Thinking that “climate change, it’s for others!” is an optimism bias, as well as a clumsy error. It is indeed likely that France will suffer less than Madagascar or Cambodia. Nevertheless, French people will not be spared from climate change! And we are not ready for it. Or at least, very poorly.

In our series of articles on climate myths, we looked at several climate hazards that will affect France, including droughts, sea-level rise, and heat waves. For more than a decade now, warnings have been multiplying and post-crisis feedbacks show how ill-prepared we are to face the next ones: Irma and Maria hurricanes in 2017, heat waves, wildfires, repeated droughts, or the unusual frost and hail episodes of the past months. So what about the upcoming events?

The floods in June in France are an example. They caused 550 billion euros of damage and 235 000 casualties. Even though this event received the most media attention after the disaster in Nîmes (FR) in 1988, such urban runoff-induced floods are expected to multiply over the coming years as they are neither“mapped nor considered” when“prevention and adaptation of urban buildings would have cost much less and provided sustainable solutions”, recalls Haziza Emma, hydrologist.

It is no coincidence that the High Climate Council (HCC) has placed a strong emphasis on adaptation and called its 2021 annual report “Strengthening Mitigation, Engaging Adaptation“. But, what does it really mean to adapt in France? What is already in place, and why is it not enough?

We respond to this in the present article with the help of Magali Reghezza, geographer and member of the High Council on Climate (HCC).

What can French people expect in the next two decades?

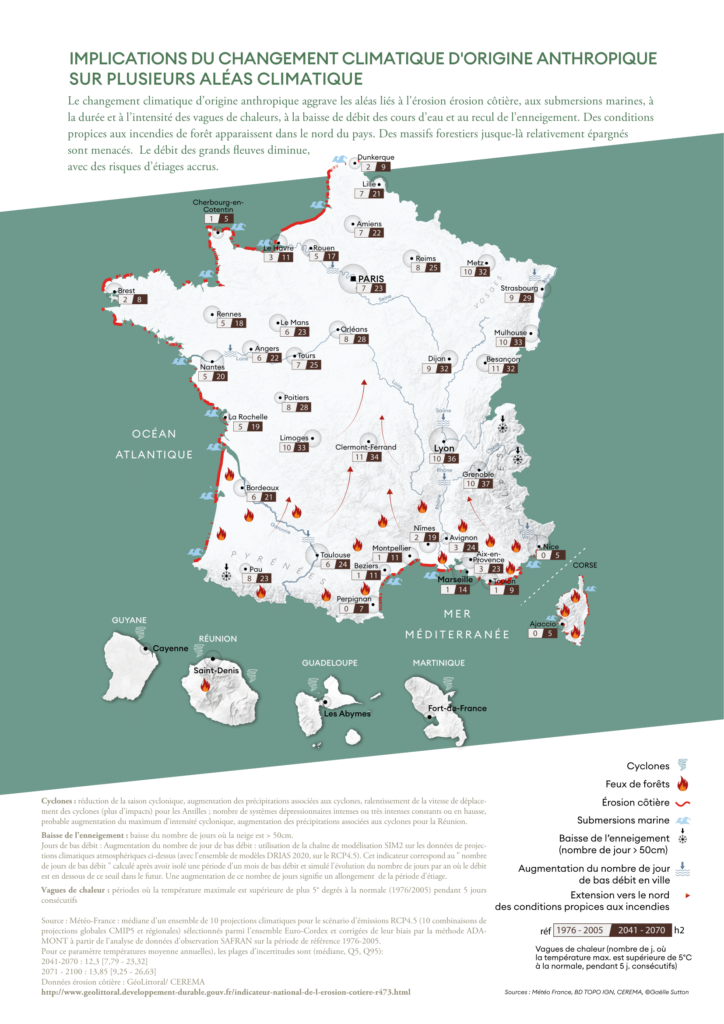

The HCC annual report was based on Météo-France models (DRIAS 2020) to map climate change impacts on the national territory. They used an intermediate scenario (+2.6°C at the end of the century) and looked at the expected consequences for 2040. While the signal is not yet sufficiently clear for precipitation, it is very clear for the increase in average temperatures and extreme temperatures, especially for heat waves. For the record, warming in France reached +1.7°C above pre-industrial levels.

