A few months ago, I asked Guillaume Martin (mobility consultant at BL évolution) if he was motivated to write a few lines about cycling to be published on Bon Pote. He came back to me with almost 60 pages of content, well-argued, illustrated, and sourced!

To facilitate the reading, we will publish this file in 5 parts, which can be read in a row or independently of each other:

- Part 1:Mobility structures our lives but has a heavy economic, health and ecological impact

- Part 2: Why develop cycling? Making the case for the bicycle

- Part 3: You’re very kind, but my grandmother or my plumber will never ride a bike: stop the preconceived ideas

- Part 4: Cycling is the best way to decarbonize our mobility

- Part 5: Building a bikeable France

Are we ambitious enough? French objectives for active mobility

An ambitious national bicycle plan, strong growth in terms of use

The ambition of the National Bicycle Plan is to increase the modal share (proportion of trips made by bicycle) from 3% to 9% in 2024 and 12% in 2030. This objective seems ambitious on the scale of our mobility transformation. For example, in 10 years, we will have to catch up with the modal share of a country like Germany.

Everywhere in France, the progress of cycling is impressive. The latest figures on home-to-work trips fromINSEE are available for 2018 and show a relative increase of 8% over one year in cycling in France. In major metropolitan areas, cycling is already taking a prominent place where it can reach over 17% modal share in Grenoble or Strasbourg, 14% in Bordeaux…etc.

In order to achieve the objective of 12% of trips made by bicycle throughout France, the scale of the challenge to be met therefore concerns areas outside the metropolitan areas. It is interesting to note that this increase also concerns more rural areas or less densely populated cities such as Shiltigheim (15.3%), La Rochelle (14.3%), and Le Bouscat (10.2%) or Bègles (9.5%). Even if the modal share of bicycles remains low, including in large cities, compared to our Dutch neighbors (27% modal share on average), Danes (18%), and even Germans (12%), the objectives of the Bicycle Plan will be largely achieved in many French cities.

Since COVID-19, the momentum has accelerated even further. According to the association Vélo & Territoires, which monitors the use of bicycle routes equipped with meters, bicycle use increased by +28% between 2019 and 2021 (+30% in urban and suburban areas and +15% in rural areas).

