The terrible floods in Belgium and Germany in the summer of 2021 have left their mark. It is as if Western countries, and more generally those of the North, realised that climatic hazards could also affect them and that no one was safe.

Of course, some people were quick to play down the events and the deaths, saying that “there had always been floods, that it had always happened, and that it had nothing to do with climate change“. Here we go again with a Brandolini Law… Like droughts, hurricanes, mega-fires or heat waves, floods are a complex and multifactorial phenomenon, sometimes underestimated in the collective imagination.

What role has climate change played and will play in floods ? To what extent is soil artificialisation to be taken into account? Is prevention and adaptation up to scratch, especially in France?

To answer this question, we received the help of Florence Habets, CNRS research director in hydrometeorology, professor at the École normale supérieure (ENS) – PSL.

How to define a flood?

In its Special Report 1.5, the IPCC defines a flood as the “the swelling of a river or other body of water beyond its normal limits or the accumulation of water in areas that are not normally submerged“.This term includes :

- river floods,

- flash floods,

- floods in urban areas,

- storm floods,

- coastal floods,

- glacial lake outflows,

- rising groundwater floods.

Just as there are several types of droughts, so there are several types of floods, but their media coverage differs considerably. Those that have the greatest impact on human settlements, industries or agricultural areas are bound to attract more attention than extreme floods where there is hardly any human presence. This is the same logic as for a heat peak in the middle of the Amazon, and one that would take place in the Paris region…

Characteristics and evolution of floods

For fluvial floods (which are historically the most frequent cases), the extent of the flooding depends on three parameters: the height of the water, the speed of the current and the duration of the flood. These parameters are conditioned by rainfall, but also by the state of the catchment area and the characteristics of the watercourse.

Météo-France says that “Intense rainfall brings a very large amount of water over a short period of time (from one hour to one day). This amount may equal the amount usually received in one month (monthly normal) or in several months. In the South of France, accumulations can exceed 500 mm (1 mm = 1 litre/m2) in 24 hours. For the most violent events, the cumulative total exceeds 100 mm in one hour“.

Ten-year” or “100-year” flood

We also often hear the term “ten-year” or “hundred-year” flood event. The definition is very simple. As the flood of a river is measured by its discharge, if a flood has a one in ten chance of occurring each year, it is said to be decennial. If it has a one in 100 chance of happening every year, then it is said to be centennial. Of course, this is a probability. We could have two ten-year floods in the space of 10 years, or even in only 5… The notion of stationarity that implies these probabilities is totally shattered by climate change!

Because this is a complex subject, here are some key points and/or misconceptions to keep in mind.

Firstly, a major rainfall event will not necessarily result in flooding! This will depend on the geography, urbanisation, soil conditions (humidity…), etc. For example, a torrential downpour does not have the same configuration in the Drôme as in Reunion Island (a completely different world!).

Secondly, it is not relevant to compare floods on the basis of death tolls (more on this later). Comparisons that take into account only the cost of damage caused should also be treated with caution. Not only can the damage of a flood vary according to multiple factors (including adaptation and resilience), but estimating it can sometimes take several years!

Finally, we see a trend emerging over the years. Rainfall flooding is becoming more and more frequent, not least because of climate change. What happened in New York in early September 2021 (aftermath of Hurricane Ida) is a very good example: torrential rains and deadly rain flooding, unrelated to river flooding.

New York is flooding again pic.twitter.com/4zX1dfoFU4

— Dr. Lucky Tran (@luckytran) September 2, 2021

No one is safe from floods

The previous video of the New York underground is a reflection of the three months of the summer of 2021: a chain of climate disasters, with global warming currently only +1.1°C. It would seem, however, that certain events have had a slightly greater impact on public opinion in Western countries. After the heat dome in Canada, it was the floods in Germany, Belgium, Luxembourg and New York that made their mark. As if some people realised that climate change is not just for the poorest countries, those furthest away from us. On the contrary: no one is safe, including the industrialised countries.

