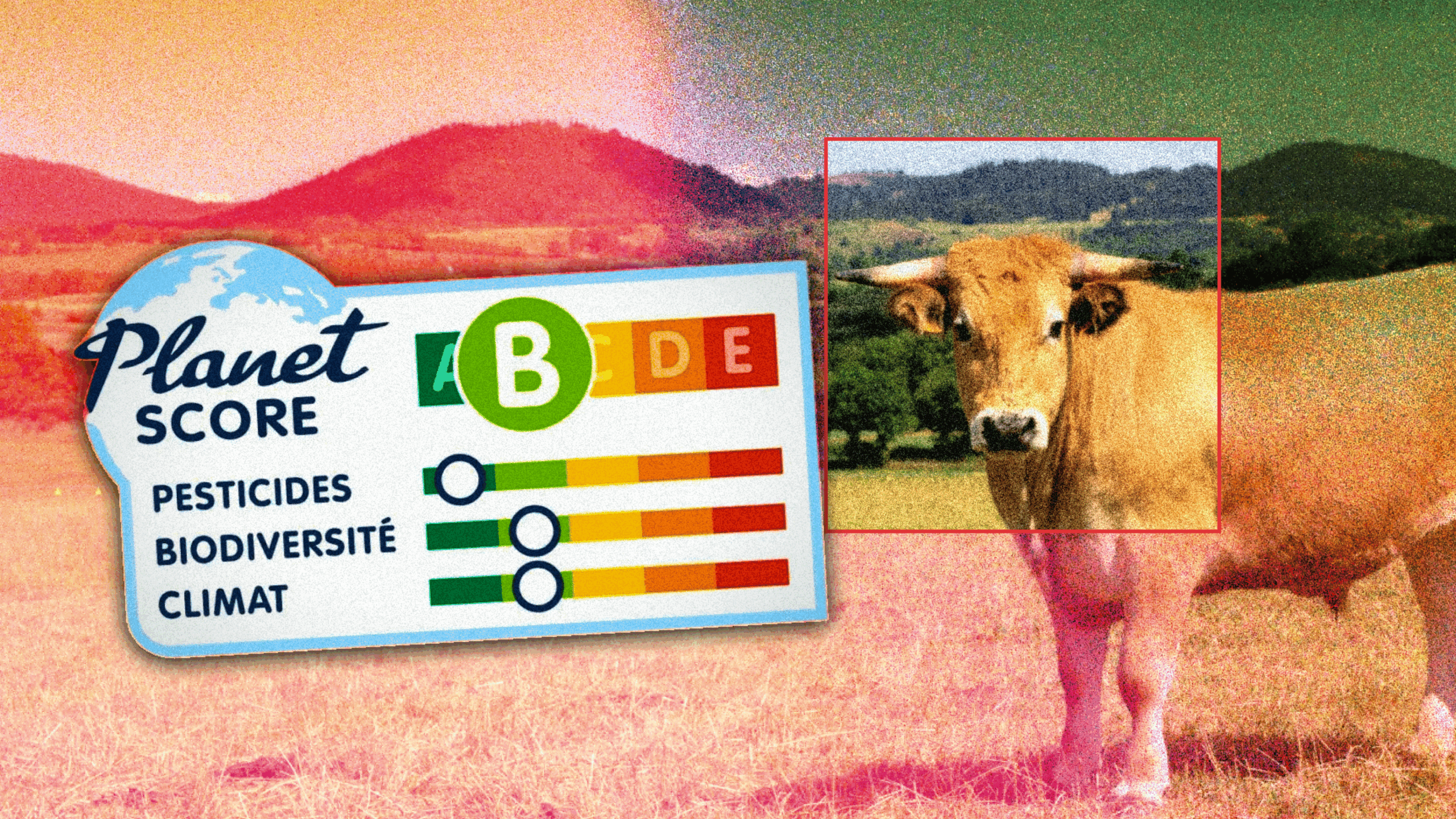

The Planet-score aims to be to the environment what the Nutri-score is to health: a label encouraging responsible purchasing while encouraging producers to make their products more virtuous. A laudable ambition, given the urgency of the agricultural and food transition.

But in practice, and unlike the Nutri-score, this environmental labelling is based on a non-transparent methodology that is biased in such a way as to underestimate the impact of extensive livestock farming, and is out of step with the scientific consensus on the environmental cost of red meat. These are practices condemned by the scientists we interviewed, including Valérie Masson-Delmotte, co-chair of IPCC Group I from 2015 to 2023. On reading Planet Score’s methodology, she denounced“a biased presentation of the state of knowledge on methane emissions, in a supposedly scientific form“.

With Planet-score, beef can be rated “B” or even “A” – a nonsense in view of itsreal environmental cost and the signal it sends to consumers. Here’s how it works.