A lack of short-term resources and little long-term ambition

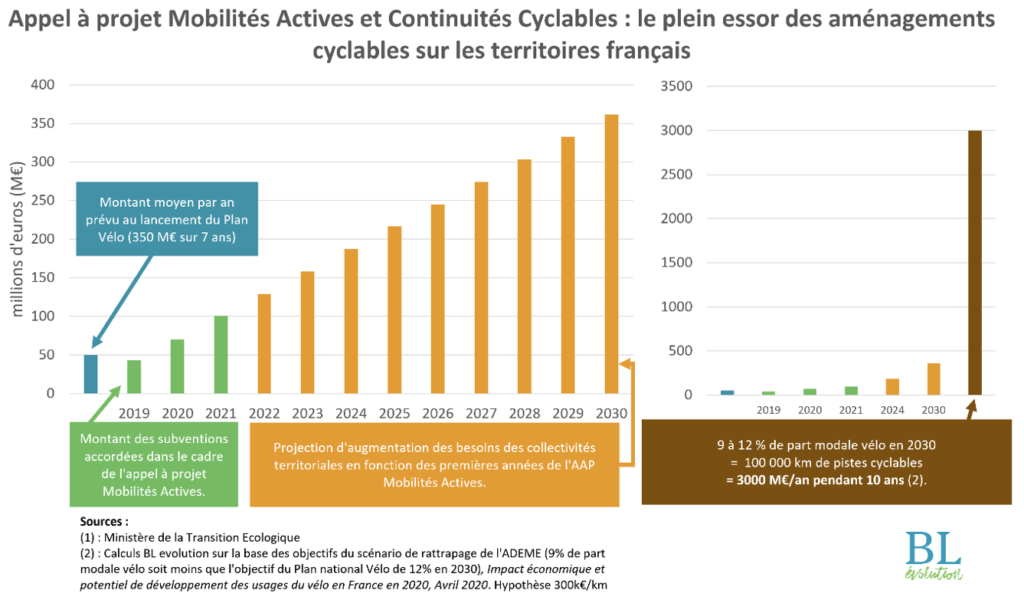

In the short term, we can congratulate the ambition of the National Bicycle Plan’s objective, even if for the moment the means are not available to achieve this objective. A priori, the metropolitan areas have the financial means to act, the cost of the bicycle solution being unbeatable compared to any road or public transport development policy. For other territories, the National Bicycle Plan (about 50 million euros per year for 7 years) has been a real success. The proposal of the Citizens’ Climate Convention was to multiply by 4 the financial efforts (from 50 to 200 million euros per year). Empirically, in the territories accompanied by BL Evolution, the need is often estimated at around 60€/inhabitant/year (we wondered why it was always this order of magnitude, but we did not find an answer). This amount seems coherent with the catching up to be done compared to the Netherlands which has been investing more than 30€/inhab/yr for several decades.

On the scale of the whole of France, this represents about 4 billion euros per year. We can also evaluate this financial need based on the 100,000 km of bicycle facilities to be built and a ratio of €300,000 per kilometer (which is an acceptable average ratio, even if this amount can vary depending on the context). We end up with 3 billion euros per year. All this seems coherent but much higher than the means available to the communities. We can nevertheless assume that some funding will not come solely from the State (departments, regions, or even local territories that can co-finance), but we can see that an order of magnitude is missing in order to meet the challenges.

The National Low Carbon Strategy strongly underestimates the potential of cycling

In the longer term, it is questionable whether France has fully grasped the potential of cycling for mobility. While we have seen (part 4) that many trips can be made by bicycle, including in rural areas, the National Low Carbon Strategy limits itself to a 15% modal share of cycling in 2050, whereas the National Bicycle Plan only plans to increase this share from 3% to 12% by 2030. This means that the rate of development of cycling after 2024 will have to slow down considerably (and increase by barely 3% in 20 years). The total potential of cycling is not unlimited, but some countries already have modal shares well above 20% (e.g., the Netherlands 27%).

Moreover, just as the Electrically Assisted Bicycle or cycle logistics are radically changing the image of the bicycle and its social acceptance, other adaptations inspired by the bicycle are still emerging and have the power to disrupt the landscape of our mobility in a context where carbon neutrality should radically transform our lifestyles and the ways we travel.

The potential of sobriety and cycling to decarbonize our mobility is not taken seriously

In reality, in its SNBC, France is betting much more on hypothetical technological progress than on reducing the demand for mobility (distances) or on the modal shift from car to bicycle. In fact, the opposite is true: the SNBC2 forecasts that the number of kilometers traveled will increase by 26%! The The High Council for the Climate(HCC) has pointed out these shortcomings. In the transport sector, gains in energy efficiency and in the carbon content of energy have barely offset the increase in distances traveled since 1990. As in other sectors, it is politically easier to use a techno-solutionist speech than to try to propose (sometimes radical) changes in lifestyle and habits.

In the transport sector, the High Council for the Climate has shown that gains in energy efficiency and in the carbon content of energy have barely offset the increase in distances traveled since 1990.

The current trajectory leading to delays in the decline of emissions from the transport sector is the result of the same pattern of thinking for almost 20 years. This suggests that the focuson technology (energy efficiency and decarbonization) is a mistake.

