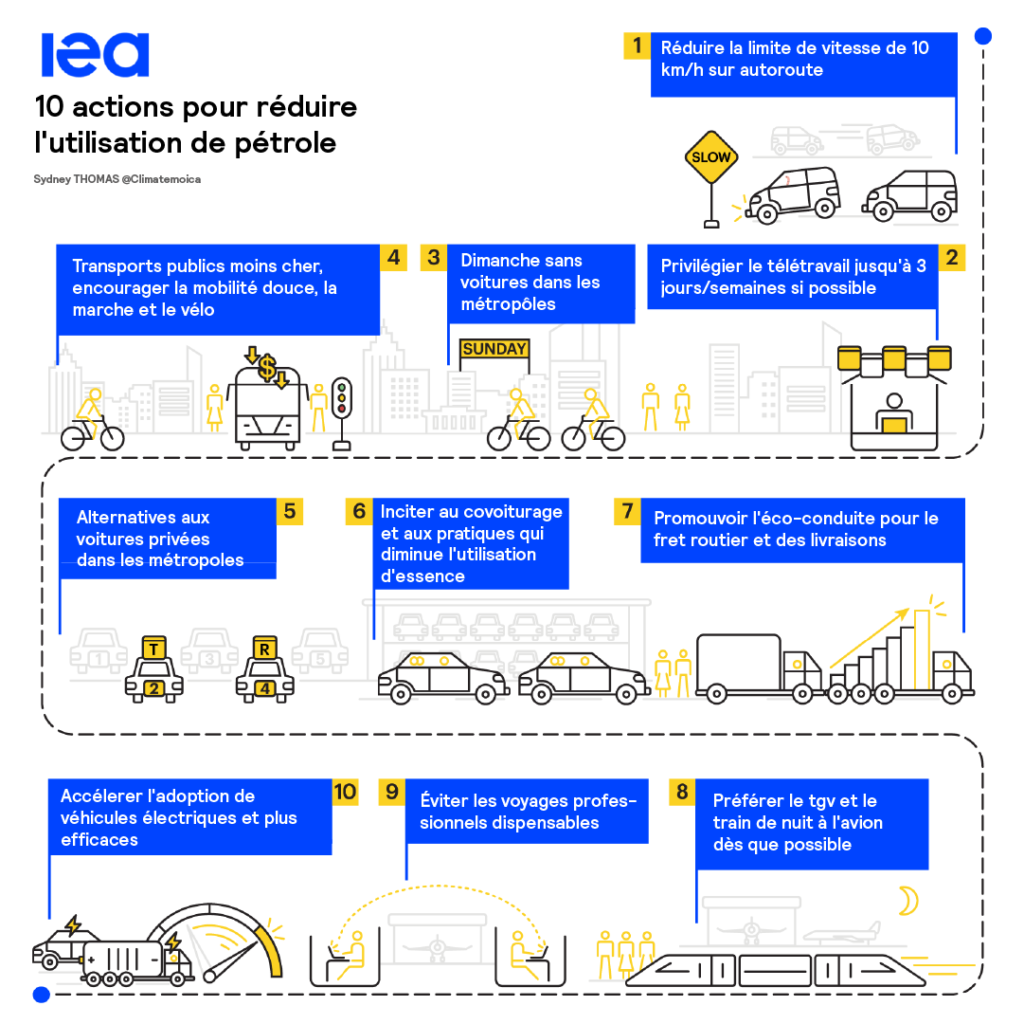

The 110 km/h is back in the debates these last weeks, in a context of urgency to reduce oil consumption. Last but not least, the International Energy Agency has presented the reduction of speed on highways as the first lever to reduce oil consumption in advanced countries [fn] Speed reduction is the first lever cited in the list of 10 recommendations and the second in terms of potential (430 thousand barrels per day, including 290 for cars and 130 for trucks), just behind a proposal that includes carpooling and other practices such as reduced air conditioning and better tire inflation (470 thousand barrels in total) [/fn].

It is all the more interesting that this recommendation comes from an institution that is generally very cautious about using the levers of sobriety in the energy transition.