Environmental labelling: a major transparency issue for consumers

Envisioned by the 2021 Climate and Resilience Act, the idea of a mandatory environmental score displayed on food products is a promising one. ADEME and the French Ministry of Ecological Transition are currently working in this direction by developing Ecobalyse, a calculator of the environmental cost of products. At the same time, a private initiative for environmental labelling is gaining momentum: Planet-score.

Planet-score, soon a must?

Designed in particular by the Institut de l’agriculture et de l’alimentation biologique (ITAB), the Planet-score tool saw the light of day in 2020-2021 thanks to an experiment in environmental labelling piloted by the government and ADEME. The Planet-score® trademark is now marketed by the company of the same name, and owned by an endowment fund called Solid Grounds Institute.

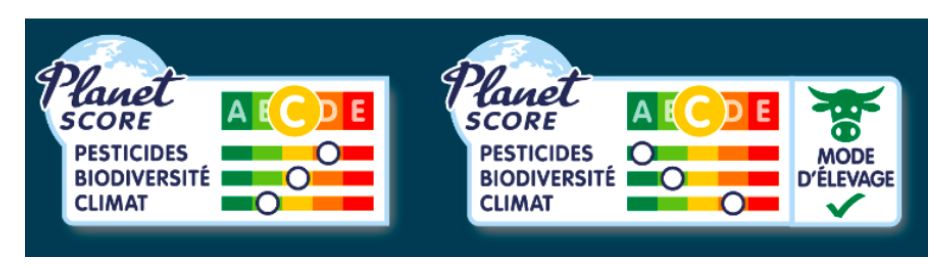

Its methodology is based on the standard Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) method, but aims to go beyond its limits (e.g. taking biodiversity into account) by supplementing it with new indicators. On this basis, Planet-score assigns each product an overall rating from A to E, three sub-scores (pesticides, biodiversity, climate) and a pictogram indicating the farming method used.

Planet-score is leading the way in the new environmental labeling battle. In addition to very favorable media coverage, the tool enjoys the active support of UFC-Que-Choisir, which has integrated Planet-score into its mobile application as early as 2023, has called for Planet-score to be rolled out across Europe in 2024 in a manifesto, and is publicly campaigning for its deployment. On its website, Planet-score also calls on recognized environmental associations such as Générations Futures, WWF and France Nature Environnement, who have lent their support in an open letter.

With 230 companies evaluated in a dozen countries, its labels are rapidly multiplying on supermarket shelves. More than 200 million packages now display the Planet-score label in Monoprix, Biocoop, La Vie Claire, Franprix and Picard stores, five major chains that have pledged to display the label on all their products.

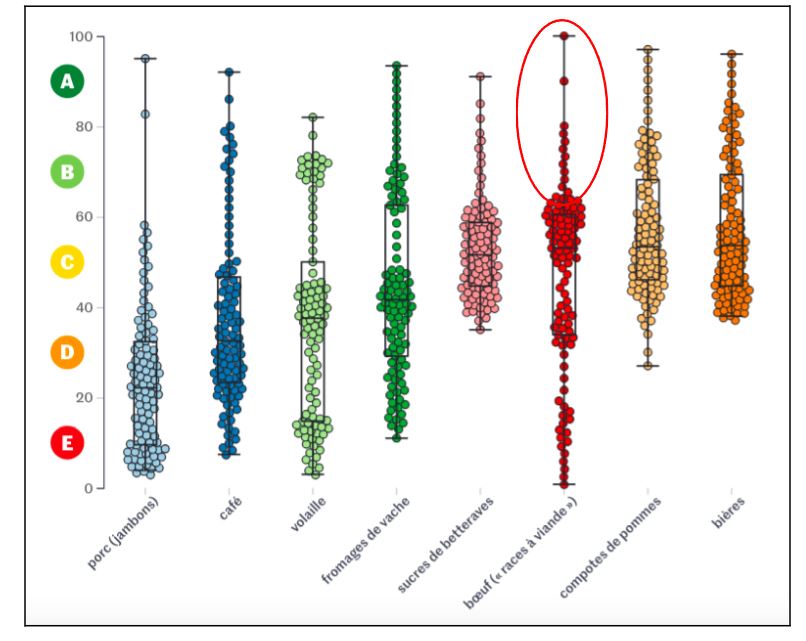

[Editor’s note: we circle]

An easy-to-read tool that aims to be transparent, scientifically rigorous and exhaustive (25 criteria in all), while overcoming the shortcomings of traditional environmental labelling: on paper, Planet-score is the perfect label.

Questionable and scientifically unjustified methodological choices for Planet-Score?

However, a reading of Planet-score’s most recent methodological note (May 2025) raises questions. Illustrating a lack of rigor, some of the figures put forward to justify methodological choices are not sourced, and few scientific studies are cited.