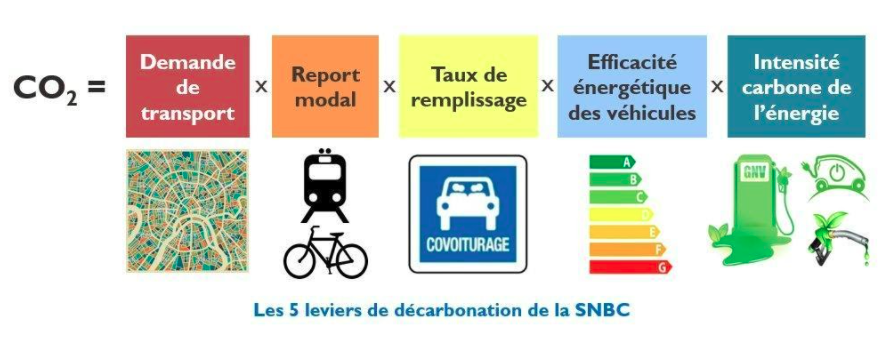

Other works confirm this analysis. In his excellent thesis, the researcher Aurélien Bigo has shown that greenhouse gas emissions linked to transport can be broken down into 5 parameters:

- Demand (the number of kilometers traveled)

- Modal shift (which mode of transport is used)

- Vehicle occupancy rate

- Vehicle fuel efficiency

- The carbon intensity of energy

By comparing the ambitions of several scenarios, including the National Low Carbon Strategy (SNBC), Aurélien Bigo shows that the SNBC relies too much on technological effects to the detriment of sobriety (such as the modal shift toward cycling). It would be too difficult to summarize this excellent work of analysis but I invite you to read his thesis or to watch the presentation of his defense.

In short, France is betting that by replacing internal combustion engine vehicles with electric cars, it will succeed in reaching its objectives for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The reality of the figures shows that as long as we do not change our way of thinking and organization (currently that of the all-car system), the distances to be traveled are likely to continue to increase and therefore, in fine, to compensate for the reduction in emissionslinked to technological innovations or to the electrification of vehicles.

Is the bicycle the enemy of the car? Yes to the opposition of modes!

At this stage of the 5th article, some people might think that for a pro-bike article, many of the arguments are mainly against the car.. Is the bicycle the enemy of the car? Is the car the enemy of the bicycle? These are questions that deserve to be asked. In particular, because we find in many political speeches the famous “let’s stop opposing modes” which, under the guise of appeasement between users, is, as we shall see, above all a speech that favors motorized vehicles.

First of all, let us remember that if modes can be opposed, there is no reason to oppose users. A cyclist can also be a car driver and vice versa. Each user can switch modes of transport according to his or her possibilities and different incentives. Initially, regardless of our preferred mode of transport, we are all pedestrians.

Unfortunately, the grounds for peace between modes end here.

The first argument is that the modes are opposed in the amount of time we spend on them. We saw earlier that even if travel modes change, the number and duration of trips are constant (between 3 and 4 trips and 1 to 3 hours per day per person). So at our individual scale, when we take a car to work, we will not take a bicycle. This may seem logical and completely trivial, but it allows us to understand that work is one of the primary reasons for travel and tends to structure all our mobility habits. Having this in mind also helps to understand why the car remains the preferred mode in many cases. As long as it is quicker to take a private car, we will systematically tend to favor this mode of transportation.

