For the last few weeks, we had plenty of demands for a critical analysis on Kate Raworth’s “Doughnut Economics”, which had a rapid acknowledgement and incredible positive feedback in a short amount of time. But what is it about, concretely ? What are her propositions ? How are they different from classical economic theories ? Here is the time to take a closer look at this theory, that draws a ruthless picture of the current situation, and propose some stunning and innovative ideas.

Author and English translation : Vincent Lavilley

A DOUGHNUT? ARE WE REALLY TALKING ABOUT ECONOMICS ?

The theory called “Doughnut Economics” was invented by an English economist, Kate Raworth, who was wishing to eradicate poverty and to put an end to environmental destructions.

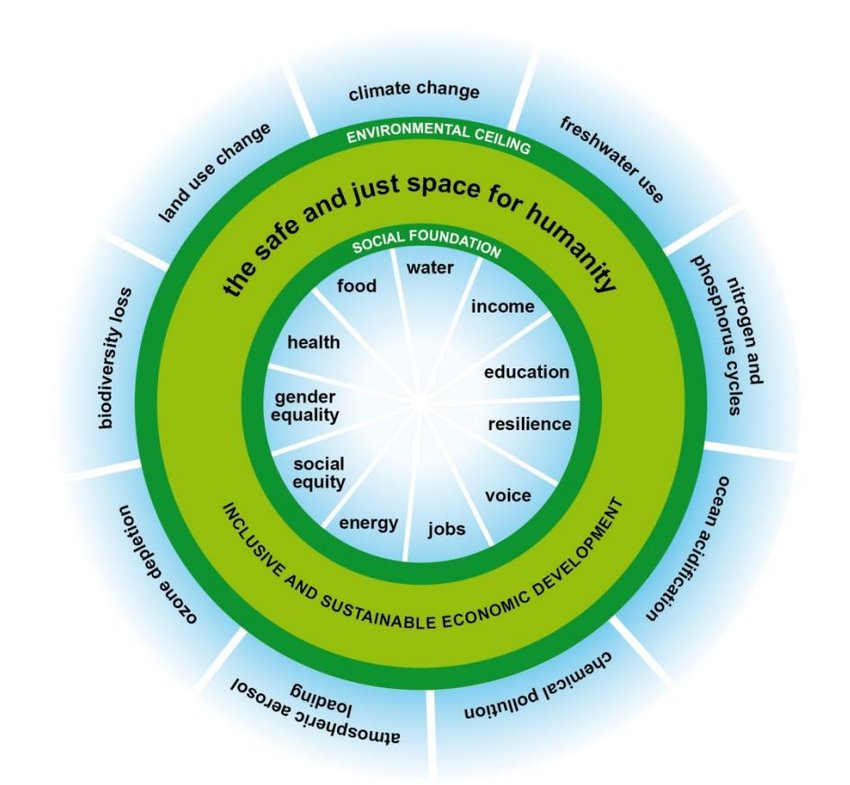

After three years spent trying to improve the life of local inhabitants in Zanzibar, she hopped into the United Nations in the U.S.A., on the team writing the annual flagship Human Development Report. After four years of witnessing barefaced power games block progress in international negotiations, she finally left to fulfill a longheld ambition and works with Oxfam for over a decade, in the early 2000s. It will be in this organization that she will find the means to act against inequalities and world poverty. After a year of maternity, she felt the need to come back to the very basics of economics, as it shapes our modern world in its whole dimension. She reads the classics, gather some ideas to bring out a general reflection and starts to draw what should be humanity’s long term goals. She builds her theory in 2012, drawing two circles forming the shape of a doughnut. The doughnut shape comes from the integration of two limits :