The methodology has not been the subject of any scientific publication (unlike the Nutri-score, Agribalyse or LCA methods). Questioned about this absence, the Planet-score team defends that“in a scientific field […] subject to very lively controversy, where the dominant system has failed to produce metrics relevant to the agricultural and food sector […], the notion of peer review raises questions“. He added: “Which ‘peers’ can claim to be in a position to judge objectively the relevance of each other’s work?“.

The calculation of the environmental score also lacks transparency. In the absence of details on the algorithm used to score products, it is impossible to reproduce the calculations solely on the basis of the methodology available. Even though the tool was initially designed by the ITAB, its director Emeric Pillet confided to us that “at present, the Institute is not in a position to reproduce a score with the formula indicated in Planet-score’s latest methodological note“.

In addition, we observe significant methodological biases that systematically converge towards the same result: greatly overestimate the benefits associated with agroecological production systems (organic, extensive livestock farming) and downplay other relevant environmental criteria, such as greenhouse gas emissions, water consumption and land use.

To achieve this result, Planet-score’s methodology can be summarized in a succession of 3 key steps. Its calculations first make several modifications to the score derived from the Agribalyse database, which compiles 12 classic environmental indicators using the LCA method (Step no. 1). The values thus obtained are then compressed (Step 2), then subjected to 13 evaluation parameters designed to capture systemic issues not covered by traditional LCA, and taking the form of bonus-malus (e.g. pesticides, deforestation, antibiotics, etc.) (Step 3). At the end of these 3 stages, the values are finally converted into an overall score.

Step 1: modify the LCA method to minimize the impact of livestock farming

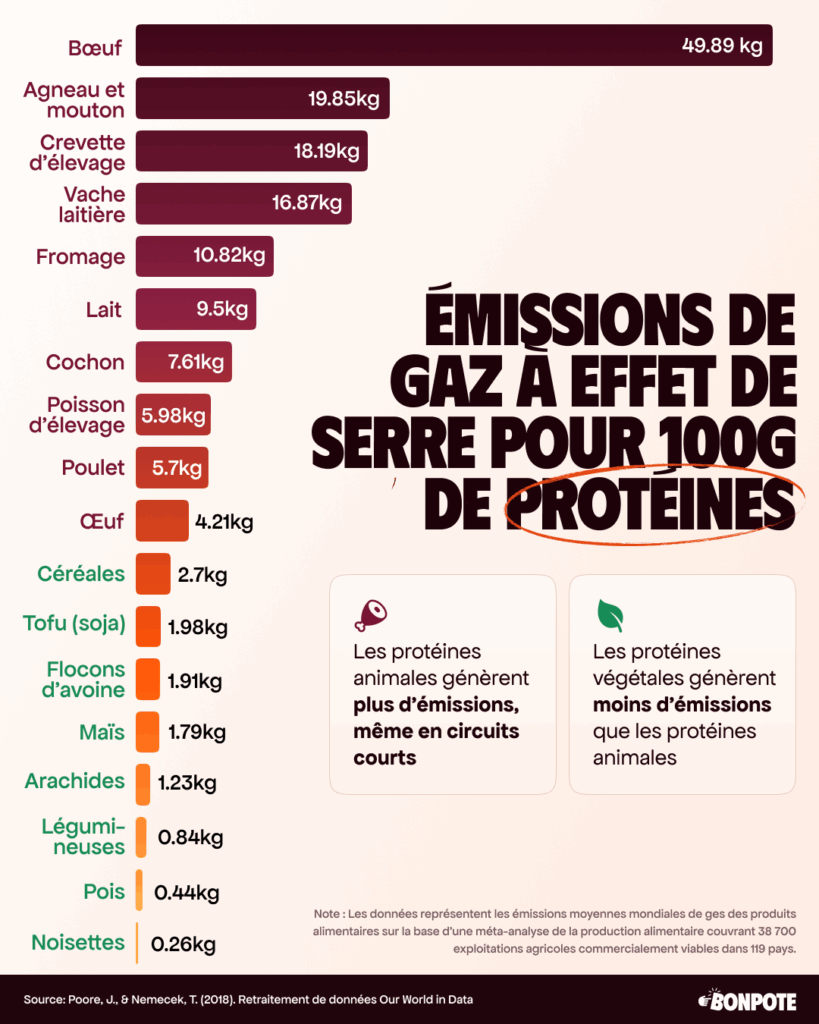

LCA is the benchmark method for assessing a product’s environmental impact, and is widely recognized in the scientific community. This approach underpins a number of benchmark studies, including that by Poore & Nemecek, whose data has fed into numerous comparative analyses, such as this infographic by Bon Pote.