Source : IEA

To understand why the 110 km/h on highways is often quoted these days, here are 10 reasons why this measure is interesting and deserves to be quickly implemented in the current context (rising oil prices, possible embargo on Russian oil, climate emergency).

1. The 110 km/h, one of the (very) few measures with immediate effects

The current transportation system has been built over many decades by interactions between land use, lifestyles and economic activities that maintain dependence on the private car and oil. This explains the current strong inertia of the system, and the difficulty of achieving rapid changes in the transport transition [fn] The five levers of energy transition in transport cited by the French national low-carbon strategy (SNBC) are: moderation of transport demand, modal shift, improvement of vehicle filling, energy efficiency, and energy decarbonization. There are often significant inertia to achieve significant decreases in oil consumption through the use of these levers, which are also studied in their contribution in the past and by 2050 in the thesis linked above (on the speed of implementation: see Table 21, page 241). [/fn]

The good news is that lowering the speed limit on highways is one of the few measures that have an immediate effect, from the day it is implemented and on a national level!

The interest is therefore particularly strong in a period of geopolitical, social and economic emergency such as the current rise in oil prices and the need to cut off funding to Russian oil. We will see that it is also relevant for the energy transition in the longer term.

2. significant efficiency gains and savings for motorists

The direct impact of reducing the speed on the highway from 130 to 110 km/h corresponds to a fuel saving of 16% per kilometer driven.

These efficiency gains are particularly significant compared to the gains of around 1%/year achieved in recent years by the gradual renewal of the vehicle fleet.

As the measure is not always well received by some motorists, one could almost forget that it allows them to save money! And that these 16% gains for the portions and motorists who would go from 130 to 110 km/h, are far from being negligible for long distance trips.

Unlike a number of other measures that aim to reduce the place of the car or its environmental impacts (carbon tax, tolls, parking costs, etc.), the measure reduces the cost of mobility for car users and therefore does not risk creating fuel poverty in its implementation.

3. incentives to reduce car miles

Beyond the measure’s direct impacts on energy efficiency, there are also positive indirect effects on other decarbonization levers. Starting with the moderation of transport demand and modal shift.

Historically, we have not taken advantage of the acceleration of mobility to reduce our travel times, but rather to go further. The reverse is also true: if we slow down mobility, this provides an incentive to limit the distances travelled.

This phenomenon has already been observed, since the introduction of speed cameras from 2003 onwards has probably had a very significant impact in reducing car traffic over this period [fn] Since speed and travel time are a major determinant of mobility behavior, slowing down limits the potential rebound effect of the measure on miles traveled that might be expected from the savings. This is all the more the case in a context where fuel prices are high and thus limit the risk of a rebound effect.[/fn].

Also, by reducing the speed of the car, it gives an incentive to modal shift to train or bus (limited to 100 km/h), for which it is in comparison very expensive or very difficult to increase the commercial speed. Of course, it is also important to limit air traffic to avoid a shift to this mode.

4. Slowing down to 110 km/h encourages more fuel-efficient vehicles

While speed reduction has direct effects on vehicle energy consumption, it may also have positive indirect effects in the future by encouraging vehicle fuel efficiency.

Indeed, speed feeds certain vicious circles playing on the increase of the weight of vehicles. In particular, because speed requires greater engine power, the weight of these engines increases. Also, higher speeds require greater protection and safety equipment. These weight increases can affect the volume of vehicles and limit their aerodynamics, limiting the fuel efficiency of vehicles. This will require more powerful engines, again feeding the previous vicious circles.

On the contrary, a 110 km/h limit in France would facilitate virtuous circles in the opposite direction, encouraging the production and sale of vehicles that are more economical in terms of weight, power and maximum speed. This would be all the more the case if speed limits were brought to the European level, by integrating incentives for sobriety or standards (such as the maximum speed of vehicles, why sell cars that can drive at 176 km/h?) in the European regulations for new vehicles.

5.it is also relevant for electric vehicles

One might think that there is less interest in electric vehicles, which emit less CO2 in use. And yet, the reduction in energy consumption from 130 to 110 km/h is 24% for electric cars, even more than for the current fleet of thermal vehicles (-16%). Therefore, some of the virtuous circles related to speed reduction, as mentioned above, are also valid for electric vehicles. And reductions in energy consumption can be beneficial in two ways.