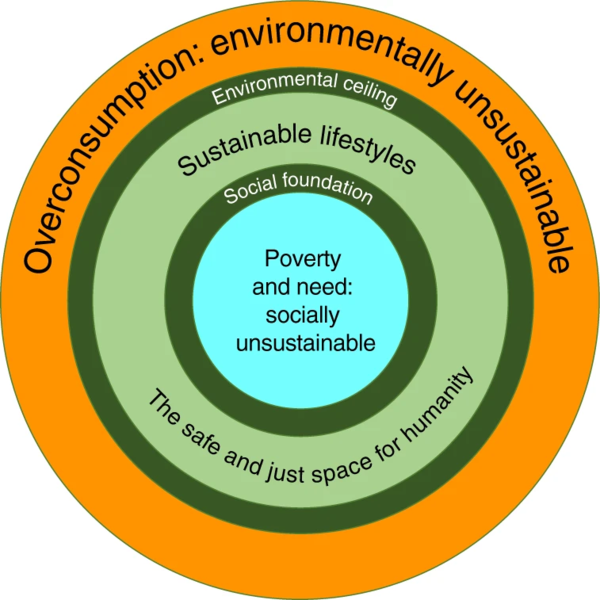

⦁ an inner limit – the social foundation – that represents the basic needs for any human being that must be satisfied (hunger, thirst, illiteracy, etc…).

⦁ an outer ring – the ecological ceiling – that we should not cross in order to preserve our environment from degradation (climate change and biodiversity loss).

Between those two rings is the doughnut itself, the space in which we can meet the needs of all by respecting what the planet can “offer and handle”.

It will require 3 more years of researches and personal thoughts to build a coherent ensemble and give more depth to her theory, published a book titled : “Doughnut Economics : Seven ways to think like a 21st century economist”. In this book she gives details and new ways to understand the social and biophysical reality of our modern societies, and proposes ideas to tackle the numerous challenges humanity will have to face in the coming decades : climate change, resources depletion, increasing inequalities, environmental pollution or biodiversity loss.

SEVEN WAYS TO THINK LIKE A 21st CENTURY ECONOMIST

Raworth makes a harsh observation on the academic field of economics and its recent evolution : it didn’t open up to other fields, remained based on convenient, beautiful but unproved assumptions (such as the infinite growth or decoupling) instead of realistic and reproducible experiments (such as the central role of energy, the finiteness of resources or the capability of humanity to deeply disrupt/devastate its environment). This divergence took the economic field away from the physical reality and prevents us nowadays to put in motion the actions to solve the issues that, we humans, will face in the close future. Briefly resumed, the cognitive model of our societies doesn’t work properly and isn’t adapted to our environment anymore.

To change this “mental software”, she proposes a list of seven principles that must be modified within the economic field in order to evolve from an archaic and outdated vision, with fragile fundamentals, to a modern, rigorous and more coherent one.

1st principle : Change the goal

20th century economics is focused on a macro-economic indicator called the Growth Domestic Product (GDP) that possesses numerous defaults and biases. We must go beyond this obsolete vision from the past in order to build a new goal for humanity, as proposed by the doughnut.

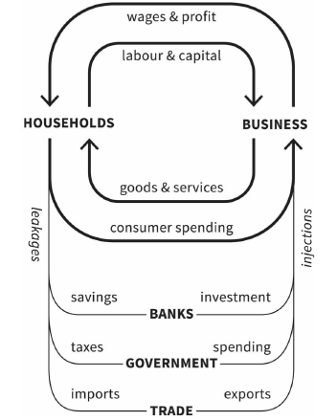

2nd principle : See the big picture

Mainstream economics depicts the whole economy with a limited image, the Circular Flow Diagram. These limitations have fed the neoliberal narrative on market efficiency, the incompetence of the state or the tragedy of the commons. We need to draw a new economic pathway which would be better integrated within society and environment.

3rd principle : Nurture human nature

20th century economics revolves around the notion of Homo Œconomicus : a cold, rational and calculating individual whose decisions are only directed toward a maximized profit, granting him a dominating position over a chaotic and wild Nature. This vision forgets that humans are a part of Nature, one of its many links, that they are social animals subject to a plethora of cognitive biases which will affect their every decisions.

4th principle : Get savvy with systems

The economic field didn’t venture and try to investigate far from its fundamentals, described in the 19th and 20th centuries, when it stole and copied from the mechanical physics, in order to claim the same authority of natural sciences. A more intelligent and comprehensive approach would integrate modern discoveries such as thermodynamics or complex interactions which are the core basics of systems theory, notably with the notion of feedback.

