Glamourous shots of private jets belonging to DJ Snake or Kylie Jenner, thirty million euros worth of brand-new cars destroyed for the shooting of a James Bond film, Tom Cruise greeted by French fighter jets at the Cannes Film Festival, a Hellfest music festival siphoning off water from a region already under hydric stress to save its festival-goers from fainting…

It’s hard to tackle our own cognitive dissonance when we sink into the spongy seats of a theatre, a cinema or when we cheer a rock star on the main stage of an enormous music festival. There is something rotten in the realm of culture.

But what this cognitive dissonance tells us is the sum total of an important series of questions: is this kind of culture sustainable? If it isn’t, do we want a world without culture? And if not, what kind of culture do we want?

A culture that’s part of the problem

Culture, a hyper-consumerist sector…

The cultural sector is considerable, notably including newspapers and publishing, film, live shows, heritage, architecture, visual arts, video games… and its fossil fuel needs are equally considerable:

- Culture and leisure come third as a reason for travel among the French population (just behind work and shopping);

- Merely travelling to the cinema produces the equivalent of nearly a million tons in CO2;

- Culture represents by far the biggest consumption of data on the internet (approximately 60% of gigabytes consumed online, including VOD and SVOD, video games, media… and more than 80% if one includes pornography which is part of film production and publishing);

- It concerns tens of thousands of buildings that are often very dependent on fossil fuels. The carbon footprint of registered auditoriums is around the equivalent of 1000 tons of CO2 per year (of which 30 to 50% come from gas heating):

- It is also an enormous driving force in official tourism marketing for an area. For example, the Avignon Festival guarantees town-centre restaurateurs and hoteliers close to 60% of their revenue. Likewise, the quasi-totality of the Louvre’s carbon footprint (3,4 million tons of CO2) comes from the arrival by plane of its foreign visitors.

…which must drastically reduce its carbon emissions

One can already hear the criticisms: the cultural sector brings us so much, why condemn it for its carbon emissions? For a start, we can cast doubt on the fact that all of culture brings so much to us and risk entering here in an endless debate on the quality of art. Even though this debate is no doubt a passionate one, our culture includes, without distinction of quality, the novels of Annie Ernaux, Marc Lévy and Sylvain Tesson, the C8, Arte and Blast TV channels, Z Event, the Raving Rabbids or the latest opus of Animal Crossing.

Worse, this argument on what culture brings to us implies there should be a “cultural exception”. Yet this exception is demanded by all sectors, and all have very good reasons to do so: cement manufacturers bring so much to us because they build houses, why ask them to reduce their carbon emissions? The National Low Carbon Strategy is clear: we must reach carbon neutrality by 2050 and reduce all national carbon emissions by 40% between 1990 and 2030 to respect the Paris Agreements.

It’s also a case of looking at the problem backwards: we are not condemning culture for its carbon emissions, it’s the carbon emissions which are condemning culture! The more significant these are, the more culture depends on fossil fuels which are warming the climate and are expected to become scarce.

An economic model that needs revising from top to bottom

A mad dash for growth…

Most renowned artists and the trades and professions around them (producers, broadcasters, booking agents, distributors, internet platforms…) are today dependent on hyper-intensive energy-consuming models.

Music or showbusiness artists, for example, depend more and more on touring and festivals. Namely because with a remuneration of 0,0034 dollars per listened music track, only 1% of music artists receive a minimum wage through streaming and because, in the meantime, sales in the physical media market (CD, vinyl) have collapsed, and streaming has not made up for loss of value.

Unsurprisingly, the artists who are most successful at making a living receive the quasi-totality of their revenue from the tours they do via concerts or festivals. And those have a tendency to increase at an unchecked rate.

To attract that many crowds, these artists demand more and more top billings with equally increasing fees and technical requirements. Thus, Coldplay travels with no less than 2 kits of 32 articulated lorries on the road (for their “ecological” tour), Rammstein accounts for almost 100 articulated lorries and 7 cargo planes for their tours and burns no less than 1000 litres of heating oil for their pyrotechnical effects at each concert (something the group proudly displays on social media).