Using LCA therefore seems a good starting point for Planet-score. However, we learn from the methodological note that some LCA indicators have been “withdrawn“, and others “modified“.

Thus, the indicators “toxicological effects on human health”, “freshwater ecotoxicity” and “depletion of water resources” have been removed“due to their lack of robustness“.

While this limit is indeed recognized for the “human toxicity” and “ecotoxicity” indicators, it is equally recognized for other indicators that have not been removed from the calculation, such as the use of fossil resources or the depletion of mineral and metal resources. In addition, the decision to remove the “water depletion” indicator is questionable, as it is considered sufficiently robust by the scientific community. However, water resource depletion is an indicator for which the performance of livestock farming is generally mediocre.

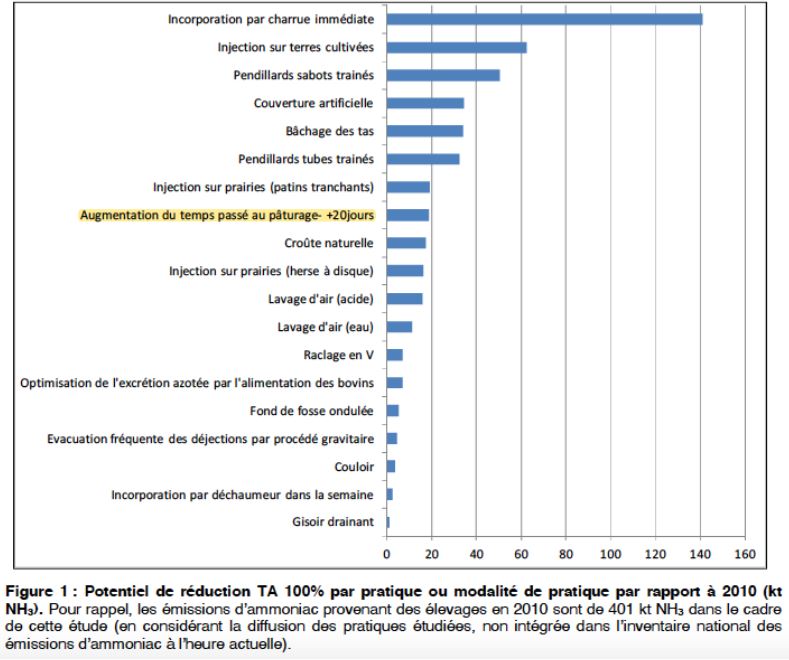

But this example is far from the only one that favors certain types of livestock farming. Indeed, Planet-score also applies a major modification to the LCA on ammonia emissions for livestock systems with access to the outdoors, on the grounds that these emissions would be “significantly reduced when dejecta occurs on grass surfaces (70 to 90%)“.

A statement that fails to source its figures and to mention other factors that also largely influence ammonia emissions, even for grass-fed livestock. The result is a downplaying of the impact of livestock farming on environmental acidification. When contacted, Planet-score indicated that these figures were taken from this ADEME analysis and this publication, dated 2013 and 2005 respectively.

The 90% figure from the ADEME study compares two archetypes of complete and opposing systems (integral grazing versus intensive building systems), and not the marginal effect of additional grazing days in a mixed system, as suggested by Planet-score’s “pro rata” approach. Above all, the study classifies increased grazing time as a relatively ineffective lever.

Land use, climate change…

On land use, Planet-score makes the questionable choice of excluding permanent grasslands from the feed/food competition calculation, i.e. it considers that grasslands grazed by ruminants (cattle, goats, sheep, etc.) do not constitute a use of agricultural land. The reason: these meadows are“very rarely used to produce anything other than grass” – a simplistic assertion that masks other virtuous uses that can be made of the land (e.g. reforestation), and overlooks the fact that, on a global scale, cattle farming is much more a cause of biodiversity loss than of its protection.

As a recent article in Nature Food pointed out, the impact of ruminant meat“on species extinctions is about 340 times greater than that of cereals, by mass, and about 100 times greater than plant-based proteins such as soy and other legumes.”

But by far the most significant change concerns the “Climate Change” indicator, which has the highest robustness score of the LCA method. Let’s take a look at two processes that could minimize the impact of methane on climate change.

Process 1: diverting attention from ruminant methane

Ruminants emit methane, mainly through their burps. This gas has a double impact on the environment: through its direct greenhouse effect, but also indirectly – it is a precursor to the formation of ozone, both a greenhouse gas and a pollutant. Since pre-industrial times, methane has thus emerged as the second-largest contributor to global warming after CO₂: on its own, it is responsible for a temperature rise of +0.5°C, or 30% of recorded global warming.

