your fair share for the climate is not a scientific study. It has actually never been presented like that! However, not being published in a scientific journal does not mean it is not of quality. But quoting figures (like this 25%) at the same level as the IPCC Working Group 1 synthesis works can become problematic.

As with any study or calculation, it is important to understand the assumptions made and the limitations. This 25% is only possible in a static world, and can hardly be representative of a world as dynamic and complex as ours. We could also note that this is an attributional rather than a consequential Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) approach.

Carbon Responsibility: how to interpret it?

Attributing greenhouse gas emissions to anthropogenic activities is a risky exercise: who emits? who is responsible for it? At first sight, it is enough to look at where the emissions take place: mines, steelworks, cement factories, aluminum smelters, agriculture, transport, power stations, etc. This is the approach adopted by the international community, embodied by the UNFCCC in relation to carbon accounting, which brings together annual national inventories of greenhouse gas emissions.

But a national economy only emits because its population consumes the goods and services produced there, so the carbon footprint approach is used as a reference when analyzing the impacts of household consumption.

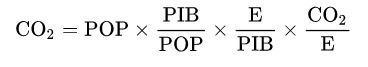

This consumption is roughly proportional to the income level, which appears as the GDP/population ratio (in €/capita) in the famous Kaya equation:

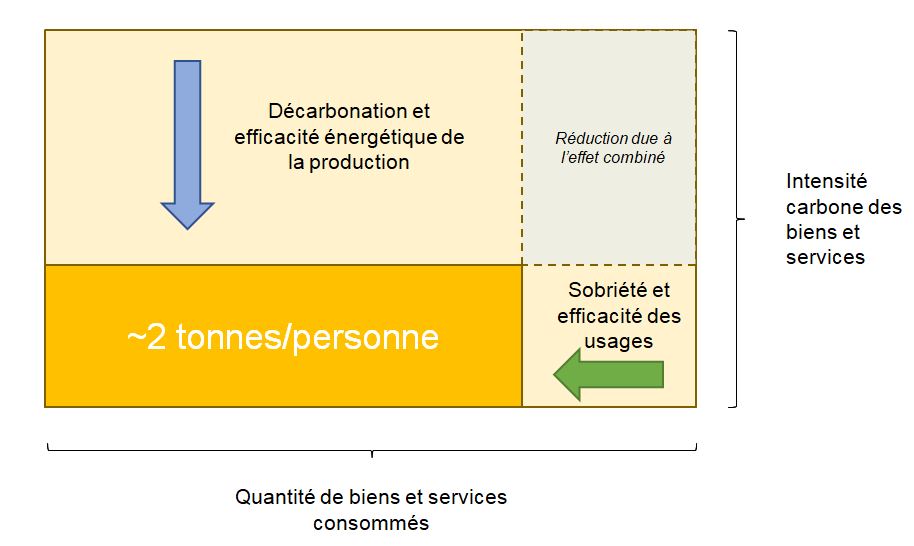

By simplifying, we can neglect the population factor (whose influence is the subject of an entirely different discussion!!). This very simplistic approach reveals the two major levers for decarbonization: final consumption (households) and the carbon intensity of production.

Combined Responsability

The total impact caused by production/consumption is thus comparable to the area of a rectangle that can be reduced by decreasing its height or length: the two levers do not just add up but combine. For example, using your car less (sufficiency) is good, switching to electricity (decarbonization and efficiency of use) is good, but doing both is better! And encouraging public authorities to set up infrastructures that favor cycling or public transport… That’s even better! We will come back to this.

There is no hierarchy between measures in the sense that any initiative that would ultimately lead to decarbonization is a good one to take; the debate about who is responsible for emissions (who should act?) is just another excuse for delaying action against climate change.

NEWSLETTER

Chaque vendredi, recevez un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

+30 000 SONT DÉJÀ INSCRITS

Une alerte pour chaque article mis en ligne, et une lettre hebdo chaque vendredi, avec un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

2/ The Precarious Communication around Individual Actions

This 25% figure has been repeated many times over the past two years to a very large audience (Julien Doré, François Gemenne at Hanouna’s show, Yannick Jadot, etc.) with the result that people repeat it without having obviously read the study or understood the figure. This is a clear example of The illusion of knowing, which is the result of oversimplified information on the complexity of climate issues and the responsibilities attribution.

It is clear that only individual actions are insufficient. Environmental activists are right to point this out and to call on public authorities and companies: everyone has a role to play. On the other hand, not a day goes by (not a single one!) without a message on social media saying ‘it’s not up to individuals to act, it’s up to the system’.