This logic has nevertheless already seen its limitations: a few years ago, DJ Snake had to cancel his trip to the Francofolies at La Rochelle because his technical needs “didn’t fit” the assigned stage, according to an ex-employee of the festival who wishes to remain anonymous.

…that artists are complicit in

Unfortunately, celebrities don’t often set an example in the matter. The arrivals of Tom Cruise or Omar Sy via private jet at the Cannes Film Festival were more remarked on for their effect on the audience present, than for their effect on the climate. Yet the consequences are more far-reaching than the size reduction of the red carpet and its recyclability, hailed by public authorities.

But in truth, the impact of celebrities doesn’t stop there: they also attract considerable audiences. These headliners exist to attract more and more people who come from further and further away. And to ensure that that is the case, large venues such as big festivals implement a “territorial/regional exclusivity clause”. In this way, when Céline Dion is scheduled to perform at the Vieilles Charrues Festival, she is not permitted to go on tour in France for a timespan ranging from several weeks to several months, before and after the festival.

A director of the Scène de Musiques Actuelles who wishes to remain anonymous told us recently that he hosted electronic music artists who do up to three or four concerts in different countries on the same night, one after the other (often in Amsterdam, Berlin, Paris and London)! The economic attraction is significant, with fees that sometimes oscillate between 10 000 and 15 000 euros per live set.

Fewer dates, more people?

Artists therefore play fewer dates per region with more and more people. The tours of the Zénith concert arenas or the big summer festivals depend on this hyper-concentrated economic model. For largely financial reasons, the intensity of bookings is increasing (the number of artists scheduled to perform per year, per season, etc.) and the bookings themselves are growing more and more extensive (the kilometres/miles travelled by artists continue to rise with fewer and fewer performance dates in each region).

Certain artists might counter with the argument that it is better for them to travel than for audiences to travel. Except that the current performance rate is not sustainable because the increase in artistic fees and technical requirements (for which artists and their managers are directly responsible) force organisers to poach/attract even more audiences that come, inevitably, from further and further away. All of this resembles, according to a tour booking agent wishing to remain anonymous, an enormous “arms race”.

Unfortunately, as we will see, a handful of audience members arriving by plane is enough to significantly reinforce the carbon footprint of a cultural event.

A bit of flying… and emissions take off

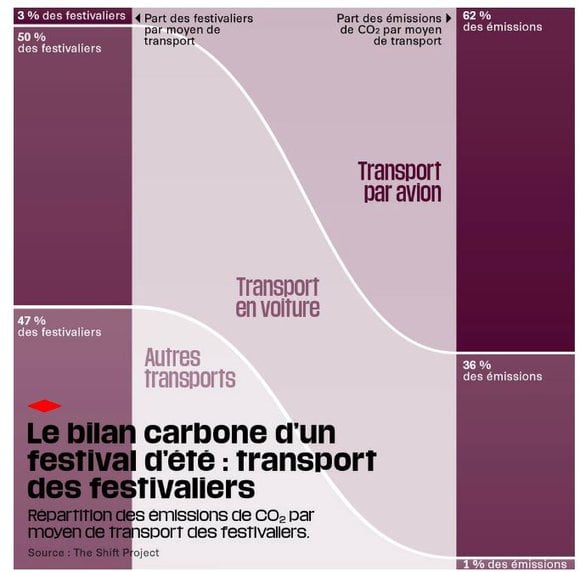

The Shift Project has estimated that if only 3% of festival-goers attending the Vieilles Charrues Festival come by plane, they account for more than 60% of carbon emissions linked to public transport! This statistic is not overestimated when one remembers that, on average, 4% of festival-goers in France come from foreign countries.

And we haven’t yet mentioned festivals that are otherwise more dependent on flight bookings for the arrival of their audiences. At Tomorrowland, close to 25 000 festival-goers fly in via “party flights”. As for Burning Man, it is estimated that almost 20% of festival-goers are not from the North American continent and it is unknown how many American festival-goers fly in…

The same goes for film or contemporary art fairs: the majority of carbon emissions of large events come largely from the travel of their audiences, particularly those who fly in by plane. Whatever the case, transport always ends up ahead in the carbon footprint of cultural events.

Who is responsible for the carbon emissions?

