It’s basic math: planes emit between 30 and 50 times more CO2 than trains (if you didn’t know that or if you still had a doubt, read this article). However, this calculation does not take into account the CO2 emissions related to rail infrastructure and maintenance. Ah…

So if we wanted to replace all the airlines with high-speed trains, would it be beneficial in terms of emissions? In other words, with the CO2 emissions of domestic flights in France, how many km of high-speed rail (HSR) could we build?

Laydgeur answers this question in this second round!

Railway infrastructures

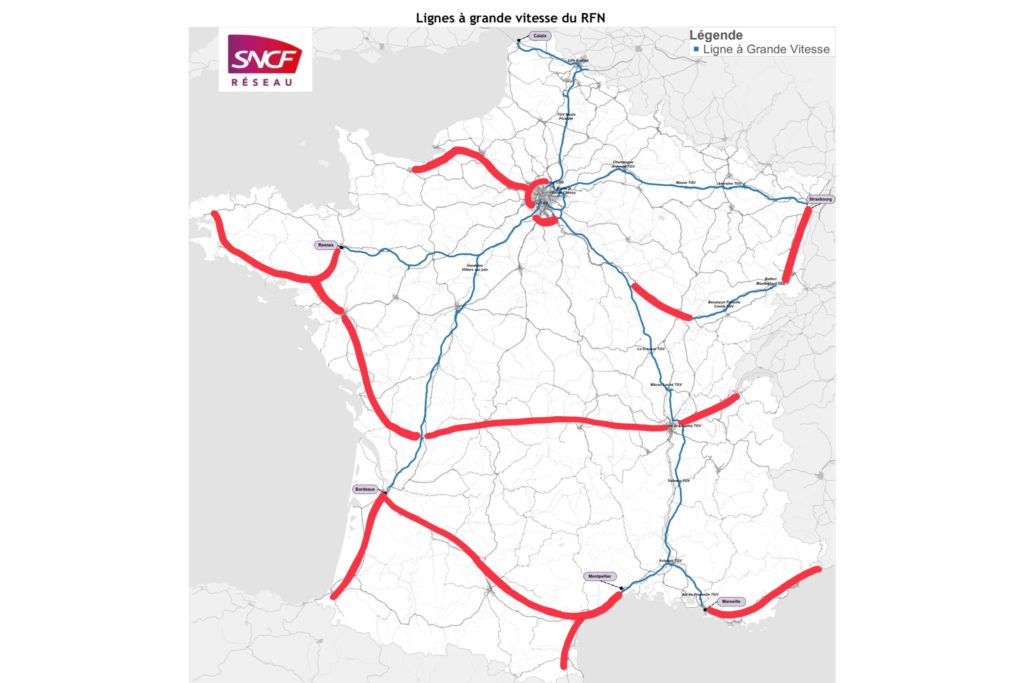

In France, there are 2600 km of HSR, which represent 9% of the total rail network, the first of which was built in the 1980s (Paris-Lyon opened in September 1981).

Source : SNCF Réseau

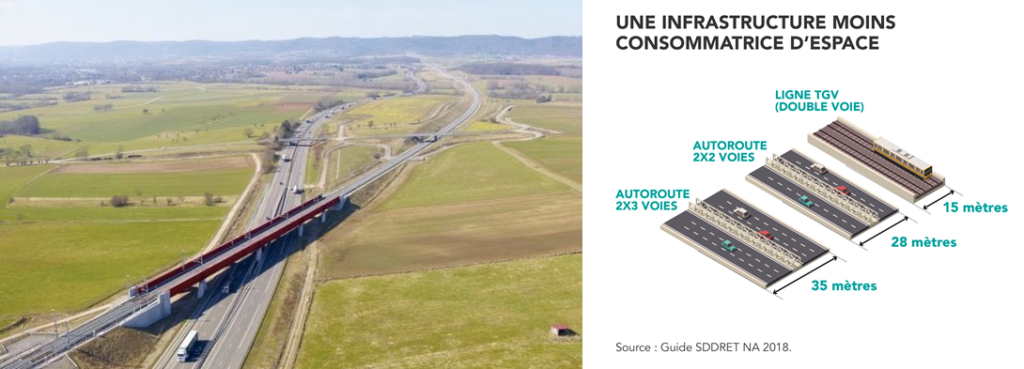

The construction of an HSR is a big project, but not outstanding either. It is, for example, of the same order of magnitude as a motorway:

Right: comparison of motorway and HSR width (Source SNCF Réseau)

How is the carbon footprint of a railway line assessed?