HCC pointed out some key messages:

- A changing climate is an warming trend that is intensifying, with an increase in average temperatures and regional variations. For instance, this implies lower snowfall in the mountains, with a direct impact on tourist activities.

- A changing climate, it’s also more extremes. In particular, more intense and frequent heat waves from May to October. The impact on soil dryness and on conducive climate for wildfires are significant. Fire hazard extends to the northern regions of France, and the fire season extends from spring to autumn, putting a high pressure on emergency services.

- The warming trend could appear beneficial: fewer hail days during winter means less heating and therefore a reduction in fuel and energy consumption. But 2021 has taught us that the threat lies in the interactions between climate changes: as Earth warms, trees will bud earlier in the year at a time when the risk of frost is not yet ruled out. The whole arboricultural sector – including viticulture – is concerned.

- Finally, if the signals are not yet sufficiently robust for precipitation, and therefore certain hydrological extremes such as storms, low water levels, or floods, the attribution studies show that events that would have had no chance of occurring a century ago are becoming possible. As for current extreme events – in relation to the averages – they will become average events.

To illustrate, the 2003 summer which marked France with a deadly heat wave and wildfires will be a “normal” one in 2040. The HCC cites the example of the September 2020 heat wave, which now has an average return period of 12 years, compared to 150 years in the 1900 climate (and would have been 1.5°C cooler), and by 2040 would be three times more likely to occur (with 1°C more).

What impacts, and who will be affected?

When we think of global warming and weather extremes, we of course think of an increase in natural disasters. The models carried out by insurers point to a 50% increase in disasters by 2050. Besides deaths and injuries, climate change-induced disasters threaten properties and infrastructures (buildings, networks). A recent study from the Ministry of Ecological Transition shows that 10.4 billion individual houses will be exposed to shrink-swell clays hazard, which is increased by droughts.

Economical activities will be – and already are – greatly impacted. Agriculture is on the frontline, as it is highly climate-dependent and its impacts on water, soils, and biodiversity. But the industry will not be spared: water-dependent activities are threatened by low water flows (energy production, chemistry, etc.), while equipment and stocks are subject to floods and severe thunderstorms. Tourism is vulnerable to decreasing snowfall as well as the retreat of the coastline. Finally, climate change threatens certain financial assets with induced risks for the economy.

A changing climate is ultimately an everyday life turned upside-down. During extreme heat events, all activities have to stop to ensure the safety of workers. It also means fewer school days, impossible sports activities, postponed exams, and contests. Their impacts on health are significant, especially with more frequent heat waves.

Climate change is certainly not alone to blame, although…

Climate deniers are at liberty to say that these threats already existed. Rivers have always flooded, frost has always destroyed crops, and the coastline is retreating naturally, sometimes with the help of humans, without the need for global change.

Although. Studies conducted by insurers show that climate change is responsible for 30-40% of the increase in disaster costs. The remaining percent is associated with an increase in exposure and vulnerability.

And that’s the whole problem. The climate change hotspot exposure has increased for more than half a century. Today, 62% of French people are already vulnerable to climate hazards. One in four French people lives in an area liable to floods from rivers, the sea, groundwater, or storms. One out of two towns has either all or part of its territory exposed. Despite the prevention policy, the set of protection structures, and the numerous legal tools created in France since the 1995 Barnier law (in particular the risk prevention plans which aim to control the occupation of hotspots), the cost of disasters increases. Combining this with a changing climate, it is clear that action is now urgently required…