5th principle : Design to distribute

During the 20th century, a simple representation delivered a strong message about inequalities with the Kuznets curve : we will go through a tough time before reaching a clear improvement with a reduction of inequalities, due to economic growth. In fact, it appears that inequalities are not a necessity/feature, but a failure in the conception of the economic model. This means we need to invent new models to better redistribute wealth, and a new method for money creation.

6th principle : Create to regenerate

The economic theory has explained, for a long time, that a clean and proper environment was a luxury only reserved to the richest. This view is reinforced by the Kuznets curve which, this time again, displays the trajectory to reach a better future : we’ll have to go through the worse before it gets better, and when the economic growth will (maybe) clean the world out of its pollution. Such a law doesn’t exist in the physical reality : ecological degradations are the consequences of industrial conceptions. 21st century economists will have to build a circular (and not linear), regenerative model in order to bring humanity back in the natural cycles of the Earth.

7th principle : Be agnostic about growth

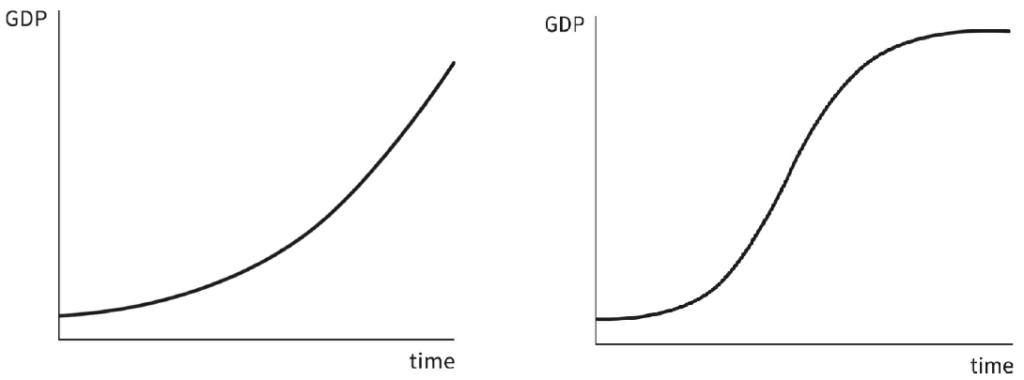

There exists a simple but frightening picture that is never drawn in the general economic theory : the long term trajectory of GDP growth. Mainstream economics see growth as a vital goal, when in reality, nothing grows forever in Nature. Discarding the GDP indicator could be easily achieved, but the addiction to growth remains hard to overcome. We need societies in which humanity can thrive and blossom, not one that will grow forever by putting a never ending stress on its individuals. This radical change leads us to become agnostic about growth, and to build a society that can function financially, politically and socially in a world where we learn to evolve without growth.

On the left side, a curve representing an exponential function, endlessly growing without any limit. On the right side, a curve representing a sigmoid function which will reach a maximum/optimum (also called a S curve because of its shape). We easily comprehend that an infinite growth will cause global and major troubles for humans, by quickly overshooting the planetary boundaries of what the environment can absorb. It is then mandatory to structure our societies (and therefore, our economies) so as to incorporate evident and clear limitations, as proposed by the doughnut : a “lower” limit for basic human needs and a “higher” limit for the planetary boundaries (figures from the book).

RUPTURE WITH (NEO)CLASSICAL ECONOMICS

These 7 principles are in total contradiction with our modern mainstream economy, the neoclassical economics. It begins at the end of the 19th century, when economists tried to copy and mimic physics by an intense use of mathematics and formulas to describe socio-economic phenomena. This conception will transform the economic field which will now produce a plethora of models that are supposed to represent our world (with “a few” simplifications and some “negligences”), to place themselves in totally unrealistic conditions, deny human and ecological aspects to specifically focus on the financially and monetary aspects of human societies.