The very first carbon assessment of an HSR was carried out by SNCF Réseau for the 140 km of the eastern branch of the Rhine-Rhone line, which was commissioned in 2011 and roughly links Dijon to Belfort.

Image from Le Figaro

Some figures about this HSR construction project:

- 160 bridges and 13 viaducts

- a 2 km long tunnel

- 30 million m3 of excavated material

- 600 km of rail, 550k crossties

- 2 new and 10 renovated stations… in which 30 new double-decker TGV trains will run. Phew…

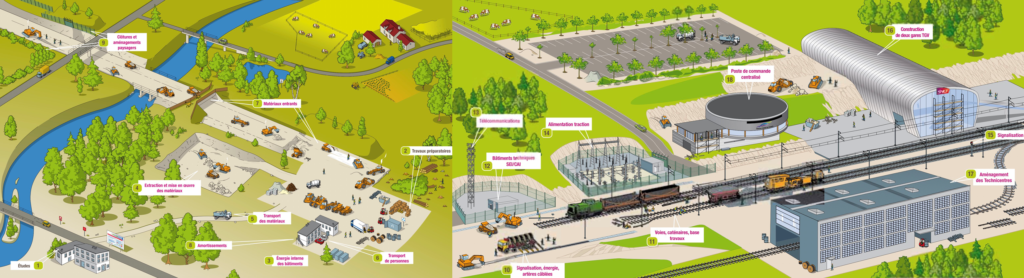

For the carbon footprint assessment of this line, everything was taken into account: deforestation, earthworks, materials, construction equipment, transport (materials and personnel), TGV trains, stations and other buildings, signaling, etc.

The level of detail is quite impressive in its transparency: the computers used for the studies, the commuting of all the site staff, the fences, and the landscaping of the road were also considered.

The assessment did not end with the construction of the line : from a life-cycle analysis perspective, emissions during the operation of the line were also considered: power generation, station operation, maintenance of trains, tracks, and equipment.

Source: bank of territories

So what is the final result?

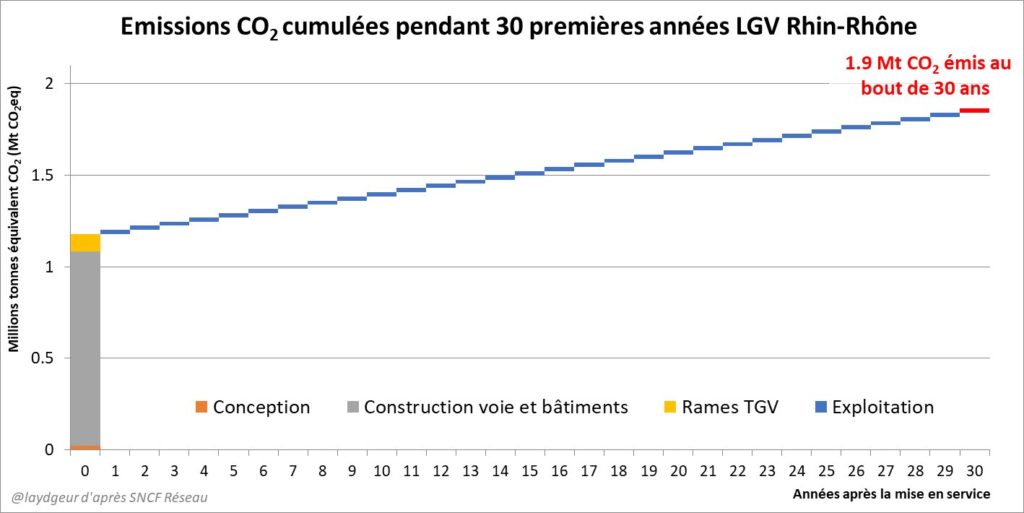

Over the first 30 years, the construction and operation of this line will have emitted almost 2 million tonnes of CO2, broken down as follows:

- 1,2 million tonnes of CO2 from the start of the construction of the line (these emissions are actually spread over the few years from the design to the construction of the line)

- and then 23,000 tonnes of CO2 per year for electricity and maintenance (or 0.7 million tonnes over 30 years).