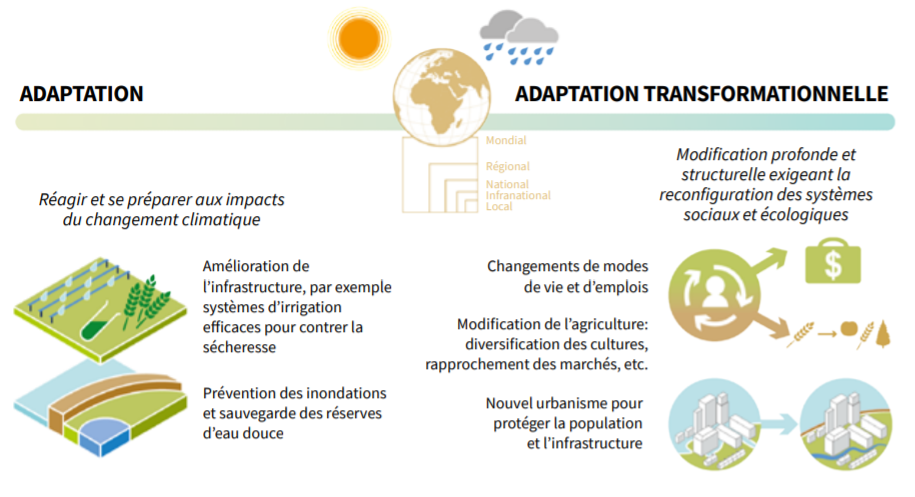

What does it mean to adapt?

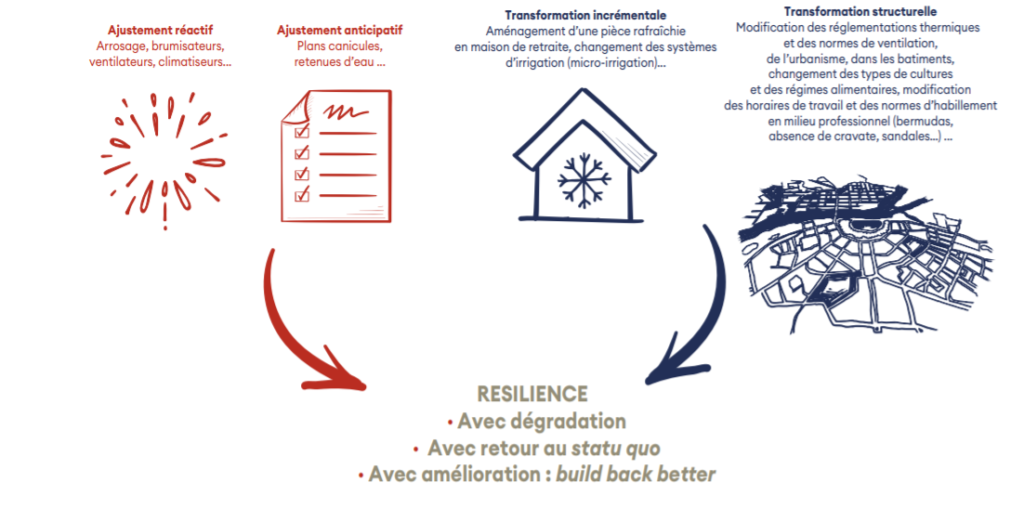

In France, adaptation usually is approached through reactive or anticipatory adjustment. One problem, one solution (if possible, technical); one disaster, a regulatory development. For example, it took dozens of deaths caused by the 2010 Xynthia storm for the flood risk management plan to be created.

We discussed in a previous article that adaptation requires structural changes.

NEWSLETTER

Chaque vendredi, recevez un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

+30 000 SONT DÉJÀ INSCRITS

Une alerte pour chaque article mis en ligne, et une lettre hebdo chaque vendredi, avec un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

Adaptation is at least as essential as Mitigation.

Adaptation efforts will not be the same for a +2°C world or a +4°C one. Therefore, successful adaptation highly depends on successful mitigation. How come?

Because a disaster risk is the result of a three-ingredient combination: the source of the risk (referred as hazard), exposure (which may be direct or indirect) and vulnerability. To paraphrase Jean-Jacques Rousseau in his letter about the 1755 Lisbon earthquake: there is no risk in the desert because there are no houses or crowded people. And if you are invulnerable, you can safely expose yourself to a source of danger.

Mitigation will help to contain the frequency and intensity of hazards. Adaptation is expected to reduce exposure and vulnerability, knowing that certain parameters are beyond our control: population aging, changes in social values, economic crisis, etc. Hazard, vulnerability, and exposure are constantly evolving. Which is one more reason to make a difference where we can.

Poor Mitigation, Poor Adaptation.

If we want to understand the risk, we actually need to add a 4th ingredient: protection against this risk.

Take the dike as an example. A dike is supposed to prevent floods. The dyke will first modify the water flow conditions, and therefore, the hazard. If it breaks or is overtopped, it will cause flash flooding: in 2005, 80% of New Orleans was flooded by breaches in the Lake Ponchartrain levees and the water drainage channels. Moreover, the dyke gives an illusory feeling of safety, which leads to population densification of the supposedly protected areas, and makes the inhabitants forget about the flood risk. That is why we talk about “Dike Risk”.