A systemic problem…

The problem is systemic and involves a large variety of players. A festival or venue involves organisers, public bodies, service providers, artists, performers, managers, spectators… but are they all equally responsible?

Let us ask the question differently: can we consider that the consumers of culture are the ones who decide the artists’ travel means or the size of the venues? Putting the blame on the audience or visitors very quickly appears to be a replication of the hypocritical waste-sorting strategy by food-processing giants.

…of which the decision-makers are well-known

Who decides the increase in capacity if not the senior management of cultural organisations and the public bodies that support them, who use these enormous events to spread their local influence? Who decides on the size of the venues or the installations if not the artists and their managers who validate their decisions? Who signs off on constructing an 85 million square-metre water tank in Mexico for the filming of Titanic, if not James Cameron and his partners? Or to blow up a real Boeing 747 for the making of Tenet, if not Christopher Nolan?

What is clearly apparent here is that the responsibility indeed lies with the producers (in the economic sense of the word “producer”, in contrast with the consumers who are the audience members/visitors).

And where the artists take part in a fantasy of overconsumption

The place where artists play a distinctive role, exactly like high-level sports athletes, is in the propagation of a certain fantasy.

How many young people who follow them on social media begin dreaming to be like them? How to stop them believing that success means wearing luxury designer clothes, spending your holidays in all four corners of the world and travelling by jet all year? And don’t try asking DJ Snake, his reply won’t necessarily be pleasant…

In contrast, one can regret the fact that artists who make frugality desirable are not given a larger showcase: actors like Jacques Gamblin or Clovis Cornillac, who have recently favoured using a bicycle or public transport to get to film sets.

If nothing changes, everything will change… and it will be unpleasant

A non-essential culture?

Make no mistake, wherever culture hasn’t made its transition… it will be the first to be sacrificed. This is what happened during the COVID-19 crisis, where all shared cultural activities like moviegoing or live entertainment were deemed “non-essential”.

During the London lockdown, artists – who unlike their French counterparts, were not protected by unemployment insurance – were even gently encouraged to take other jobs. “Rethink. Reskill. Reboot”, proclaimed Boris Johnson’s ad campaign.

It’s also what’s happening this year in the concert halls that aren’t able to face the soaring energy costs, and as a consequence decide to make employees redundant or close the venue for several days a week. This is the case, for example, for the Scène Nationale de la Filature de Mulhouse where the energy costs risk increasing the budget by about 600 000 euros a year, or the Halle Garnier where electricity will cost a further 200 000 euros in the annual budget.

There are only a few decisions possible to offset this increase and none of them are pleasant: increase the ticket price, lower the number of artists scheduled to perform, reduce the venue’s payroll.

Multiple risks

One could mention other risks:

- The hydric risks: which affected the Hellfest festival this past summer, where it was necessary to spray the participants with a firehose in an area where farmers had no more access to water and where firefighters weren’t sure whether the groundwater would last for the duration of the festival. The result: almost a thousand fainting spells in the first weekend;

- The insurance risks: the more significant the flow of goods and people are for a cultural event, the more significant their exposure to pandemic, energy or hydric-related risks will be. Consequently, insurers may not wish to cover them anymore;

- Maladaptation: it is now certain that the music hall currently named la Sirène at La Rochelle will be very aptly named by 2050… in the sense that it will be underwater.

Three possible transitions

There are, in summary, only three ways to achieve the ecological transition of a cinema, concert hall, music fair or festival:

- Undertake technical improvements (thermal renovation, changing the heating systems, car-pooling electric vehicles where pertinent): to reach, at maximum, a 20 to 30% reduction in carbon emissions according to the estimations of The Shift Project;

- Take significant reorganisation measures, otherwise known as sobriety: share spaces and programming, slow rates of productions, defend eco-conception, reduce capacity when it is not adapted to reach a local audience… measures that take the Paris Agreements seriously;

- Allow energy costs to skyrocket and watch the venue in question die. Poverty is without any doubt a very effective way of emitting less CO2, but it’s unlikely to be the most desirable one.

What is the culture of the future?

1/More local performances…

The first lever to achieve this is insourcing. In the first instance, insourcing artistic performances. One can already hear the teeth-grinding by imagining the culture sector closing in on itself, but that does not mean closing its borders.