Raworth’s whole book will detail and explain how the economic theory from the last century has been built around growth as a societal goal, and the consequences of a never ending human, economic, financial activity. She reviews the recent history of neoliberalism, the assumptions taken for granted (infinite growth, efficiency of the market, destabilizing role of the state, disregard for the commons) as well as its obvious errors (missing role of energy, resources and biodiversity in the productive factors, management of wastes and pollution).

We can understand with ease the risk of over-teaching this school of thought in our universities : we will condition students with an archaic model unable to cope with serious and global problems that will affect the whole humanity. Political, economical, financial or industrial actors of tomorrow will take their responsibilities with an outdated cognitive model, in total contradiction with the environment they are evolving in. This will intensify the socio-ecological troubles and prevent any possibility for a change, as the executive managers/directors won’t be able to assess the discrepancy between their view of the world and the actual physical reality. Given the complex, quick and uncertain changes that we are going to face, it is highly presumptuous to propose laws, institutional frameworks or policies that would easily solve all these issues.

In this sense, the book seeks to gather innovative and emerging ideas to create a new state of mind, in perpetual evolution, freed from assumptions which might have worked in our great-parents’ world, but is absolutely outdated nowadays.

NEWSLETTER

Chaque vendredi, recevez un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

+30 000 SONT DÉJÀ INSCRITS

Une alerte pour chaque article mis en ligne, et une lettre hebdo chaque vendredi, avec un condensé de la semaine, des infographies, nos recos culturelles et des exclusivités.

SOME IDEAS TO CHANGE THE SYSTEM ?

In the last chapters of her book, Kate Raworth offers us a few audacious tracks to try jamming this deadly dynamic and to find a more environmentally respectful path.

1. Make the virtuous companies profitable

Today, the companies with the highest profits are those which are not restricted with or do not care about social or environmental regulations. The companies which try to give a better pay to their employees, to preserve the environment or the biodiversity are not supported/boosted by the system. On the contrary, they are engaged in an unfair competition and struggle to make their economic model profitable. John Fullerton and his colleague Tim MacDonald have thought about a way for regenerative companies to act out of this constant pressure for profit coming from the shareholders. They propose a concept that delivers acceptable and resilient financial returns from mature low- or no-growth enterprises. Instead of paying profit-based dividends to shareholders, the company will pay a share of its income in perpetuity. According to Fullerton, this system would allow :“[…] an enterprise to behave like a tree ; once it is mature, it stops growing and bears fruit – and the fruit are just as valuable as the growth was.” The pressure exerted by shareholders remains one the many manifestations of how the search for financial gains orients our economy toward an endless growth. Lessening this aspect or abolishing it would be a first step in the path leading to the end of this insatiable need for growth.

2. A new method for money creation

Another face of the infinite growth resides in the money creation. As opposed to any object in our universe that will rot, rust or wear out, money can accumulate endlessly thanks to interests. To prevent this effect, Raworth suggests a currency bearing demurrage, a concept invented by Silvio Gesell in the early 20th century. Behind this term, we find the idea of paying a small fee for holding money. In other words, if I keep my money in my wallet or my bank account, I would have to pay a small fee to avoid it losses in value. This would mimic the natural process in our universe, where energy is needed to maintain some systems in their state (such as complex system like living beings). Such a system of money creation would be a fundamental disruption in the core of our societies as the research for profit would no longer be associated with growth but oriented to the conservation of the value.

This new form of money would lead to long-term investments and reinforce regenerative activities, as opposed to the current short-term maximized profits and high growth rates. The idea of a ‘melting’ currency can frighten and deter, but one need to keep in mind that we are currently living in such a world : most of the central banks have negative rates (Japan, Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland and the ECB) that act as a melting currency, because savers must pay the banks to store their money.