When misused, the dike becomes an example of “poor adaptation”: although useful in the near term, it turns into a counter-productive measure in the long term. The same might be said for water tanks, snow canons, certain works to combat coastal erosion, etc.

It is also known that, in many cases, mitigation and adaptation go hand in hand. Thermal renovation or agroecology are good examples. But sometimes, mitigation conflicts with adaptation efforts. Expanding cycle paths is fine, but covering them with dark asphalt is a bad idea.

For all these reasons, adaptation itself must be adaptable, and therefore based on diversified and reversible solutions. For this reason, nature-based services (NbS) are becoming increasingly popular.

Good News! We already have a national adaptation plan!

If we look at the glass as half full, France is a good student in terms of adaptation. First, we have a very well-developed disaster prevention and crisis management policy (even if the last few years have shown that there is still a lot of room for improvement…). Then, an adaptation strategy was adopted as early as 2006. We also have a National Observatory on the Effects of Climate Change (ONERC), and, finally, we are in the process of drawing up the second French National Adaptation Plan for Climate Change (PCC)

Yet, already in 2018, a Senate report – the so-called Dantec report – called for a framework law on adaptation. We are far from it. The law “Climate and Resilience” devotes only two articles to Adaptation. As for the second PNACC, it is very insufficient and with no overall strategic vision. The human and financial resources devoted to adaptation remain low. No clear objectives, no set deadlines, no evaluation or feedback on what works (and what doesn’t). There is no national reflection on the land management on the horizon: where will the populations, industrial activities or agricultural production be relocated? How infrastructures will be modified to ensure the transport of goods or people, water and energy transfers? What is the future for ports? Where fire stations will be set up, etc.?

Adaptation is not just an individual matter and cannot just be carried by the territories. While individual actions are essential, repeating over and over that citizens must be responsibilized is a way of shifting the costs of inaction onto individuals. People or companies have not necessarily chosen to expose themselves to risk and insurance companies cannot always pay for everything. And not everyone has the same resources or capacity to adapt. It is always a matter of social justice and a fair share of transition costs.

In this way, it is crucial to implement a real strategy that defines priorities, deadlines, action tools, financial support, compensations, and a fair share of the effort between the different territories and stakeholders.

The last word

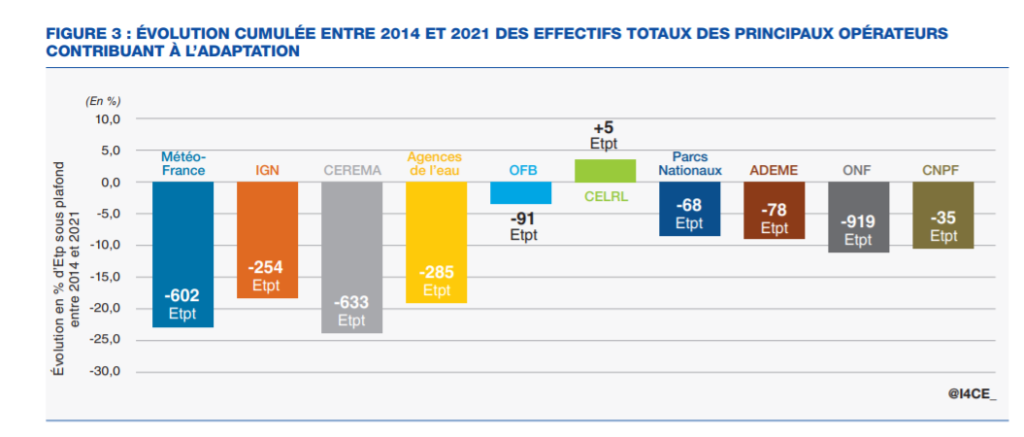

A successful adaptation will require an effort from all actors involved, including the State and public authorities, as well as economic players. In a world where global warming should be the number one priority (as it will affect all areas and increase inequalities), the I4CE has published a more than concerning study where we learn of a decline in the number of employees contributing to adaptation:

At a time when we learn that the workload at the Ministry of Ecology has led several employees to burn out, we cannot hope for miracles if the State doesn’t do everything in its power to support the transition.

Credits sticker: @Sanaga