However, “Planet-score is deliberately trying to divert attention from methane emissions, which seems very worrying“, warns Valérie Masson-Delmotte, co-chair of IPCC Group I between 2015 and 2023. Interviewed for this article, she denounces “a biased presentation of the state of knowledge, in a supposedly scientific form.”

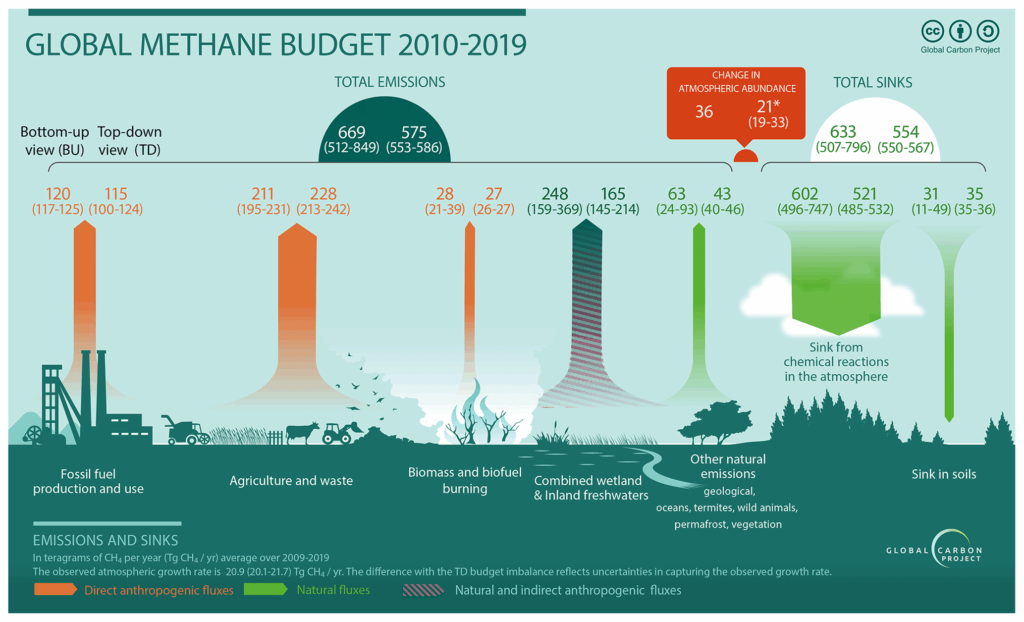

The insert on page 18 of the methodology is scientific misinformation, since Planet-score asserts that“methane emissions currently observed are predominantly of fossil origin, linked to the worldwide exploitation of oil and gas”. This assertion is contradicted by numerous studies, including the Global Methane Budget 2025, which points out that methane emissions from agriculture are almost twice as high as those from the fossil fuel sector worldwide. This diversion towards fossil emissions, totally out of place in a food assessment tool, echoes a recurring strategy of the meat lobbies, which consists in relativizing the responsibility of ruminant farming on the grounds that “there are other things to worry about”.there are other things we should be more concerned about“.

But Planet-score goes even further, since methane’s contribution to climate change has been divided by 2 through the use of a controversial metric called “PRG*” (pronounced “PRG star”).

Process 2: using the GWP* metric to minimize methane’s impact on the climate

For the same quantity emitted, methane causes more intense global warming thanCO2, but over a shorter period. These differences can make it difficult to compare the impact ofCO2 and methane emissions on the climate, and have led to the development of several indicators. The worldwide reference method, known as “GWP100”, involves measuring the “Global Warming Potential” of a gas against that ofCO2 over a period of 100 years. Using this calculation, methane’s GWP is equal to 27, which means that 1 tonne of methane emitted warms the climate around 27 times more than 1 tonne ofCO2.

However, Planet-score has chosen to adopt another tool: the GWP*, developed by Myles Allen and his team to account for methane emissions in a different way. Unlike the GWP100, the GWP* value increases when emissions increase, and decreases when emissions decrease – regardless of the absolute value of those emissions. Thus, a gradual reduction in methane emissions is sufficient to consider that it contributes “to no additional warming”.

Diverted from its original purpose, GWP* can go so far as to justify “climate neutrality” objectives without any real reduction in emissions. Valérie Masson-Delmotte proposes the following analogy Imagine someone who drinks a bottle of cognac for breakfast every morning. A GWP* metric would note that this person maintains a stable blood alcohol level over time, and doesn’t become drunker from one month to the next: he or she remains at a constant level of drunkenness. According to the logic of the PRG*, this person could claim “alcohol neutrality”. But this would tell us nothing about the effect of this stable alcohol consumption on her health, her ability to work, her driving ability, and the risks for her and society as a whole. “.