One of the pioneers on this subject is without a doubt Jérôme Bel, an internationally-renowned choreographer who definitively gave up flying in 2019. Since then, his company has broadcast more of his shows internationally than ever before, and his carbon footprint is said to have passed from the equivalent of almost 60 tons to approximately one ton of CO2 per year, according to the executive director of the company.

How is this possible? When Jérôme Bel puts on a show in Europe, he tours only by train and by ferry. To recreate his show on another continent, there are two options: either Jérôme Bel rehearses by video call with a foreign performer who in turn will take the show on tour by train, or Jérôme Bel creates “a reassembling protocol” of his show, which two local assistants follow on another continent to recreate and then take the show on tour themselves… by train!

One could believe that this practice is exclusively reserved to minimalist aesthetics similar to those of this particular performer. Yet they are already in operation in plays, with considerably less ecological specifications at Stage Entertainment, who recreated The Lion King or Mamma Mia in several countries at the same time. Proof that this logic can be replicated.

This poses a question on tomorrow’s international exchanges: if we are so attached to cultural diversity, why do the African, American or Asian artists who visit our country stay for so short a time? Must the experience of the host country’s inhabitants stop at a single showing or exhibition?

2/ More local purchases

Purchases are a sizeable part of carbon emissions caused by the production of works of art but also the carbon footprint of cultural organisations. To insource them, resource networks and shared technical pools are developing all over the country. The goal: to give cultural venues the means of creating with what they find locally.

This is the case, for example, with the Théâtre de l’Aquarium, where the La Vie Brève theatre company has just installed – with the help of the Ile de France Region – a resource workshop with an appointed employee to manage the stock and train any artistic teams hosted by the venue. The idea: that all hosted companies and orchestras can use the props and materials in storage and be assisted in the eco-conception of their scenery.

The same goes for the film world, with the development of a workshop in the Montreuil cinema which Brut has just made a video about.

This logic of a circular economy is now structured around dedicated networks, like the REFER in Ile-de-France (which the Réserve des Arts à Pantin or the Ressourcerie du Spectacle at Vitry-Sur-Seine are part of, for example) or the RESSAC on a nationwide scale.

This logic also allows one to opt for more local transport and delivery services, sometimes via cyclo-logistics: an approach advocated by organisations such as Slowfest. Larger endeavours like the I’m From Rennes festival ou Les Francofolies already call on a similar service provider for transporting their technical requirements on site via cyclists!

3/ A lever for regional transition

In developing this logic of a circular economy, resource centres and material libraries ensure non-outsourceable jobs in the cultural sector. But by functioning locally, these cultural actors can bring an eco-transition to the area in which they find themselves.

Let us imagine for a moment the shock of demand for Brittany farmers if even the mere million of annual festival-goers in the region consumed a local, organic and vegetarian diet (a challenge for the land of the sausage galette). But it is not impossible: even the Vieilles Charrues festival, which serves tens of thousands of litres of beer every day via underground pipelines, supplies beers from Alsace and Brittany. Why not take advantage of the opportunity to also ask for an organic supply with such a guaranteed demand?

Likewise, we know that the restaurateurs and hoteliers in the centre of Avignon achieve 60% of their annual revenue during the festival period. If their service providers were selected on a criteria according to distance or farming practices, the festival could have a strong knock-on effect on the region.

4/ Reduce capacity, a necessity

However, large cultural events will not be able to massively insource their needs without reducing their capacity. Will we really be able to forgo a massive consumption of fossil fuels to gather 400 000 people at Clisson or Carhaix? Will it be possible to feed the festival-goers of Avignon with a local diet in 2030? Will we be able to maintain our Zénith concert arenas in good condition without oil?

In the Decarbonise Culture report of The Shift Project, it is estimated that an event which passed from 300 000 to 30 000 people in a rural region could divide its carbon footprint by 30 to 50. It is unlikely that this will be to the liking of the performers, for whom it is more advantageous to do fewer dates in areas where capacity allows for the payment of more important fees. Unfortunately, this practice is not sustainable. It’s in this sense that the Panoramas Festival has recently decided to reduce its capacity, for both economic and ecological reasons. Eddy Pierres, the director, evoked the necessity of “a return to sobriety”.