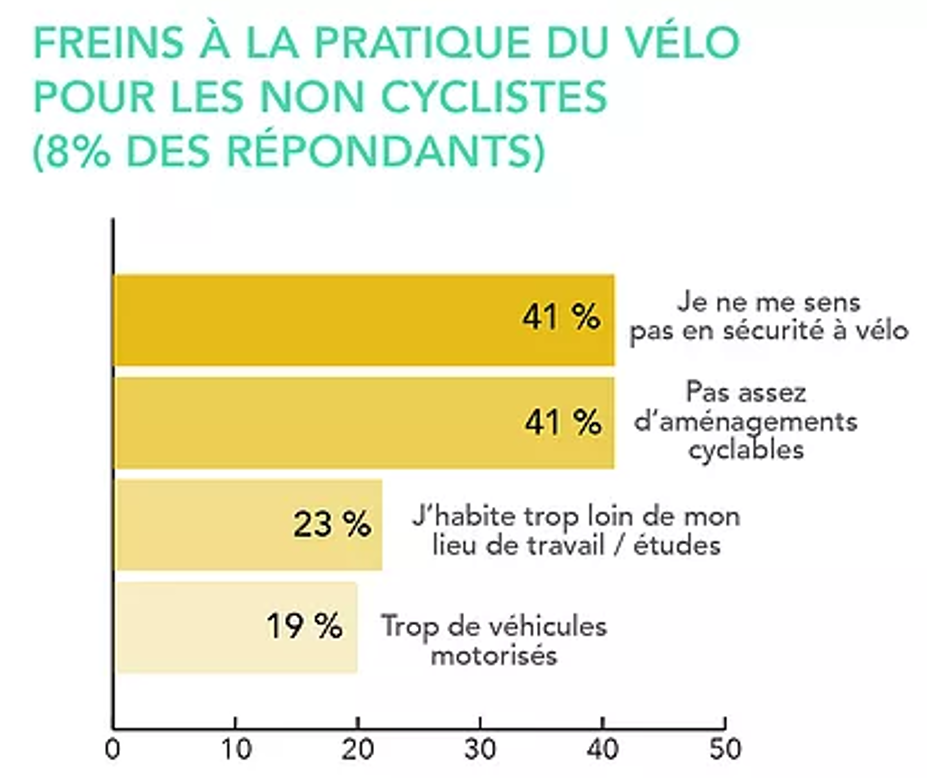

The second argument is that the modes are in conflict with each other in the sharing of public space. As we have begun to see, one of the first challenges in developing bicycle use is to make cyclists’ journeys safe. The lack of safety on a bicycle is the first obstacle to bicycle use in all the surveys conducted so far.

There is no secret that making cycling safer requires a rebalancing of public space. The one thing that all areas that are seeing an increase in daily cycling have in common is that the number and quality of cycling facilities are increasing. In most French cities, 80% of public space is reserved for motorized vehicles. Some people may say that the road is open to all, but I invite these people to take their bicycles on the Place de la Concorde in Paris or on any busy departmental road anywhere in France. In fact, motorized vehicles, when they are too numerous or too fast (as we saw in part 2), exclude other forms of mobility. It is not a question of behavior but of volume and speed, which put too much stress on vulnerable users (pedestrians and bicycles) to allow the development of these modes of travel. A rebalancing is therefore necessary unless we agree to reduce pedestrian space or vegetation in the city (which would not be very consistent with the challenges of the century).

The last argument for the opposition of the modes is that the community’s development budget is limited. Here again, the modes are opposed in the sharing of this budget: the money that will finance a road bypass will not be used to finance bicycle facilities. The evolution seems to be in favor of cycling: since the last departmental elections, Ille-et-Vilaine has chosen to drastically reduce its budget for the construction of new roads in order to finance more cycling facilities.

The difficulty of a good mobility policy is to allow everyone to choose their mode of travel and encourage them to use the mode that is most beneficial to society. The difficulties begin when freedom of use of one mode (e.g., bicycles) requires some constraint on the mode most present in public space: motor vehicles. To oppose modes is to encourage one mode over another, hoping to get users to change their habits as much as possible. All the rhetoric that claims to reject this opposition is in fact a cover for the status quo.

And the status quo is not desirable. As an individual, the car is certainly the best mode of transport (flexibility, speed, comfort…). There are relevant minority uses that justify the inconvenience to the majority (e.g., emergency services or the use of some disabled people), but these do not constitute the bulk of current traffic. On a collective scale, the individual car for all is a utopia. It is already a hell in the city (space, noise, air and noise pollution, road safety…), it is far from being simple and without impacts in rural areas, and on a global scale, it leads us straight to a climate catastrophe.

