Name and Shame is nothing new. From Mandela’s denunciation of apartheid to Greenpeace’s preferred strategy, Name and Shame has been used for decades. This was a promise made by President E. Macron, who wanted to use the Name and Shame to encourage companies to improve their practices in the area of professional equality.

The implementation of the Paris Agreement’s ambitious targets will depend on the contributions of states and non-state actors, in particular large multinationals. These companies have specific environmental protection obligations, but there is no consensus on the nature and extent of these obligations. In the absence of relevant (and demanding) regulations, is Environmental Name and Shame an effective weapon to achieve the desired results?

Although the principle of Name and Shame is very easy to understand, measuring its effectiveness (and legitimacy) is another matter entirely. Once again, let’s get out of silo thinking and analyse its multi-factorial impact.

What is Name and Shame?

Literally, “name and shame” means… “to name and shame”. The practice of publishing the names of individuals or companies involved in activities deemed to be reprehensible. This is theof the key measures of Law 2018-898 of 23 October 2018 on the fight against fraud, with the introduction of a French-style “name and shame”. Last year, Law 2019-486 of 22 May 2019, known as the PACTE Lawon the growth and transformation of companies adds that: ‘the decision issued (i.e. the administrative fine) by the administrative authority may be published on the website, and at the expense of the person sanctioned on other media‘.

In other words, in addition to being a bad student, you could have your name on the board. This is a new situation for companies: damage to reputation is now a risk to be taken into account, at the same level (if not higher) as financial sanctions. The prospect of bad buzz or a tarnished reputation can potentially cost a company far more than a few thousand euros.

Brune Poirson, Name & Shame lover

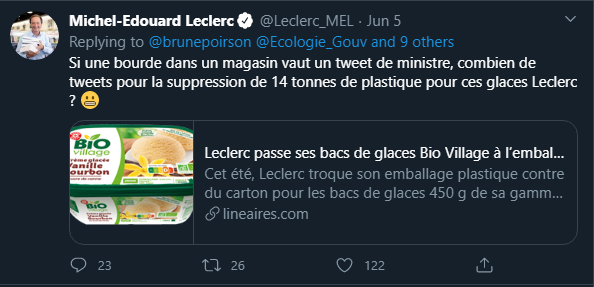

Before going into an in-depth analysis of its effectiveness, it is interesting to see how Name and Shame has been used in the last two years. Take for example Brune Poirson, Secretary of State to the Minister for Ecological Transition and Solidarity before the reshuffle. Wishing to promote the #LoiantiGaspillage, she used Name and Shame by slamming E.Leclerc directly on Twitter. BEWARE ! The following may offend the sensibilities of younger people. Below is a rare image that sums up Brune Poirson’s action in the Macron government in 3 years:

I told you it was shocking. Moreover, the president of Leclerc, cornered, felt obliged to respond. I will let you judge the quality of his response below. We can immediately see that these leaders have taken the measure of the stakes and are not at all out of touch:

Of course, everyone had their own interpretation. Why the shaming? Did Brune Poirson jump at the opportunity to promote the Anti-Waste law, thus reminding us of its great usefulness in public action for the ecological cause? I imagine that E.Macron was convinced and reappointed her to the Castex government…

Let us return to the original question. Was this shaming effective? The answer is yes. The shop has been called to order and should certainly not do it again. It is also a potential warning to all others in the same situation. This Name and Shame was also relevant for several reasons: A tweet is 15 seconds of effort. Secondly, it is not really expensive (come on, in proportion to B. Poirson’s salary). Finally, it is above all terribly fast and efficient: rather than going to court, politics has used the court of public opinion, which, as we know, can carry a lot of weight in the age of social media.

So we have an initial response. Yes, Name and Shame can be effective. But is its use restricted to the political sphere?

Name and Shame as a citizen counter-power

Of course, Name and Shame will seem completely unnecessary to people who are happy with the system and believe that government and business are doing their best to combat climate change and the slaughter of biodiversity. Yes, there is such a thing, if you live in a cave, or simply don’t care about others and the future of a part of the human race.