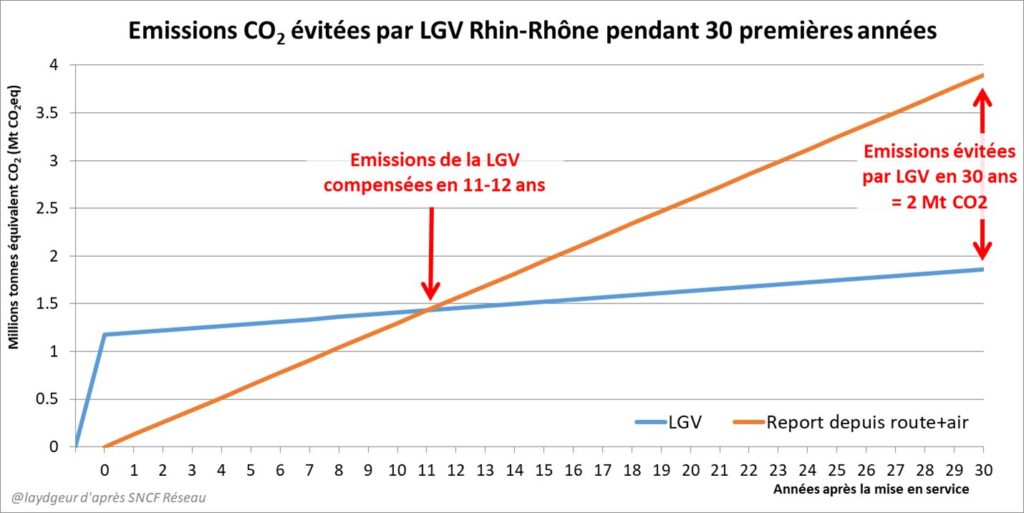

In order to calculate the “carbon efficiency” of this HSR, it is necessary to calculate the CO2 emitted (which has been done with this carbon assessment), but also the CO2 avoided. Indeed, the new line is expected to divert about 1.2 million passengers from the air and road each year (the so-called modal shift), so that its emissions will be “amortized” compared to a situation without the high-speed line in just 12 years.

Everything else will be a net benefit in terms of emissions. After 30 years of operation, the HSR will have avoided about 2 million tonnes of CO2. Considering that the track lifespan is about 100 years, the benefit is clear, even if the modal shift forecasts were overestimated.

It’s exactly like buying an electric car: there are more emissions at the beginning to build the car and its battery (a “carbon debt”) but much less during operation, therefore the whole thing is more carbon-efficient.

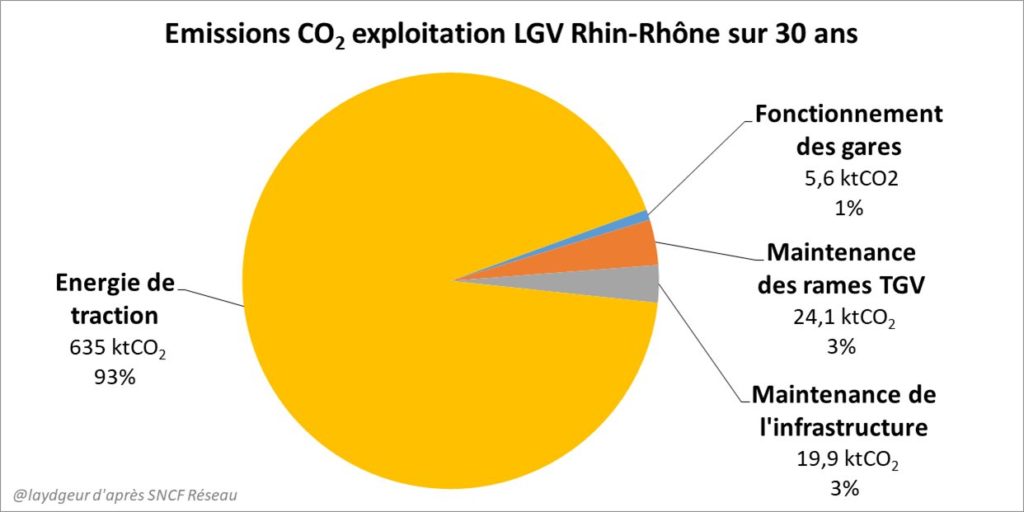

If we consider the operating phase, we can clearly see that CO2 emissions due to maintenance (of trains and infrastructure) are largely in the minority compared to those of electricity production, despite France’s low carbon electricity mix. In other words, almost all the emissions from a high-speed train line come from emissions linked to electricity production, which, despite what one might think, is not totally decarbonized in France (still 19 million tonnes of CO2 emitted in 2019).