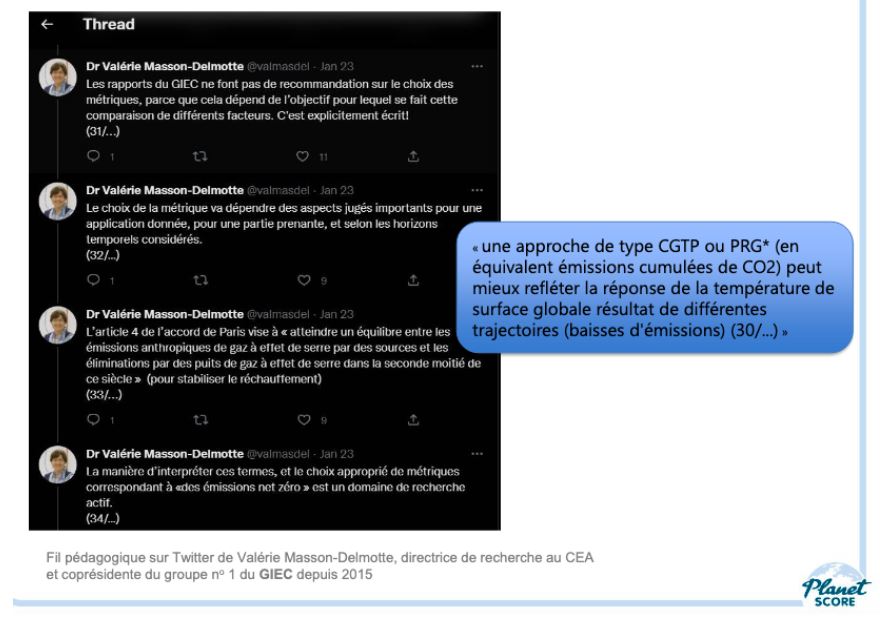

An example of cherry picking condemned by Valérie Masson-Delmotte

When asked about the application of GWP* in their methodology, the Planet-score teams point out that their calculations lead to a value of 13.8 for the GWP of methane, i.e. a division by 2 of the impact of this gas on global warming compared with GWP100. Planet-score justifies this choice by stating that“the IPCC has not ruled in favor of either metric, and even specifies that the GWP* […] can improve quantification of the contribution of gases to global warming (rising temperatures)“. In an online presentation of its methodology, Planet-score even goes so far as to cite Valérie Masson-Delmotte’s comments in support of this bias.

Valérie Masson-Delmotte condemns Planet-score’s distortion of her words and misuse of the PRG*. : “This is a truncated quote froma long Twitter threadand distorts the complexity of the choice of metrics. Using this quote to justify an arbitrary methodological choice that is not supported by a scientific publication, as should be the practice for indicators provided to consumers, is very surprising”. He added: “I’m also very surprised to see that the argument justifying the Planet-score methodology even calls into question the importance of reducing methane emissions to limit global warming. Although this point was made at the very beginning of my Twitter feed, it disappeared from the Planet-score presentation”.

Scientists have been warning for several years about the misuse of GWP*, pointing out, for example, that it is a relevant tool as a model, but not as a metric. As the High Council for Climate : “the use of GWP* is not suitable for life-cycle analyses or carbon footprint calculations, since a drop in emissions over several decades gives a negative value to GWP*, which would encourage the consumption of products releasing methane into the atmosphere, as soon as these emissions decrease”. Visit conclusions of the IPCC assessment emphasize that “if life cycle analysis conclusions are sensitive to the choice of emissions metric (type, time horizon), the results must be communicated very cautiously“.

Recent surveys carried out by Desmog and Novethic have shown that this use of GWP* represents a real boon for the red meat and dairy industries: “with this new calculation, companies and countries can declare themselves ‘climate neutral’.climate neutralwith low emissions reductions of around 0.3% per year, well below what scientific assessments recommend“. In France, the cattle lobby INTERBEV, which has given its public support to the Planet-score from 2021, has regularly expressed its interest in the PRG*.

NEWSLETTER

Chaque vendredi, recevez un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

+30 000 SONT DÉJÀ INSCRITS

Une alerte pour chaque article mis en ligne, et une lettre hebdo chaque vendredi, avec un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

Stage 2: score compression blurs major differences in impact between products

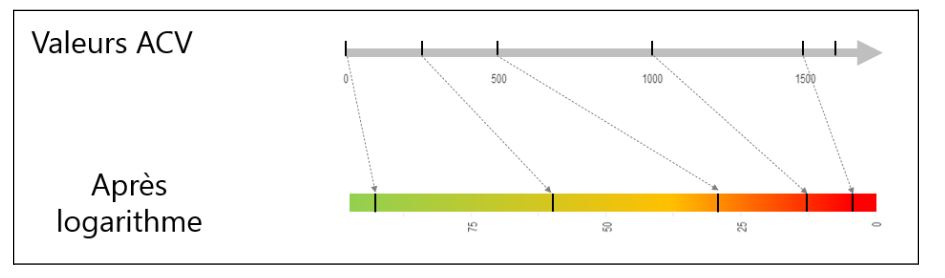

The use of LCA can result in highly contrasting environmental impacts depending on the product: a beef steak , for example, has an overall impact 30 times greater than that of tofu, according to Agribalyse. To transfer these differences to a label offering just 5 grades from A to E, Planet-score transposes the LCA scores onto a closed logarithmic scale from 0 to 100.