Asian countries are not to be outdone. On 14 August, Japan experienced unprecedented rainfall in some areas, leading to deadly floods (just like in the summer of 2020). 1.8 million Japanese were still asked to leave their homes after the rainfall… On 21 July in Zhengzhou (China), it rained 200mm in 1H. as a comparison, it rains about 650mm per year in Zhengzhou, just like in Paris…

And always the same people who suffer…

Since we are talking about climate extremes, it is essential to remember that it is the poorest people who suffer first. This is documented in the scientific literature (e.g. by IPCC Group 2) and unfortunately we see it with every disaster. During the heat dome in Canada, it was those without air conditioning who suffered most, and/or eventually died. The same goes for floods. In Belgium and Germany, people living in ground floor flats were most affected.

The same thing happened in New York with the basement apartments (located on the ground floor), or simply unsanitary premises in the basements of buildings. The majority of the (at least) 45 dead are inhabitants of this category. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez had to remind people ‘not to ask for home delivery‘ at the height of the storm, as some people did not understand that it was dangerous for a guy on a bike to deliver their uberEATS in the middle of a storm…

These floods should no longer be considered ‘unlikely’. It is no coincidence that we are entering an era of more and more intense climate hazards, and climate change is one of the causes.

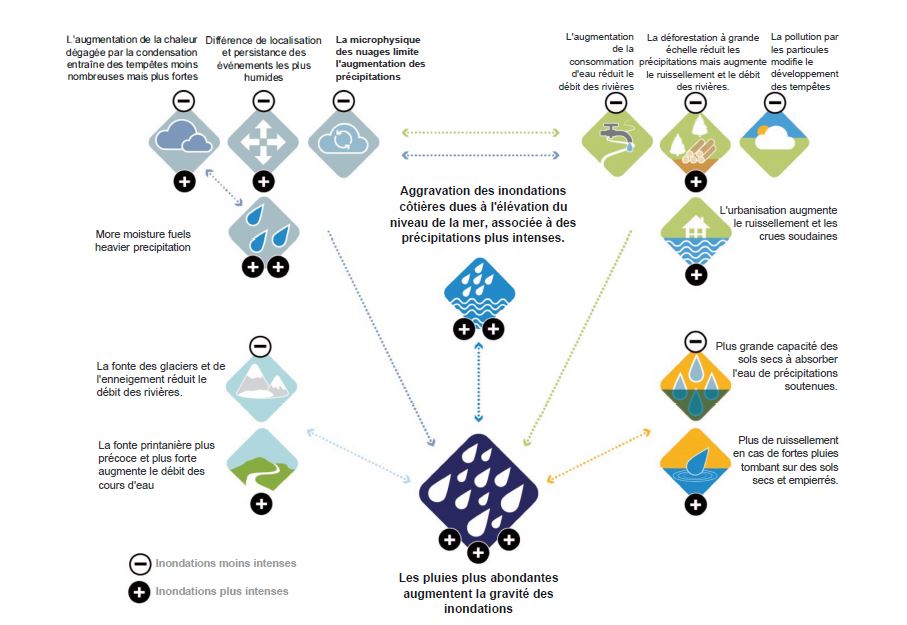

Climate change worsens floods

In case there was any doubt, the conclusions of the IPCC Group 1 report released on 9 August are very clear about flooding and climate change:

- The frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events have increased since the 1950s over most land areas for which there is sufficient observational data for trend analysis (high confidence). Human-induced climate change is probably the main factor.

- Human-induced climate change is already affecting many extreme weather and climate events in all regions of the world. Note that the location and frequency of these events depend on expected changes in regional atmospheric circulation, including monsoons and mid-latitude storm tracks.

- Evidence of changes in extreme events such as heat waves, heavy precipitation, droughts and tropical cyclones, and in particular their attribution to human influence, has increased since the Fifth Assessment Report.