For the others, it differs slightly. We often think that we cannot do anything against the ‘multinationals’, against the ‘system’. It is certain that achieving systemic change will not be achieved by your goodwill alone. This is where the group effect comes in. Class actions have not been very successful in France, but there is another way to group together easily and quickly: social media. Through two examples, I prove to you that it is possible to move the lines. Firstly, by calling on Air France last July. In addition to lying about its communication, the company lied about the calculations of the impact of the flight:

Result: a snowball effect, Valérie Masson-Delmotte was tagged several times and the next day tweeted about Air France’s misleading communication. They have since corrected this ‘CO2 neutral flight’ lie.

A second example is Laydgeur, which called Dassault to order because, in addition to its sickening communication on the flight’s climate impact, it had not published its carbon footprint, which is an obligation. Miracle ! A few days later :

Again, was Name and Shame effective? The answer is yes.

Let’s make one thing clear: it is in no way the role of citizens to ensure that groups that make billions in turnover respect the rules. No one will make me believe that Air France did not knowingly write “CO2 neutral flight” on its website to ease the user’s conscience, so that he can believe that flying does not really have an impact. It is not up to professionals in the field of carbon neutrality, such as Renaud Bettin, to call Velux to order on its misleading communication. We all have better things to do.

It should also be noted that this Name and Shame concerns a very restricted perimeter of action, and that one must have the means to do so. I don’t need to remind you what happens to whistleblowers when they expose real scandals. There is a first limit to Name and Shame, which we will explain in more detail below: you can disturb some companies, but not too much either. Correcting a line on the Air France website is not the same as saying that Total bought oil from the Islamic State. The consequences can be quite different.

NEWSLETTER

Chaque vendredi, recevez un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

+30 000 SONT DÉJÀ INSCRITS

Une alerte pour chaque article mis en ligne, et une lettre hebdo chaque vendredi, avec un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

No universal rule for the effectiveness of Name & Shame

The effectiveness of Name & Shame shares a common characteristic with the social tipping point: it is heterogeneous in time and space.

The scientific literature suggests that Name and Shame can contribute to behavioural change among companies, but ‘the degree to which shaming works to change behaviour varies widely across companies and sectors‘ (Haufler 2015, 199). An additional difficulty is that it also depends on the political regime.

The incentives to change behaviour in the face of international condemnation vary between regime types. In democracies and hybrid regimes – which combine democratic and authoritarian elements – opposition parties and a relatively free press paradoxically make leaders less likely to change their behaviour when faced with international criticism. In contrast, autocracies, which do not have these domestic sources of information on abuses, are more susceptible to international ‘shame’.

By using Name and Shame data from Western press reports and Amnesty International, Virginia Haufler demonstrates that Name and Shame is associated with improved human rights outcomes in autocracies, but no effect or deteriorating outcomes in democracies and hybrid regimes. This observation immediately made me think of E. Macron’s appointment of Gérald Darmanin: in our beautiful democracy, you can be accused of rape and be Minister of the Interior. No shame then.

Is the effectiveness of Name and Shame the same for all companies?

There is no single solution for all companies. There are three types of business-to-business relationships: business-to-consumer (B2C), business-to-government (B2G) and business-to-business (B2B). Of course, a company can have two or even three types of relationships. What does the scientific literature tell us about these relationships?

The most prominent examples where ‘shame’ has influenced corporate behaviour are in the areas of CSR and environmental management. In these examples, humiliation is effective because these companies are in direct contact with their consumers (B2C). Remember, for example, the Slip Français scandal, or Findus and horse meat: these two events cost these companies dearly. The damage to their image directly affects their business, especially if consumers decide to boycott the brand.

B2B and B2G relations

Many large companies are engaged in business-to-business (B2B) or business-to-government (B2G) relationships, where there is little or no pressure from individual consumers. Name and shame then works differently. States are in principle able to use this procedure on a company for non-compliance with the law, but there are at least 3 limits to this. Firstly, states may be inclined to blame companies falsely, for example to cover up their own incompetence or non-compliance with international agreements (ohhhh ”Redirect responsibility”, sound familiar?).