3. Define new socio-economic indicators

The GDP is not complete and sufficient measure to represent the state of our societies and our planet. The inventor of national accounting using the GDP, Simon Kuznets, had already perceived its limitations when he created it, and exposed them to the U.S. congress in 1934. This indicator overlooks various vital aspects such as well-being, education, health or the right to a clean environment. It also fails to integrate natural resources, wastes, species richness or the stability of planetary systems like our atmosphere. Thus, we need to define new indicators to quantify these states that would inform us and allow us to anticipate, predict and avoid these catastrophic changes. (see these reports from the European Commission ; the OECD ; the WEForum). An organization like this would drive us toward more appeased, fair and united societies.

RECEPTION AND CRITIQUES

The book was well received after its release. Most of the commentaries praised the innovative spirit of the theory and its search for human well-being along with the respect of the environment.

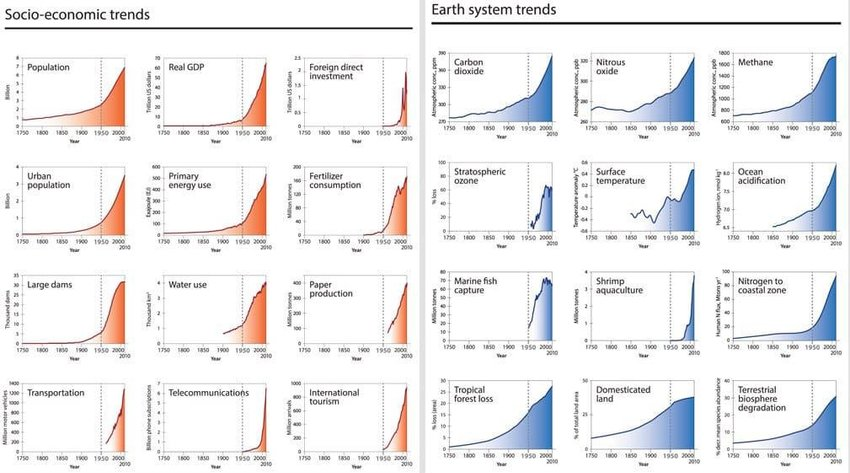

⦁ In the kingdom of the one-eyed men, the blinds will remain kings

Most of the negative reviews come from economists of the neoclassical school and pro-business individuals, whose arguments have already been debunked and/or disproved, notably in the book they are supposed to have read as they are criticizing it : the reject of Homo Oeconomicus (the market is perfect and optimally allocates resources, yet, it creates financial bubbles) ; the end of the GDP indicator as a political and economical goal ; the benefits of growth on poverty which remains around 10-20% of the population in the wealthiest countries ) and on the environment (see the figure below, which shows how various trends in our system Earth are increasing exponentially)

⦁ An incomplete and debatable methodology

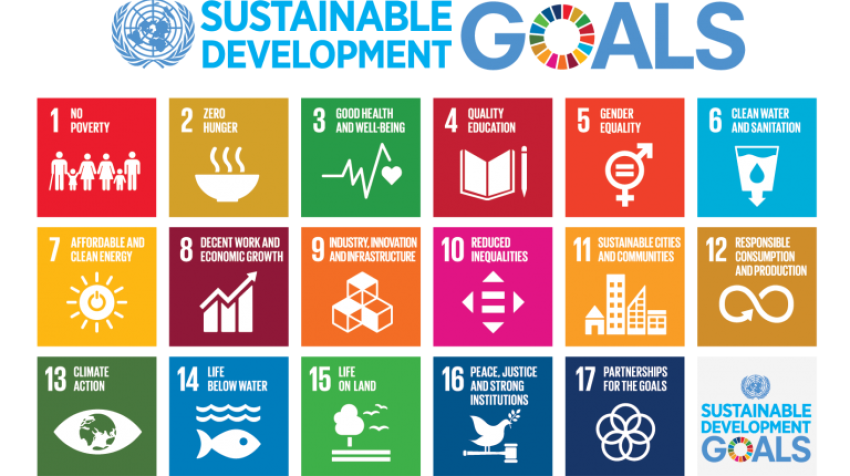

Some reviews are more concerned about the methodology, which is not entierely described and characterized due to the recent birth of the concept and the obvious lack of academic researches out of the GDP/growth framework. Indeed, the pertinence of the chosen indicators constitues one of the most important and central point in the application of the Doughnut Economics. As an example, the social indicators selected are those of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) of the United Nations (U.N.) which will shape the inner/lower social limit, but can cause some problems in their application: definition and methodology, range of application depending on the political regime, non economic nature of some criteria (that doesn’t mean they are not important, but they must be modulated by social policies rather than economical ones).