As Anne-Claire Asselin, an environmental and biodiversity expert who contributed to the initial Planet-score methodology via her consultancy SAYARI, explains, this mathematical transformation “attenuates the high LCA values while creating a zoom effect on the small ones”. Anne-Claire Asselin points out that SAYARI withdrew from the Planet-score project in August 2022 “due to scientific divergence“.

Source: Anne-Claire Asselin.

The logarithmic method is therefore intrinsically favorable to products with a high environmental impact (such as meat products), which see the gap that initially separated them from vegetable products narrow considerably.

Step 3: Allocate unjustified bonus-maluses

After modifying the LCA and compressing the scores, Planet-score applies 13 additional parameters to these scores, which are similar to bonus-malus assessing “systemic issues” in an approach inspired by planetary limits.

Editor’s note: we add colors.

While the approach is not without interest, no argument is provided in the methodological note to justify the addition of these 13 specific parameters to those of LCA. When questioned, the Planet-score team replies that these indicators “have been determined to cover all areas, in particular those of – very numerous and very important – missing from the LCA“. A questionable explanation, since at least 7 of the 13 parameters added by Planet-score are in fact already taken into account in the LCA used by Agribalyse, which serves as the starting point for Planet-score’s calculations. Applying these 7 parameters to products means double-counting the environmental impact of air transport, heated greenhouses, synthetic fertilizers, imported deforestation, packaging, irrigation and the carbon storage of grasslands.

In addition, the bonus-malus values are questionable, as their weight (-25, +20, etc.) overwhelms the values on the logarithmic scale between 0 and 100, as deplored by the Conseil scientifique pour l’affichage environnemental, chaired by INRAe and commissioned by the government. Anne-Claire Asselin agrees: ” the logarithmic approach […] works very well for inter-category differences, but Planet-score then applies bonuses and malus after applying the logarithm. This calculation method creates a large intra-category magnifying effect, enabling even beef to obtain note A“.

An unexplained number of bonus and penalty points on the Planet-Score methodology

Despite our questions, we were given no quantified explanation to justify the values attributed to these bonus-malus. For example, using ingredients associated with imported deforestation can only penalize a product by 4 points. Could this be because livestock farming is one of the main causes of imported deforestation? It’s impossible to know, since the way in which the bonus and malus values are decided is not specified either in the methodological note or in the reply sent to us.

For the “Biodiversity at plot level” indicator (which can bring a considerable bonus of 20 points), Planet-score relies on “BioSyScan”, a diagnostic tool that assesses the potential impact of farming practices on biodiversity at farm level. Owned by the same endowment fund as Planet-score (Solid Grounds Institute), its The methodology has not been the subject of any scientific publication, and a scientific group including ADEME and INRAe recently concluded that the application of BioSyScan was “not compatible“. with Agribalyse data derived from LCA, which is what Planet-score does.

Questioned on this subject, Planet-score points to a positive evaluation of BioSyScan by the Comité d’expertise scientifique interdisciplinaire sur l’affichage environnemental (CESIAe), a group of researchers with no institutional recognition. Its output is limited to 3 non-peer-reviewed reports, in which the defense of Planet-score features prominently. Contacted, CESIAe states that it was formed at the invitation of UFC-Que Choisir to the French Ministry of Ecological Transition, and denies any contractual or collaborative link with Planet-score.

How does Planet-Score rate pesticides?

In the case of pesticide use, which represents the biggest penalty (up to -25 points), it is specified that “the development of this indicator is the subject of specific work with a view to publication“. When questioned on this point, Planet-score refuses to divulge the details of this methodology, citing“intellectual property rights protecting it” and the need to“preserve its know-how“. The organization compares its approach to that of UFC-Que Choisir for food additives or WWF for fisheries. This response raises questions: how can we verify the robustness of a calculation whose formula remains a secret?

Finally, we note the way in which extensive livestock farming is once again favored through the bonus points granted to permanent grasslands “insofar as the return of these areas to arable crops would represent a significant destocking of GHGs (CO₂)” according to the methodology.