NEWSLETTER

Chaque vendredi, recevez un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

+30 000 SONT DÉJÀ INSCRITS

Une alerte pour chaque article mis en ligne, et une lettre hebdo chaque vendredi, avec un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

The actors, their roles, and the bicycle ecosystem

In order to develop bicycle use, we must first deconstruct the system that has allowed us to build a society organized around the car. The car has relied on a coherent set of actors, standards, and facilities to develop: construction and maintenance of roads, construction, and maintenance of vehicles, rental services, points of sale, parking, traffic regulations, etc. The development of bicycle use relies on the construction of a similar ecosystem, which implies a restoration of the balance of power between the car and the bicycle. One of the difficulties we are encountering today is that this ecosystem involves a multitude of actors:

- The State sets the ambition of the bicycle plan, the dimensioning of public funding (through a whole administrative universe that does not simplify things), traffic or development rules…

- The regions are in charge of structuring bicycle routes, particularly from a touristic point of view, via the Master Plan for Bicycle Routes and Greenways. They can finance services and activities as well as infrastructure. They are in charge of transportation and therefore intermodality issues.

- The departments manage all the departmental roads, basically all the road development apart from the town entrance and exit signs. They still have a very road culture inherited from the last 50 years but some of them are starting to make their revolution!

- The EPCI = Etablissements Publics de Coopération Intercommunale (agglomerations or communities of communes) which are in charge of planning developments at the territorial level and between communes. It is also at this level that activities are developed (cycling in schools) and incentives such as aid for the purchase of bicycles or rental services.

- Municipalities, which develop city centers, decide on traffic plans, etc.

- Companies and employers who can facilitate access or parking for bicycles in their companies, encourage their employees to leave their cars in the garage via the sustainable mobility package or, on the contrary, offer free car parking to all employees.

- Companies in the bicycle industry, develop essential products and services (sales, rentals, repairs, parking).

- The planners: design offices, private or public architectural firms that design our public space based on the regulations and recommendations in force as well as their own technical culture or vision of the world. We do not design public space today as we have done since Pompidou, and fortunately, there is still a lot to be done at this level!

- Some large groups, which are not directly connected to cycling, such as the SNCF (French National Railways), may decide to put bicycle spaces in trains or to equip stations with secure bicycle parking systems…

- The lobbies, whether they are pro-car (automobile industry, 40M motorists) or pro-bike (Fédération des Usagers de la bicyclette, Paris En Selle…): all the regulatory advances of the last few years are the result of a balance of power in which these actors must not be overlooked…

- The media and the advertisers who, until a few months/years ago, described the bicycle as a leisure machine, whereas today, the front pages of the press on the commuter bike are multiplying.

- Households and public opinion will make this or that planning decision simple and logical or, on the contrary, will cause an unprecedented outcry when it is proposed to remove car parking in order to build a cycle path to the school.

Obviously, all these actors influence each other: they constitute a system. For the whole system to develop, the planets must align and all the actors must make their “bikevolution”.

Some proposals for an ambitious cycling policy

Many changes are already perceptible: everywhere in France, bicycle use is exploding. For a long time a sport or leisure object, the bicycle is now becoming a real tool for daily mobility. This is the time to accelerate the urban, political, economic, and cultural transformations that were beginning to be seen before the health crisis and that has been reinforced since. To do this, here are some concrete and free proposals.

Put pressure on our local policy-makers

The balance of the public space is a history of balance of power. For 70 years, this balance of power in favor of motorized vehicles has pushed our public decision-makers to develop more and more spaces for cars to the detriment of pedestrians, cyclists, or natural spaces. As citizens, we all have a role to play in this balance of power. If the situation has been reversed in the Netherlands, it is because citizens have taken up this issue since the 1970s. It is very well explained in this video or in the magnificent film Together We Cycle. In France, we are living the same movement, as explained in the book “Pourquoi pas le vélo?” Many associations have been formed to question our policy-makers. We must demand a rebalancing of public space and cycling facilities. If you are convinced that cycling should be developed, I invite you to join one of these associations (such as the Paris en Selle association).