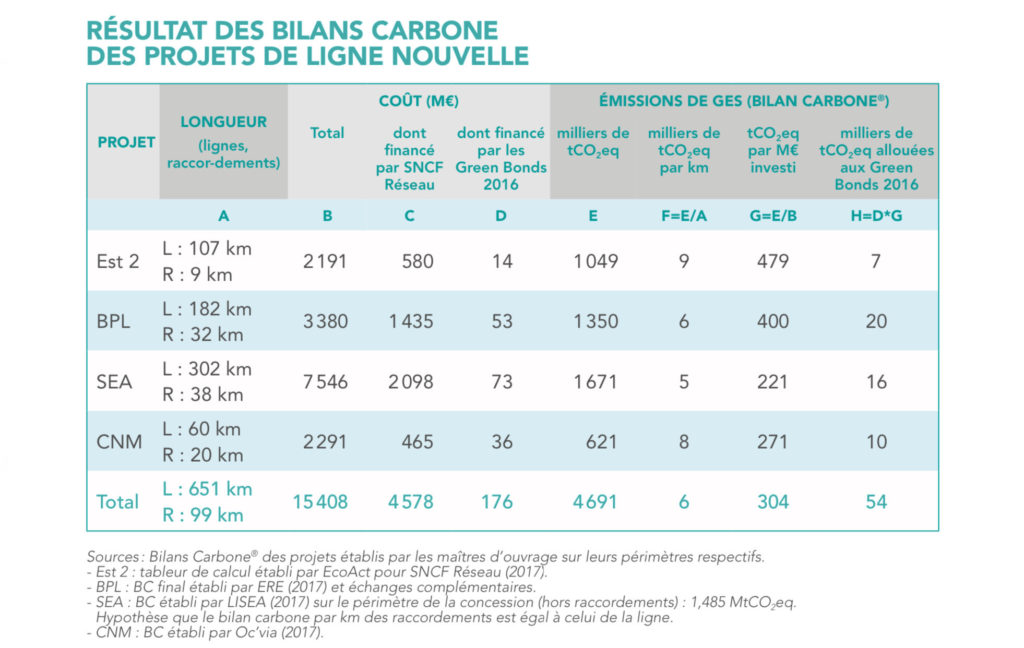

Let’s get back to the focus of this article: the construction of this Rhine-Rhone HSR alone (civil engineering, trains, equipment, and buildings) resulted in the emission of 1.2 million tonnes of CO2. The ratio is therefore 8,300 tons of CO2 per km of HSR, for this line. What about building new lines?

The carbon footprint of building new lines

Other carbon footprint assessments have since been carried out on other new HSR constructions, using the same methodology as above. The average is lower for various reasons: route, structures, materials, etc. The average ratio is about 6,200 tonnes of CO2 per km of HSR. Keep this figure in mind, we will come back to it later.

NEWSLETTER

Chaque vendredi, recevez un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

+30 000 SONT DÉJÀ INSCRITS

Une alerte pour chaque article mis en ligne, et une lettre hebdo chaque vendredi, avec un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

Aviation carbon footprint in France

Emissions from domestic flights are just over 5 million tonnes of CO2 per year (or just under 1% of French emissions). Except that… there is a subtlety.