Translation : @YannWeb

More frequent, more intense and combined floods

The IPCC has made a number of important conclusions about future climate hazards.As warming continues, each region could experience more extreme weather events, sometimes in combination, with multiple consequences. This is more likely to happen with +2°C warming than 1.5°C (and even more so with additional warming levels). Translate ‘combined’ as ‘several at the same time or in a row’. It is not uncommon, for example, to see a drought followed by a flood. Another example might be Hurricane Ida, followed by torrential rains in New York: two climatic hazards that come one after the other, the first causing the second.

We also know that therelative rise in sea level contributes to increased frequency and severity of coastal flooding in low-lying areas and to coastal erosion along most sandy coasts (high confidence). With global warming, we are seeing and will see more frequent and more intense flooding, with varying degrees of intensity (with a degree of confidence in each case) by region.

Water cycle and Clausius-Clapeyron relation

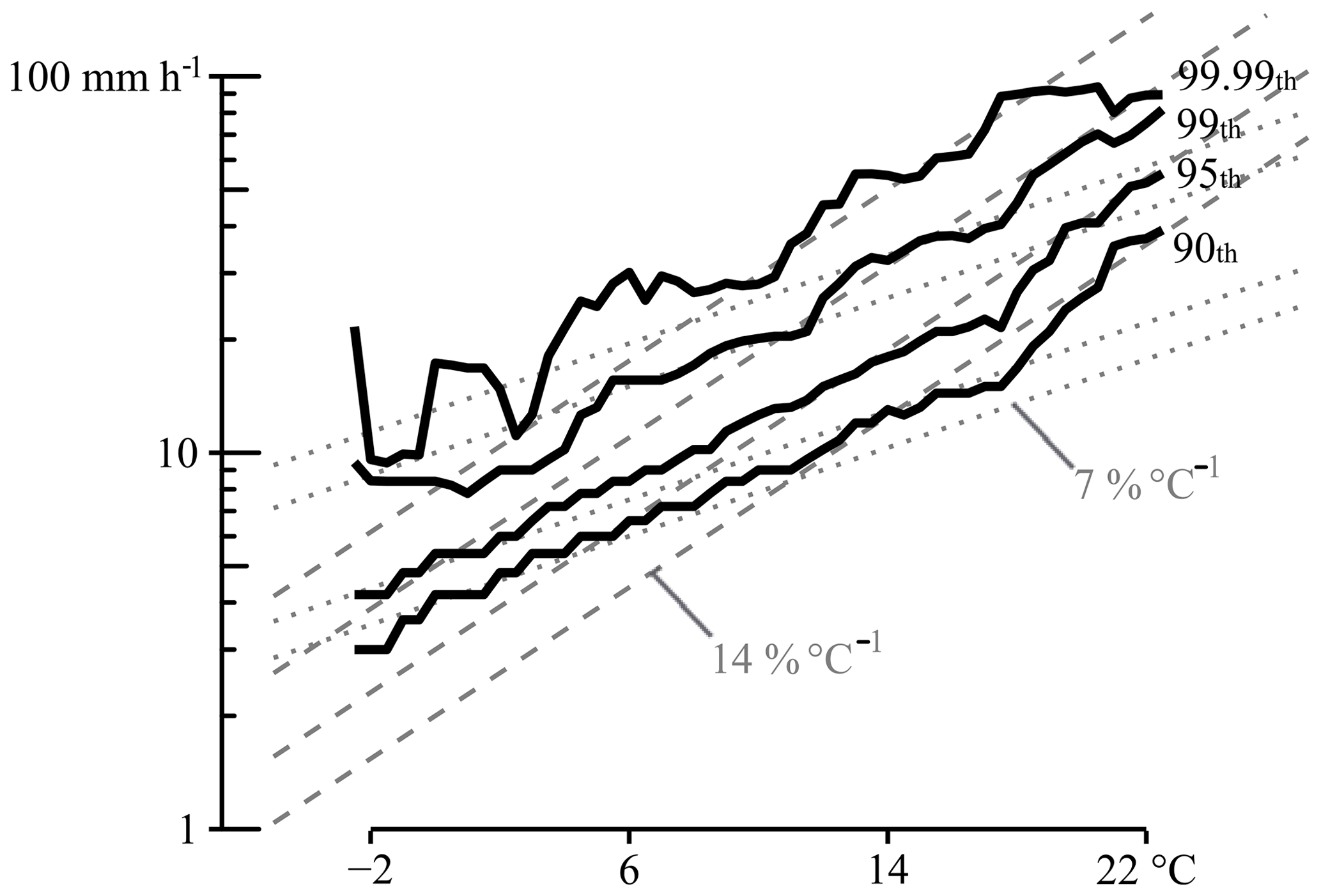

We know that a warmer atmosphere should contain more water vapour, which can fall as rain and sometimes over a short period. The same impact of water vapour in the atmosphere can be seen in storms. A warmer atmosphere carries on average 7% more moisture per degree of warming: this is the Clausius-Clapeyron relation.