Over and above the double-counting problem described above, scientific literature shows that permanent grassland does not sequester carbon indefinitely, and certainly not enough to offset the methane emissions of the ruminants that graze on it. While it is therefore necessary to ensure that current grassland is not transformed into crops, it is tricky to rigorously justify awarding bonus points in this way to products from extensive livestock farming, which remains a net contributor to global warming.

Planet-Score: a questionable choice of guests and communications strategy

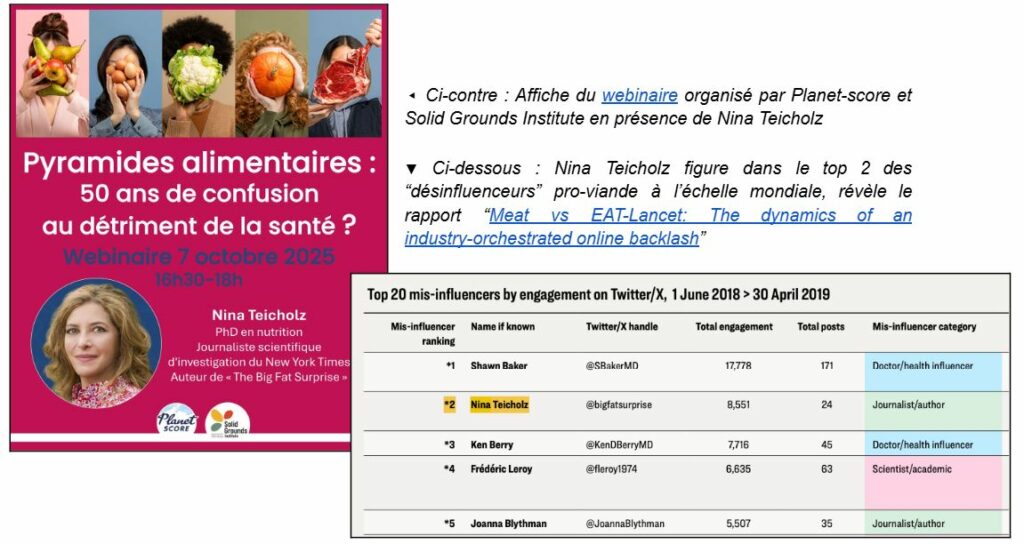

Planet-score recently invited journalist Nina Teicholz to one of its webinars, where a recent report revealed her to be the world’s second leading pro-meat “disinfluencer”. Following the controversy generated by this invitation, Planet-score justified its choice by sending an e-mail to webinar participants, stating that Nina Teicholz was “free of any conflict of interest and has no links with any industry, economic sector or ideological current“.

According to Planet-score, the journalist is “one ofa number of experts currently being targeted by a hate campaign aimed at preventing any discussion of the substance of nutritional issues”. In particular, Nina Teicholz maintains that the obesity rate in the United States has risen as a result of vegetarian diets and the decline in meat consumption, and promotes the “baby carnivore” trend.

Image 2: Nina Teicholz is one of the top 2 pro-meat “disinfluencers” worldwide, according to the report “Meat vs EAT-Lancet: The dynamics of an industry-orchestrated online backlash“

President and spokeswoman for Planet-score, Sabine Bonnot’s rhetoric is very similar to that of the meat industry. For example, in a recent interview for “Le Monde”, she asserts that “according to Planet-score’s calculations, [extensive ruminant] livestock farms are even ‘the only ones with the capacity to be net storers’ of carbon, which means they would have a positive climate impact“.

A myth debunked but regularly repeated by the meat industry, which claims that grass-fed beef has a positive impact on the climate. However, an article published this year in the prestigious journal PNAS reminds us once again that grass-fed beef emits just as much greenhouse gas as industrial beef.

Conclusion: what to make of Planet-score?

Planet-score is not without its qualities. Its inclusion of farming conditions, its willingness to go beyond the recognized limits of LCA, and the clear legibility of its labels all bear witness to a commendable ambition.

However, this environmental label has major methodological flaws: incomplete scientific references, addition of bonus-malus causing double counting, lack of justification for the number of points attributed to each bonus-malus, etc.

Methodological choices such as the misuse of GWP*, as well as certain elements of Planet-score’s communication, even tend to minimize the need to reduce our meat consumption in order to limit global warming. This imperative is well established by scientific consensus, which stresses that global methane emissions must be halved by 2050 to limit global warming to +2°C by 2100.

The climate emergency and the biodiversity crisis call for environmental assessment tools with a transparent, reproducible and scientifically validated methodology. For an environmental label whose results deviate from the scientific consensus would run the risk of not fully fulfilling its mission: guiding citizens towards truly sustainable food choices.

Authors :

- Tom Bry-Chevalier, doctoral student on the environmental and economic challenges of alternative proteins

- Victor Fighiera, consultant-trainer on agricultural and food issues, organic food producer