Develop a bicycle transit network of 100,000 km of safe, high-capacity, high-quality bicycle paths

This is the number one priority because the main obstacle to the development of cycling is the lack of safety. These facilities must be continuous (safe crossings, continuity between the various facilities), wide and comfortable (e.g. no sidewalk to cross). The CEREMA (a semi-public institution in charge of providing development recommendations to local authorities) has recently updated its cycling development doctrine. Little by little, the culture of bicycle development is progressing and is approaching the best in Europe (particularly the Netherlands). 100,000 km of bicycle facilities may seem like a lot, but let’s not forget that there is more than one million km of roadways. With 100,000 km of bicycle facilities, France would have a network linking most of the municipalities and meeting the needs of most daily trips. We already have a National Plan for Bicycle Routes and Greenways. This is a good framework whose primary purpose is to meet the challenges of tourism. Its implementation deserves to be accelerated, but a wide-ranging reflection on everyday itineraries must be deployed in all territories at several levels (Department, Community of Municipalities or Agglomerations, and at the level of cities).

Provide territories with funding that meets the challenges

As we have seen previously, the financial resources available to the territories are insufficient to achieve the objectives of the National Bicycle Plan. Estimated at €5 or €10 per inhabitant per year, these resources must be increased to about €60 per inhabitant per year (about €4 billion per year). For those who think that this may be a lot, let us recall, as we saw in part 2, that the positive health impacts of cycling in France (less than 3% modal share) are estimated at nearly 5.6 billion euros per year. Another way of thinking could be to encourage (or require) local authorities to set aside 15% of their transport budget for active modes, as has recently been done in the United Kingdom.

Develop a secondary local network based on a reduction in traffic speed outside the main roads and in urban areas and town centers

This policy of dedicated bicycle facilities must be accompanied by ageneral calming of public space to encourage more vulnerable modes. The generalization of 30 km/h in cities has many co-benefits (reduction of noise pollution, road safety, etc.) and encourages the use of bicycles. In many urban areas where there is physically no room for separate bicycle facilities from the road, it will also be necessary to think of a traffic plan that limits transit traffic in the heart of the city. In this way, active modes such as cycling and walking will be all the more attractive as they become safer and faster than the car.

Designing public space at the children’s level

As we saw in section 3, the bicycle is a formidable tool for inclusion that can offer the greatest number of people significant mobility, provided that quality facilities are provided and that these facilities are designed for the greatest number of people. One question that all planners and designers of public space should ask themselves is: “Would I let my children cycle here alone?” This is the question that dictates the planning of the Netherlands, where the majority of children go to school on foot or by bicycle, whereas in France, 47% of children go by car.

Developing intermodality with the train

In rural areas, for trips exceeding 10-15 km, synergies must be found with the train or, failing that, with a public transport network where the bicycle provides a local service to and from the bus stop or train station. Bicycle transport on the train is necessary for certain trips (work, leisure, etc.) to enable households to get out of their cars and must be greatly improved. For daily home-to-work trips, a Dutch-style bicycle parking system in stations (arrival and departure stations, if necessary) would be more appropriate and would require massive parking infrastructures that are far from what we have today.

Do not neglect the services and support aspect.

There are more than 35 million bicycles in France for a 3% modal share. Most of them are in a garage because they are out of use or because people don’t know how to use them. Many solutions already exist in our territories (bike schools, bike buses, bike exchanges, mobile repairers, repair workshops, etc.).…). These solutions often need visibility or financial support in order to multiply their action. Some also require legal or administrative changes. For example, bicycle rental services are an excellent way to test an electrically assisted bicycle before adopting it. Purchase incentives or the sustainable mobility package are a welcome boost to encourage people to change their daily lives.

Creating an industrial sector around the bicycle

The bicycle market in France is already worth more than 2.3 billion euros, is not affected by the crisis, and is a sector already adapted to the challenges of carbon neutrality. In 2019, 2.6 million bicycles will be sold, including 3,800,000 electrically assisted bicycles, according to the Union Sport et Cycles. The bicycle industry in France has known glorious times (Lapierre, Mercier, Peugeot…). Today, while more and more bikes are assembled in France, we do not have an industrial sector capable of manufacturing parts from A to Z.

Developing bicycle logistics loops

Wherever possible, bicycle logistics should be encouraged. This is already working in dense urban areas, where several players have taken up the subject. Some innovations are underway in rural areas. Where density does not yet allow for profitability, should we not consider how to remunerate bicycle delivery services for the negative impacts avoided if the same service were provided by their motorized competitors (noise, air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, etc.)?