It is important to note that this is an average, as on a local scale this 7% can be much higher, due to convective feedbacks from clouds and changes in atmospheric circulation resulting in increased moisture being drawn in by storms. The precipitation in Uccle (Belgium) is a good example of this: the observations showed a 14% increase in the most intense hourly precipitation for each degree increase. This relationship is highlighted in this graph:

Source

Again, and the summer of 2021 is a perfect example to illustrate this, we are seeing more and more pluvial flooding. Hydrologist Emma Haziza recently spoke of a ‘new hydrological era, where runoff dominates land response patterns‘. The water no longer has time to quietly swell the rivers, the sky is falling and the quantities of water that fall form rivers where they meet the ground.

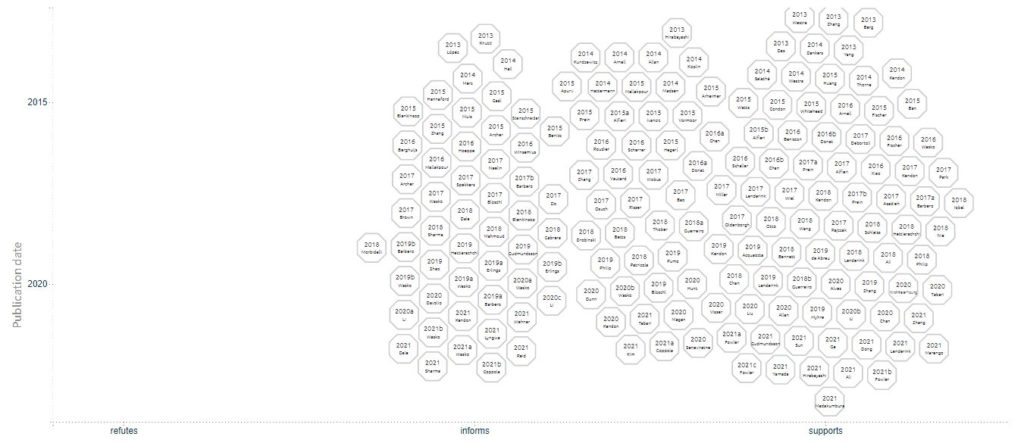

We know that scientists have been warning of these risks for at least 30 years (the 1st IPCC report in 1990 already mentioned them), the scientific literature reduces the uncertainties and the consensus is very clear. For the curious, here is an excellent website where you will find a meta-analysis of 173 scientific papers that show that climate change is increasing extreme precipitation and flood risks:

Source

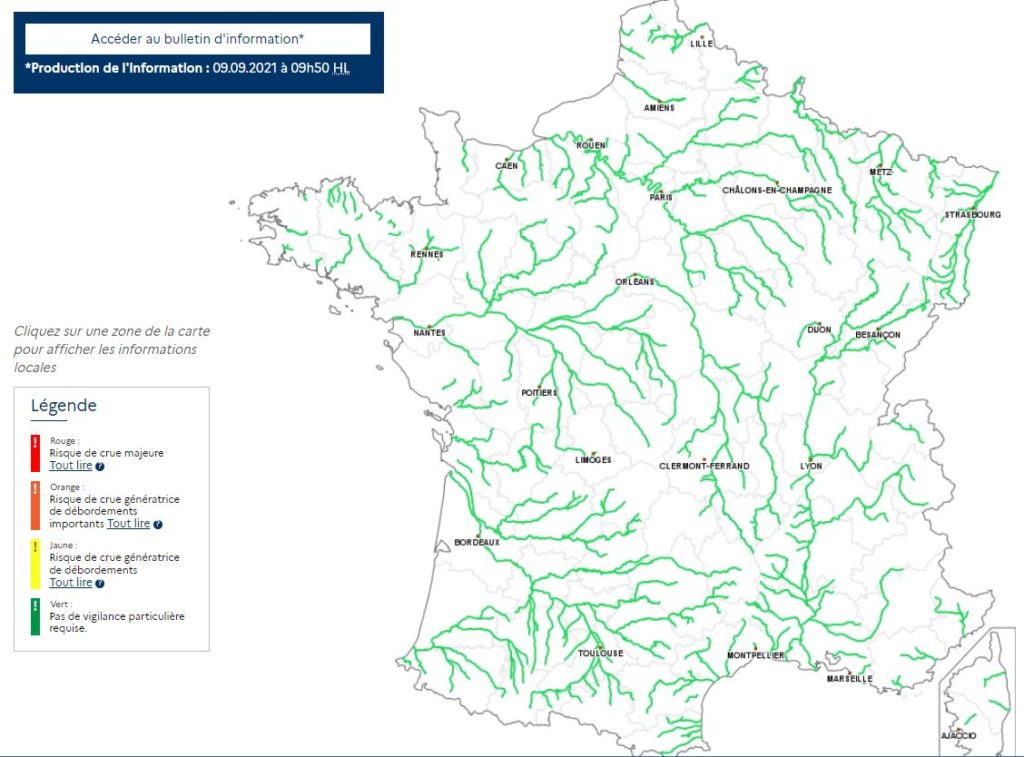

Flood risk management in France

France has a service dedicated to flood forecasting : the SCHAPI. It produces and disseminates continuous flood warning information published on the website www.vigicrues.gouv.fr. It leads and pilots the State’s flood forecasting and hydrometric network (Flood Forecasting Services and Hydrometric Units attached to the DREAL regional services or to the South-East inter-regional management of Météo-France). It is extremely well done, and you can click anywhere on the map to get information on each French region:

This makes it possible to have detailed hydrometric readings, by station, by water level or flow, the latest historical floods, etc. As with other climate hazards, these observation services are very important, as they are responsible for warning of future flood risks.

Not warning people early enough means not being able to warn them so that they can evacuate quickly enough, and ending up with human catastrophes. In addition, in August 2021, the French government set up APIC and Vigicrues flash. These observation-based automatic warning services complement the Vigilance météorologique and Vigicrues (information on hazards in the next 24 hours).

While these stations are extremely important and observation (and human analysis) is fundamental in risk management, and we anticipate increasingly frequent and intense climatic hazards, we could be concerned (to say the least) about budget and staff cuts in the midst of a climate emergency…

NEWSLETTER

Chaque vendredi, recevez un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

+30 000 SONT DÉJÀ INSCRITS

Une alerte pour chaque article mis en ligne, et une lettre hebdo chaque vendredi, avec un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

France is not prepared

It is a mistake to think that floods that will kill and damage hundreds of millions of people are only for exotic, and/or developing countries. At the risk of repeating ourselves: France is poorly prepared for the risk of flooding.

In its annual report 2021, the High Council for the Climate highlights the risks of floods in France:

- Thirty-eight floods occurred between 1964 and 1990, and 103 between 1991 and 2015. Intense rainfall that causes flooding leads to waterlogging of soils, reduced solar radiation and fungal diseases that affect crop yields, as observed in 2016.

- Land use: the attractiveness of coastal areas or certain river valleys explains, for example, the high exposure of housing, infrastructure and businesses to the risk of flooding. These settlements can change in a few decades, depending on demographic or economic dynamics.