The authors wished to “avoid falling into the opposite trap, i.e. the promotion of under-responsibility, by making it clear that individual actions were necessary, although insufficient“. This is obviously not the message that everyone remembered, but it is almost inevitable: the race to make excuses for not doing anything for the climate is a daily battle.

If let a person who doesn’t want to change understand that individual actions are insufficient, they will jump at the chance to tell you that it is up to others to act. This is also true for Total who asks citizens to delete their emails, or for your sister who flies to Punta Cana because “shit, we only have one life, ask Total to pollute less“.

The love of round numbers

As you may have noticed, numbers are often “round numbers” in communication. This is not necessarily very scientific, but it is very effective. Take for example François Hollande’s 50% nuclear power in the French electricity mix. Why this 50%? Why not 52%, or 48%? Unfortunately, Mr. Hollande has never been able to provide a quantified rationale for this decision or ambition. But this 50% is much better remembered than if it had been 51.43%.

©STEPHANE DE SAKUTIN/POOL/EPA/MAXPPP –

Another more recent example with Boris Johnson: “why are the numbers so round“, who seems to have changed his mind about climate change emergency by watching 11 slides. Moral of the story: if a number is round, it is more likely to be the result of a political calculation than a scientific one. This should call for the utmost caution, especially in order to avoid miscommunication.

The individual actions propagation effect

Not only are individual actions inextricably bound up from collective actions, but they can even lead to the latter. We had seen that politicians rarely (never?) took initiatives on their own and are content to engage in political recuperation. This is the so-called social tipping point.

Structural change happens because people see an interest in it or have clearly expressed it. Seeing an interest, politicians follow. Of course, this tipping point is heterogeneous. Sometimes it takes 10% of the population, sometimes only a few individuals.

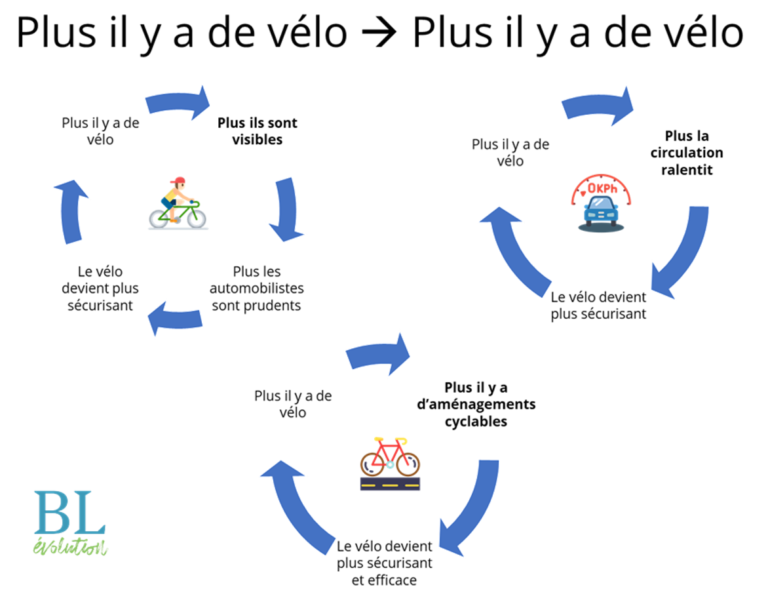

An excellent example of this is bicycle mobility. We saw in our focus cycling that more bikes, and therefore individual actions, could lead to structural change:

Examples of individual actions are illimited and that should not be underestimated or singled out, as is all too often the case. How many people in your circle have followed and imitated your commitment after you stopped eating meat? Stopped flying? Changed jobs to be more in line with your values?

The last word

In recent years, we have seen a clash between individual and collective actions. Constantly blaming one another and making excuses is counterproductive and only prolongs climate inaction.

« It’s up to companies to make an effort! The same goes for the State! ». Well, not quite. It is up to everyone to make an effort, as much as they can. It is certain that responsibility for carbon emissions is common, but differentiated: some are more responsible than others. But to say “100 companies are responsible for 71% of emissions” or “individual actions account for only 25% of emissions, the collective 75%!” does not make any sense. Individual and collective actions are inextricably bound up and indispensable: we will need both, and everyone.

The logic is always the same. Understand that every action has an impact, and keep the right orders of magnitude in mind. Some things cause more pollution and emit greenhouse gases than others. This is one of the reasons why everyone should know their annual carbon footprint so that they can reduce their footprint on the environment as much as possible and without delay. In doing so, we quickly see the limits of individual actions and the need for change in our economy.