Provide local authorities with the human resources and autonomy necessary to develop their territory for cycling

The development of 100,000 km of facilities dedicated to cycling requires significant human resources. Today, the National Bicycle Plan provides some funding, but it is clearly not up to the challenge. To give an order of magnitude, it would take about 1 person per 20,000 inhabitants. This person would be responsible for monitoring the development and implementation of a Master Plan for Cycling or a cycling plan (a document for planning the actions of local authorities in terms of cycling), advising municipalities on their cycling facilities (what types of facilities, what materials, etc.), putting together funding applications, monitoring work in the field, advising companies wishing to promote the use of bicycles, etc. The field of intervention is vast!

Building a one-stop-shop for local authorities (financing, engineering, regulations, etc.)

For local authorities wishing to implement bicycle facilities, long hours of research and engineering are required to design the facilities, build a financing file, etc. There are many people to contact, and many local authorities do not implement bicycle facilities because they cannot find financing even though it exists. Others are simply lost when it comes to choosing the width of their bike path. For all of this, could we not imagine a single national office with local relays responsible for supporting local authorities or training the bicycle planners mentioned above?

Build a common culture and expertise at all levels based on the best standards: awareness-raising and training of institutional players

Having the financial means to implement a cycling policy is good. Making the right choices is better. At all levels, in all structures, France lacks a “cycling culture”. Here, a company will install wheel clamps that are not adapted to the security and parking of its employees’ bikes. There, a municipality will choose a stabilized sand material for daily development or, even worse, a cycle track on a sidewalk. Later, the civil engineering company in charge of the work will build a curb too high to be crossed by bike. In the bike store, the salesman, an experienced mountain biker, will be unable to advise you which rain pants to choose to protect your suit. For all these examples and many more,we need to build a “bicycle culture” inspired by highly cycling countries like the Netherlands. These countries have nearly 50 years of experience behind them, so we might as well not repeat their mistakes!

Put active modes (walking, cycling) at the heart of the traffic regulations

Our British neighbors are about to carry out an in-depth reform of the traffic regultions. Objective: to give priority to pedestrians and bicycles over motorized vehicles (for example by encouraging bicycles to ride in the middle of the road). What if we did the same?

Make urban planning documents, commercial and housing projects consistent

Since the transformation of mobility is essentially a matter of supply (of housing, commerce, land use), urban planning documents must supervise and accelerate their mutations in order to encourage the reduction of distances to be traveled, to increase the quotas of bicycle parking in public spaces and in housing, and to completely stop the expansion of peripheral commercial surfaces in order to encourage local commerce…

Put an end to road infrastructure projects

As we have seen, in order for cycling to develop, it will be necessary to oppose the dominant mode a little. France already has more than a million kilometers of roads (and it seems that nearly half of the world’s roundabouts are in France). We will not encourage the French to abandon their cars on a daily basis by building new roads. The construction of new road infrastructures represents an important financial and climatic cost that seems hardly justifiable in a world where we should be less dependent on the car. Not to mention the indirect externalities (noise, road safety, sedentary lifestyle, consumption of raw materials, soil artificialisation, atmospheric pollution, induced greenhouse gas emissions, etc.). The simple maintenance of existing roads is not necessarily compatible with carbon neutrality. Every euro or ton of greenhouse gas invested in a road infrastructure from today is a euro or a ton of greenhouse gas that does not contribute to the necessary transformation of our mobility. This may seem radical and may shock some people, but some countries, such as the Welsh, have already made this choice. Wouldn’t this be the kind of measures we should take if we had understood the climate emergency?

Thanks to Bon Pote for allowing me to publish in his columns and more generally for the excellent work of popularization done on many subjects. A big thank you to all the contributors who allowed me to write this article. Many of them are directly quoted in the different links you have just read. A huge thank you also for the proofreading work done by Stein Van Oosteren and Aurélien Bigo but also for the BL evolution team : Corentin Consigny, Luc Lavielle, Julien Langé…