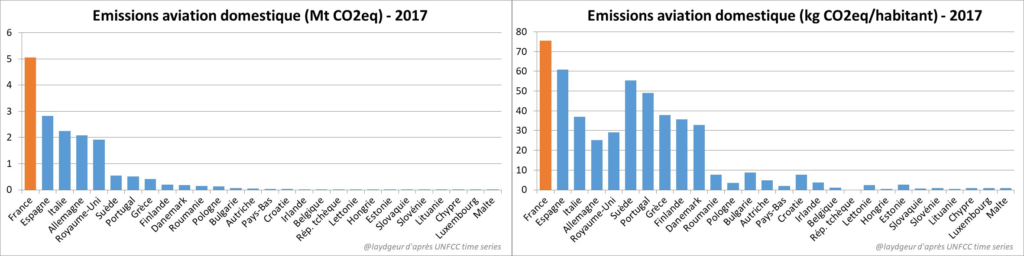

To understand this, look at the emissions from domestic aviation in EU countries. Yes, the figures are correct, and clearly, our domestic aviation emits twice as much as other major European countries! Even if you look at the emissions per capita, we still “win” hands down However, with our high-speed trains, we should travel less by plane, right?

Actually, we often forget it, but France is 1) a hexagon, 2) an island not far away (Corsica), and… 3) a good dozen territories scattered around the world. And flights between all these places are classified as domestic plane traffic…

Image source: Wikipédia

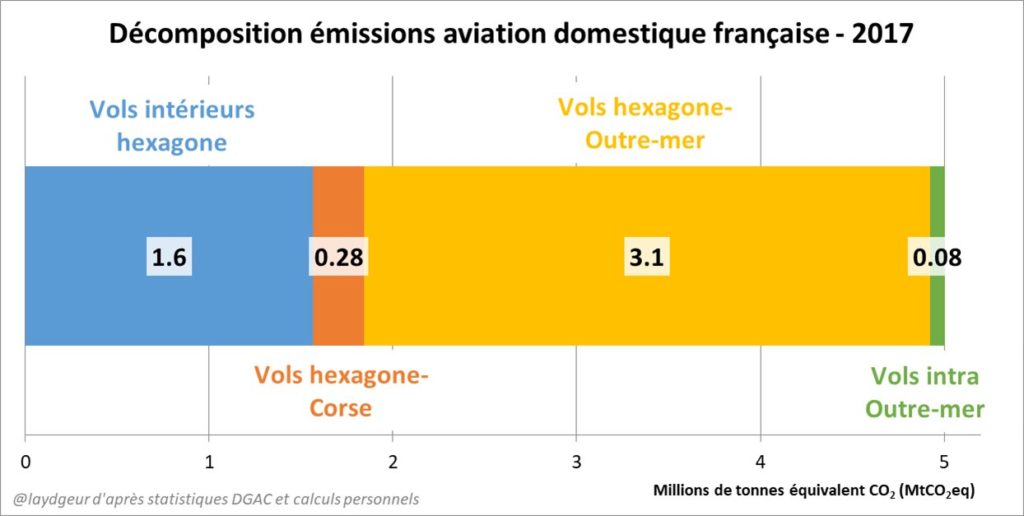

Weirdly enough, I couldn’t find emission assessments for the different categories… I then did the calculations myself, listing one by one all 200 air connections from the DGAC statistics. What is essential to keep in mind is, as usual, the order of magnitude.

Thus, here follows how French domestic aviations emissions are distributed. Yes, you read that correctly: French domestic air traffic is responsible for “only” 1,6 million tonnes of CO2 emissions!

Metropolitan/oversea flights account for only 14% of passengers but emit over 60% of total CO2. The physical laws are what they are: the further you go, the more CO2 you emit, despite the better individual performance of long-distance aircraft.

Of course, these emissions only correspond to the combustion of kerosene. If we wanted to be complete and really compare with the HSR carbon footprint, we would have to add the emissions to produce the fuel, the operation of the airports, maintenance, etc.

Let’s play the game!

Now that we have the train AND plane carbon footprints, let’s compare them!