- Many childcare facilities (nurseries, schools, colleges) are at risk from flooding. In 2016, for example, 23% of kindergartens in Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur were exposed to the risk of flooding, 42% in the Vaucluse. In 2017, an estimated 20,500 young people were exposed in Bourgogne-Franche-Comté (216 schools and 41 secondary schools).

- The floods in the Tinée and Roya valleys in 2019 have led to the consideration of possible relocations by questioning habitability.

Despite the scientific conclusions of the IPCC and the HCC, caution is required when communicating on a subject as complex as floods, especially when some climate deniers and climate delayers enter the public debate.

Flood and misinformation

One of the main causes of climate inaction is misinformation. Every time there is a climate hazard, you will always hear someone say ‘this is not new, it has always existed, it has nothing to do with climate change‘. It is systematic.

A textbook case occurred in September 2020 with the floods in the Cévennes. Researchers such as Robert Vautard have shown that the intensity of extreme precipitation of “Cevenol events” has increased by about 20% since 1960 due to climate change. Ribes & al. have confirmed this trend.

Mac Lesggy, a well-known TV presenter with 50,000 followers on Twitter, nevertheless declared that there was “no proof that global warming amplifies Cevennes episodes“, before pointing the finger at land artificialisation and urbanisation. Unluckily, several scientists quickly spotted this lie and corrected the facts:

⚡️❌ #FakeNews

— Dr Valérie Masson-Delmotte @valmasdel.bsky.social (@valmasdel) September 21, 2020

Les travaux en sciences du climat @RobertVautard @meteofrance montrent une intensification de ces évènements du fait du réchauffement climatique actuel et futur.https://t.co/X2q5b2EIBQhttps://t.co/XvyoHM3QyDhttps://t.co/FJ25CjP7SLhttps://t.co/9AV0rzXdfZ https://t.co/obm7TObxKi

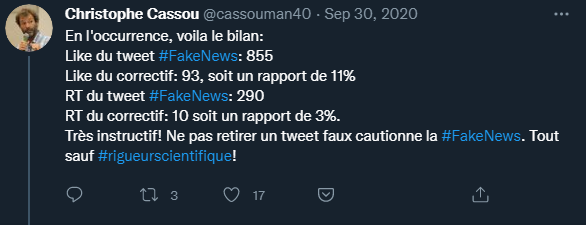

However, this statement provoked 800 likes, more than 200 retweets … and the circulation of erroneous information to thousands of people who would not check the facts for themselves. The comments are very instructive and show how difficult it is even today to combat the circulation of false information. The correction tweet, published the next day, will have 10 times fewer reactions. 10 days later, C. Cassou published this tweet:

Another argument that often comes up is the famous ‘yes, but fewer people died in this flood than in 1932‘. Comparing flood episodes by comparing the number of deaths makes no sense. The number of deaths depends, in addition to the meteorological parameters, on the infrastructure, the preparedness of the population (prevention and warning), the type of flooding (slow or flash), the time of day or night, and the population density.

The difficulty of the exercise, beyond the observations, is to determine whether a climate hazard has been caused by climate change.

Can we attribute every flood to global warming?

We know that the greenhouse effect accentuates both extremes of the hydrological cycle, and that there will be more episodes of extremely heavy rainfall and more prolonged droughts (cf Clausius-Clapeyron). However, how can we know if an event has happened because of climate change? Floods have occurred in the past and we cannot say that a particular flood is due to global warming.

Nevertheless, we can say that the probability of occurrence of these weather events has increased significantly due to anthropogenic climate change. To approach the attribution of an event, one notion is very important: the return period (average duration during which, statistically, an event of the same intensity recurs). This is always accompanied by its confidence interval, the range of possible values, which quantifies the uncertainty associated with the calculation.

Attribution science

How do scientists know whether an extreme weather event can be attributed to climate change?

The calculation is made alternately in the factual world (including human influence, and therefore more unstable) and in the counterfactual world (without human disturbance of the climate). The two probabilities obtained are then compared to quantify the importance of the human influence.