Secondly, in economically less powerful states, there may be a serious reluctance to use name and shame on companies, depending on their economic weight. Can you imagine the Finnish government being able to name and shame Nokia, which represented 70% of the market capitalisation of the Helsinki stock exchange in the early 2000s?

The third and final case is business-to-business relationships where neither reputational damage nor a direct relationship with the state would be a deterrent. A simple example that will speak to everyone: Bruno Le Maire who wanted to tax Amazon (rightly so, which has been practising shameful tax avoidance for years). Unfortunately, his courage did not last long. When Jeff Bezos blows, Bruno le Maire gets a tornado. Now imagine Barbara Pompili calling out Amazon for its carbon neutrality…

Money or climate, you have to choose

I can’t count the number of politicians I’ve heard say ‘I expect companies to take the measure of climate change and act accordingly’. Quite simply, NO publicly traded company has ever taken on the challenge of reducing its climate benefit without being forced to do so. You know the reasons: shareholder pressure, maximising asset value.

In the same logic, companies will continue to make a trade-off between gains and losses with ecology. As long as the losses are insignificant, there is no reason to change the model. If they do, it is because there is a short-term interest in doing so. Not in the long term. Short term. It is exactly the same logic with the ecological Name and Shame. Companies will continue to play with the limits of legality, while playing with the physical limits of our planet. Relying on the voluntariness (excuse n°9) of companies is a folly, which only irresponsible people can hope for.

The last word

Name and shame can be an effective strategy for getting companies to reduce their GHG emissions, but only under certain conditions. First of all, the commitments (in this case CSR) must have significant benefits, such as public recognition of a successful CSR policy. Secondly, there needs to be a mechanism for fines or ‘shame’ which costs the company a lot of money if it does not respect the rules. We have seen here that this can potentially cost companies more with a B2C relationship.

Indeed, in B2G relations, shaming may become less effective, depending on the will and capacity of states. In B2B relationships, Name and Shame is not really the best strategy: there is little public information about these interactions and, more importantly, reputational damage is no longer a potential deterrent.

So the right question to ask is not ‘is Green Name and Shame effective, but rather, how effective? It is good that Air France has removed ‘CO2 neutral’ from its website, but will it make the necessary efforts to become carbon neutral? Given the repeated lies of their leaders, well helped by Jean-Baptiste Djebbari, I highly doubt it. This political issue of climate governance is also spelled out in Dahan and Aykut’s book Governing the Climate, which I recommend again.

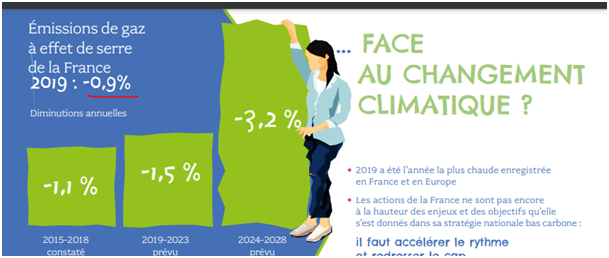

Finally, two last points. Name and shame is about the legal framework and non-compliance. That’s fine. But what if the rules are insufficient? Take, for example, France’s efforts to decarbonise its economy, which are totally inadequate compared to our commitments under the Paris Agreement. We need to reduce our emissions by 7.6%/year. Look at what the SNBC announces, taken from the latest report of the High Council for the Climate:

Given the consequences of climate change, we can simply say that our targets (and results), by being grossly inadequate, will be responsible for thousands of deaths. So understand that Name and Shame will have its limits and that the only response to the violence of climate inaction will be civil disobedience. It is inevitable.

I therefore anticipate a very clear increase in the ecological name and shame process in France in the months and years to come. As the French realise the climate emergency, they will go through stages of denial and anger, where they will seek to blame others and find culprits. Our procrastination is costing and will cost more and more: it is time to act.