Option 1: with equivalent battery capacity, they can increase the range and the number of kilometers covered without recharging. By the way, lesser stops to recharge the vehicle on long trips will eventually allow to avoid recharge times, highlighting a trade-off between traffic speed and break times to limit the total travel time.

Option 2: To maintain the same range, the vehicle can make do with a smaller battery. Given that a significant part of the environmental and financial costs of electric vehicles are on the battery, this is an interesting potential to facilitate a virtuous development of electric vehicles.

NEWSLETTER

Chaque vendredi, recevez un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

+30 000 SONT DÉJÀ INSCRITS

Une alerte pour chaque article mis en ligne, et une lettre hebdo chaque vendredi, avec un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

6. 110 km/h has co-benefits on other transport externalities

Speed reduction also has benefits on other transport externalities (or impacts).

In particular, it is about the reduction of air pollution and noise pollution, the latter being essentially the result of aerodynamic noise at such speeds. It is also a matter of reducing congestion, because the higher the speed to reach a congested area, the more it is reached and reinforced.

Another advantage that we can think about is the accidentology, although the highways are not the most accident-prone roads. This reduction is also part of a global movement to reduce speed on the roads, including the 30 km/hin built-up areas (which could be reinforced at present to make active modes safer) or the recent change to 80 km/h outside built-up areas, a limit that is all the easier to comply with when leaving highways at 110 km/h than at 130 km/h.

While some of these benefits on highways may be partially offset by slightly greater impacts on other networks through route shifts, this would not negate them overall.

7. A more acceptable measure than 80 km/h?

Let us now turn to the main objections to 110 km/h and its acceptability.

Compared to the 80 km/h measure on roads outside built-up areas (two-way, without a central separator, to be precise), the 110 km/h on highways is much less relevant for daily trips, or at least it is for a much smaller fraction of the population.

Also, highways are used more for long-distance trips, vacations or leisure, which are more exceptional and therefore less structuring in daily life. Finally, we know that these long-distance trips are much more important among the most affluent people, so the measure will essentially apply to these households, thus avoiding accusations of social injustice.

This may facilitate the acceptability of the 110 km/h, and probably pushed the Citizens’ Climate Convention to finally retain this proposal after intense debates, barely two years after the implementation of 80 km/h.

8The crisis context makes the measure more acceptable

Despite the above, the acceptability of the measure has been quite limited in recent years, probably in part due to doubts about its environmental benefits. At the end of 2021, the ADEME barometer showed that 42% of the population considered it desirable.

But the context of the war in Ukraine, the resulting urgency to reduce our consumption quickly and the rise in oil prices are certainly changing the situation, making this kind of effort more acceptable. It is not surprising that the speed limits of 90, 110 and 130 km/h on French roads were put in place following the first oil crisis.

In the same way today, there is an urgent need to implement all the measures that make it possible to reduce oil consumption, in particular those that have short-term effects.

Also, these measures must be applied to the whole population and not only to the less fortunate households who will probably already apply for part of the speed reduction, one of the main strategies during the fuel price increases, without strong questioning of the behaviors.

9.weak negative effects on mobility practices

The above indicates that slowing down speeds or eco-driving can naturally be part of coping strategies in the face of rising oil prices, as they imply limited changes in mobility behaviors, for all those who do not have the possibility to move away from oil dependence in a stronger way (by telecommuting, using bicycles, public transport, or switching to electric vehicles).

While the most obvious and strongest effect is the increase in travel time, the impacts become significant only for trips of several hundred kilometers, which are relatively rare (trips of over 80 km are estimated at 1.6% of car trips only).

Thus, while the theoretical effect is an 18% increase in travel time for a given distance (or +8 to 9 minutes per 100 km), in reality travel times are much less impacted, especially if the off-highway portion is high, but also because the current highway speed is 118 km/h on average, that it makes traffic flow more smoothly, that long journeys are also marked by breaks, slowing down, etc. Real-world tests tend to confirm these much smaller than expected impacts on travel times.