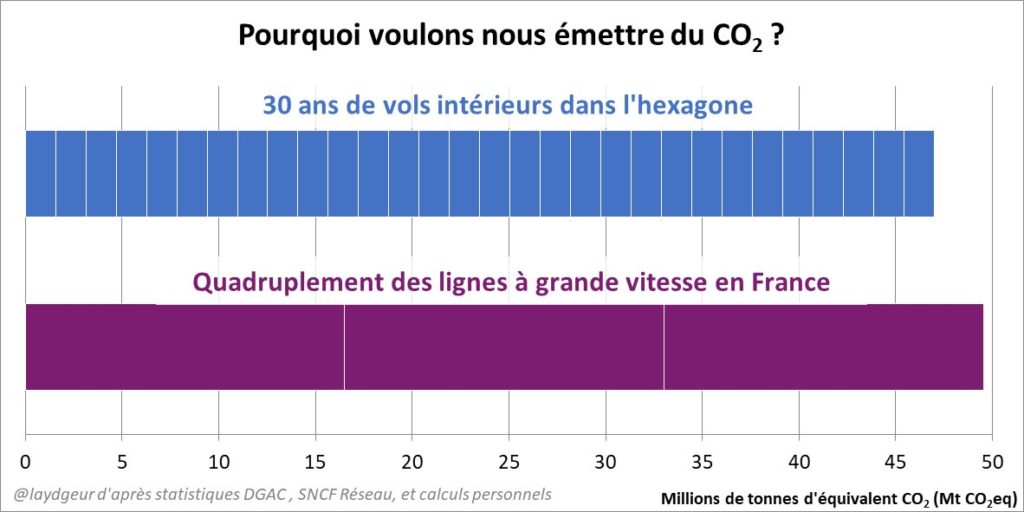

French Domestic flights emit 1.6 million tonnes of CO2 per year. For the same amount of emissions, we could build 250 km of HSR per year (remember the average ratio of 6,200 tons of CO2/km of HSR).

As a result, the emissions to rebuild the entire current high-speed network (2,600 km) represent just under 11 years of the emissions from domestic flights in France.

Let’s take a step back. France aims to reach carbon neutrality by 2050. In the 30 years between now and this goal, for the same emissions as domestic air traffic, we have the opportunity to almost QUADRUPLE our high-speed network.

Quadrupling would actually certainly be useless: it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see where the current gaps are. With this 2-minute hand-crafted route, simply by doubling the existing network, almost all domestic flights are covered by HSR…

Some people say that building new rail infrastructures emits far too much CO2 and that it would be better not to do so, as air travel would ultimately emit less. Though, the reality is different.

Take for example a scenario in which we decide today to simply double the existing high-speed network. This would make it possible to cover the French territory and ensure mass, fast and carbon-free transport between the main French cities. With such a network, domestic flights could virtually disappear (flights to Corsica and the French overseas territories would remain the same). Only certain diagonals would remain, such as the Nice-Rennes, which would only carry a few thousand passengers per year.

The CO2 emissions generated by this scenario would be in equilibrium compared to a business-as-usual scenario in just… 11 years. Only 11 years to pay off this CO2 debt, and all the years after that would be a net benefit on emissions compared to a scenario where domestic airlines were maintained.

Airline advocates will undoubtedly retort that the efficiency of aircraft is increasing. This is true! Efficiency has increased worldwide by 3% per year on average over the past decades. But these efficiency gains are increasingly difficult and costly to achieve, and above all, they do not compensate for the increase in air traffic, which means that global CO2 due to air traffic emissions have increased. by 2% per year on average since 1960 (which has increased to +5% per year since 2013).

Despite the promise of a hydrogen-powered aircraft that has created a media buzz but whose technological maturity is so low that even Safran acknowledges that “it is difficult to envisage certification and entry into service before 2040”, it is time to understand that a reduction in air traffic is essential if we wish to respect our climate commitments.

So… What are we waiting for??

The discussion lies elsewhere

We know how trains emit less CO2 than planes. We now know that even taking into account the infrastructure and its maintenance, the train still has a very clear advantage over the airplane on French territory: it is once again a KO. The figures presented in this article are moreover rather accommodating for the plane because we could have mentioned the carbon footprint of the construction of airports, their access roads, and the manufacture and maintenance of planes, …

Beyond the figures, the question is not so much whether these line constructions pay for themselves in 10, 20 or 30 years, whether the high-speed network should be doubled or tripled, or even whether the TGV is relevant everywhere.

The fundamental question to be asked is whether we prefer to emit CO2 for ephemeral air travel or to build sustainable infrastructure and provide ourselves and our descendants with low-carbon long-distance mobility. It is a societal choice that we must discuss collectively while taking into account that being CO2 neutral is only a step. Existing infrastructures or new ones can no longer be built at the expense of the great forgotten factor of this century: biodiversity. This could be the subject of a 3rd article, who knows?