Where adapting to the region has a doubly beneficial effect is that, as well as depending more on local input, events with a reduced capacity can more easily share bookings with other areas in the region. If you gather 300 000 people in the middle of a rural zone, the fact that a commune located 30 kilometres away is booking the same performer the following week is an enormous source of tension. This is not the case if you can count on your population base to fill capacity.

5/ Slowdown or perish

A slowdown involves more performance time in each region and fewer kilometres between each performance to reduce the use of carbon-heavy transport. Such a decision allows artists to meet more local audiences and even imagine other forms of exchange.

In an opinion piece written at the start of lockdown, the DJ Simo Cell demanded artists fly less and suggested spending more time performing in each country to do collaborations with other artists, give masterclasses in electronic music schools, work on a new album… There is no shortage of possibilities.

This is already what certain companies are doing. For example the Organic Orchestra music company, which, upon arriving in a region, only tours there by bike and gives many artistic education workshops (which raise children’s awareness to the importance of energy).

This slowdown has also been promoted by certain film productions. Thus, Camille Etienne’s documentary Pourquoi on se bat was indeed partly filmed in Iceland…which the production team reached by sailboat. For his part, Cyril Dion is said to have preferred to resort to videoconferencing or filmmakers on other continents for the making of his Un Monde Nouveau series, recently broadcast on Arte.

In another genre, an appeal has recently been made that the transport of scenery for the 1 500 productions of the Festival Off in Avignon be done by freight train and no longer by road.

6/ Eco-conceive the arts, so that the arts may endure

Eco-conception is necessary to limit the logistical needs of artistic productions. This means working on purchases (raw materials, end products, etc.), the transformation process (the functioning of workshops), the energy needed for showings (far more significant for Coldplay’s massive screens than the candle-lit concerts held at the Sunset Sunside), the energy consumed on tour (determined by the number of vehicles on the road, transport of the sets and the type of vehicle) and the scenery’s end-of-service life.

Even with an art form as energy-consumptive as opera, interesting projects are underway, notably in the standardisation of the structures of scenery as proposed by l’Opéra de la Monnaie in Brussels. This type of measure limits the impact on purchasing, transport and the productions’ end-of-service life.

7/ Educate and change public policies

It is therefore clear: if the gigantic scenography, capacity-increasing race for performance fees or intensive tours generate so many carbon emissions, it is hard to separate artists from their carbon footprint.

Hence an urgent need to educate them and the cultural professionals around them. The higher cultural learning establishments educate almost 40 000 students every year (with close to 10 000 graduates per annum). An initial and continual education policy therefore appears to be absolutely necessary for the cultural sector to embark rapidly on a path of resilience.

In addition, certain regions have already put in place ecological bonuses for productions. This is notably the case of the Ile-de-France region for film sets. But to ensure a follow-up, the cases are overseen by the ADEME. Short of wanting to put an ADEME employee behind every cultural project (which would be a highly job-creating transition), it seems urgent to educate both cultural subsidisers and actors.

An ambitious public policy combining education, impact measures, calls for projects and eco-conditional aid should emerge and become a reality. This is the promise, for example, of the Plan d’Action touted by the CNC. The fact remains that this action plan does not appear to be the priority of the government, which gives almost 430 million euros for the cultural sector to “digitize”, deploy the use of 5G and accelerate research on 6G… and less than 30 million euros for sustainability in its stimulus package…

Will we let culture die or will we change it so it can be sustainable?

It is because we wish to preserve a world where culture continues to move us emotionally that we want it to break its dependence on fossil fuels.

The consequences of this dependence are severe: climate change for one, but also – as we have previously seen for venues closing because of the energy costs – the endangerment of all who work there. To reiterate Adam Philips’ expression, “if the art legitimates cruelty, I think the art is not worth having.”

Without this necessary transformation, we collectively accept that we are heading towards a society consisting only of work, consumption and sleep (any resemblance to an episode of Black Mirror, the movie Soylent Green or a global pandemic would not be entirely accidental).

Translated by Daniel Rawnsley