The same process is used to assess the impact on intensity, this time with a given probability of occurrence. Finally, climatologists examine the future evolution of this type of event by using climate projections, i.e. simulations covering the future (often the 21st century), by making one or more hypotheses on the evolution of atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases.

Case study : floods in Germany and Belgium

Attribution science has made tremendous progress in recent years. Thanks to this, we no longer have to wait years to find out if an extreme weather event has occurred because of climate change. Now it only takes a few weeks.

Using a precise methodology, the World Weath Attribution (WWA) was able to provide results within a few weeks on the floods that affected Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg from 12 to 15 July 2021.

Scientists analysed how human-induced climate change affected maximum 1- and 2-day precipitation during the summer season (April-September) in two small regions where recent floods were most severe (Ahr-Erft in Germany and the Meuse in Belgium), and elsewhere in a larger geographical area comprising Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands.

The conclusions are as follows:

- Climate change has increased the intensity of maximum daily precipitation during the summer season in this large region by about 3-19% compared to a global climate 1.2°C colder than today. The increase is similar for the two-day event.

- The probability of such an event occurring today compared to a 1.2°C colder climate has increased by a factor of between 1.2 and 9 for the one-day event in the wider region. The increase is again similar for the two-day event.

- In today’s climate, for a given location in this large region, we can expect on average one such event every 400 years.

- They expect such events to occur more frequently than once every 400 years in the greater Western European region.

All the available evidence (physical understanding + observations over a wider area and different regional climate models) gives the WWA researchers great confidence that Human-induced climate change has increased the likelihood and intensity of such an event and that these changes will continue in a rapidly warming climate.

The urgent need to adapt to the risk of flooding

There is an urgent need to act to limit global warming, and for this we have two options. The first is mitigation: reducing our greenhouse gas emissions. This single option may have been valid in 1980, but since we did not do it, we are obliged to activate the 2nd lever: adaptation. It is mandatory, and here is why:

- Studies by insurers show that climate change is responsible for 30-40% of the increase in disaster costs. The rest is related to increased exposure and vulnerability.

- The models carried out by insurers point to an increase of at least 50% in the number of claims by 2050.

- In addition to deaths and injuries, climate risks threaten property and infrastructure (buildings, networks). Businesses and industries that are, for example, on a plateau-like terrain are not at all prepared for storm flooding (major industrial risk with chemicals).

- One French person in four lives in an area subject to flooding from rivers, the sea, groundwater or storms. One out of two municipalities has all or part of its territory exposed.

The (very) good news is that there are solutions and that everyone can do something about it. Instead of trying to build car parks or terraces at all costs, the solution is simple: planting! And to question local elected officials about the risks of soil artificialisation and future climate extremes.

It is essential to change our approach and to integrate the fact that adaptation requires long-term investments and solutions. It may be more expensive in the short term, but the gains will be incomparable in the long term, especially in the event of climatic hazards. Some cities have already taken these risks into account, such as Douai, which “wishes to prepare for climate change“.

In other words, it will take political courage and no longer seeking short-term profit. We have to reduce our emissions and adapt to climate change, we have no choice. The deaths around the world in the summer of 2021 show that talk of punitive ecology makes no sense and is merely a pretext for climate inaction, which is now deadly.

Key points to remember about floods

- A flood is the “swelling of a river or other body of water beyond normal limits or the accumulation of water in areas that are not normally submerged“.

- The extent of storm flooding depends on three parameters: the height of the water, the speed of the current and the duration of the flood.

- No one is safe from floods, not even the industrialised countries. The climate injustice is once again verified, as it is the poorest people who will be most affected by this climate hazard.

- The frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events have increased since the 1950s over most land areas for which there is sufficient observational data for trend analysis (high confidence). Human-induced climate change is probably the main factor.

- We cannot attribute every flood to global warming, but we know that we are seeing and will see more frequent and intense floods.

- A warmer atmosphere can carry on average 7% more moisture per degree of warming.

- France is badly prepared for the risk of flooding. There is an urgent need to adapt to future climate hazards and to follow scientific recommendations. We can no longer rely solely on mitigating our emissions.