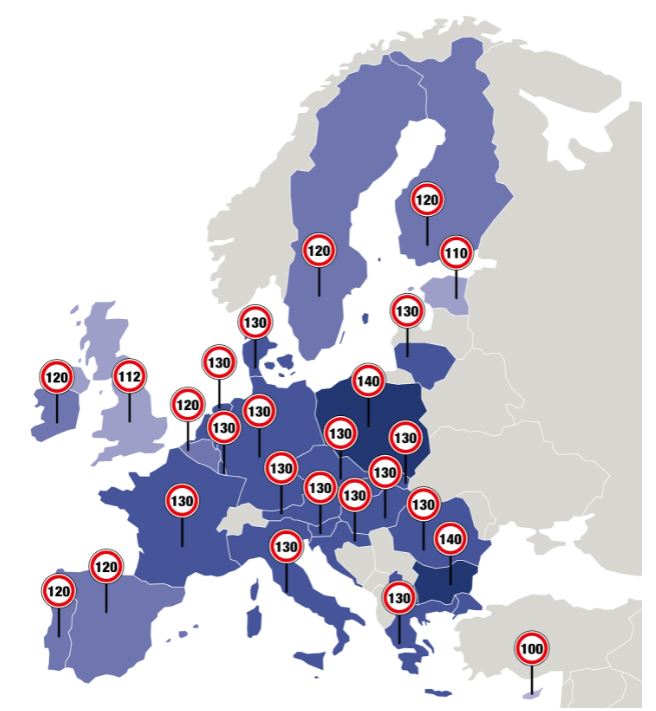

10. many countries below 130 km/h

If the mention of speed limits in other countries generally leads to the particular case of Germany and its highways without speed limits, it is in fact only a part of the network, and the countries which are above 130 km/h are rather exceptions (only Bulgaria and Poland in the EU, which are at 140 km/h).

While many Central European countries also limit their highways to 130 km/h, 9 countries are below this limitThese include Belgium, Spain and Portugal, where networks are limited to 120 km/h, the United Kingdom to 113 km/h (70 mph), and the Netherlands, which recently reduced its speed from 130 to 100 km/h during the day for climatic reasons. Even more surprisingly, highway speeds are also lower in the United States, generally between 105 and 121 km/h (65-75 mph), although there are significant differences between states.

The disparities in Europe could also encourage discussion of reducing the speed limit on highways at the European level. This would maximize the potential for reducing consumption at a time when the whole of Europe is threatened by the consequences of its dependence on oil and faces the common challenge of moving away from Russian oil.

The last word

The 110 km/h on highways will not do everything in the current period [fn] Assessing the impact of the 110 km/h measure is difficult, as it involves many direct and indirect factors, and depends on behavioral adaptation, which is complicated to anticipate. In order not to risk such assumptions, only direct and indirect effects have been cited in this article, without any precise figures. For information, evaluations have estimated gains of the order of 1.5 and 2 MtCO2which is equivalent to approximately 2% of emissions from cars and light commercial vehicles in 2019, a potential that is underestimated, however, because it does not take into account many of the indirect positive effects discussed in this article. Many other measures will of course have to be put in place to meet the challenges of climate change and to get rid of Russian oil, which accounts for 10 to 20% of French imports and 30% at the European level. [/fn]which requires strong actions and consequent efforts from all to reduce oil consumption.

But in the short term, this is probably the best (or least bad) option for significantly reducing oil consumption, while having other positive impacts in the short and long term. It would be incomprehensible to do without it at a time like this.

And to those who would be tempted to cling to this “freedom” to drive at 130 km/h on the highway at all costs: just think of the effort that this evolution (among many others to be implemented) represents, compared to the risks that weigh on our freedoms if we are not up to the current geopolitical challenges or climate change…

Text by Aurélien Bigo, researcher on the energy transition of transport

Notes

Many elements and reflections in this article refer to the thesis work Transport facing the challenge of the energy transition. Explorations between past and future, technology and sobriety, acceleration and slowing down These include decarbonization levers (chapters 1 and 2), their advantages and disadvantages (chapter 4), and the speed of mobility and its implications, which is the subject of chapter 3 (pages 142-221).