Bill Scott explains that, according to himself, social and environmental limits don’t share the same dimensions : social boundaries such as poverty rate are human constructions, whereas ecological boundaries are physical walls : while the former can evolve and be measured relatively, the latter are set once for all and we cannot negotiate them.

⦁ Put and end to growth but not totally

Besides, using the SDG remains troublesome as the 8th objective firmly asserts that growth is a vital necessity for humanity. If growth can be acceptable in developing countries, in certain areas or at specific times, we cannot keep on using it as a trajectory as Raworth explained it in the book. The representation of the doughnut mentions income and work without describing in details what lies behind these terms.

We could also question the blurry vision on growth if we apply the doughnut : will it slow it down, regulate it or preserve it ? Will it allow a spatial modulation (depending on the country) and/or a temporal one (depending on the time) ? If we follow thediscussion between Kate Raworth and one of its reviewers, she mentions the necessity of an economic growth in poor countries in order to reduce the gap with rich countries and catch up with them, but warns that it could end up being an infinite quest for growth, the very same way developed countries have set it as their main societal goal.

Nevertheless, we could question what would be the means of this growth and the method to check the consequences : how to assess the countries will not cross the boundaries, how to determine if some can be temporarily crossed for the construction of infrastructures, transportation network or for agriculture development ? In addition, the concepts of progress and growth are firmly linked to a western cultural perception of economics, that could be challenged in other societies not so deeply rooted in these values, and which still possess a strong relation with their environment. These are sensible but central questions that will require time, experience and testing so we can finally answer them.

⦁ Better characterize and sharpen the ecological boundaries

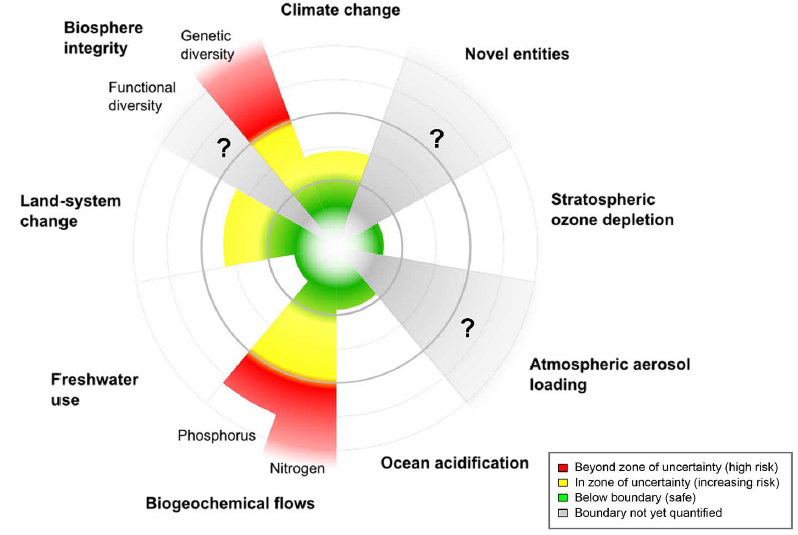

Concerning planetary boundaries, Raworth used the academic work of Swedish scientists from the Stockholm Resilience Center. In 2009, the director of this research center, Johan Rockström, led a group of 28 scientists in order to identify the processes that regulate Earth stability and resilience. They proposed a quantitative measure of planetary boundaries within which humanity can prosper and continue to develop.

These boundaries provide us with a quantitative and qualitative framework, with a rigorous view on our societies’ impacts on the environment : crossing these boundaries would mean overshooting the sustainability our environment can provide, and would encourage us to modify our methods for production/consumption. These boundaries are getting considered and taken into account by various states and organisms (UN, EU, France), even if they give rise to criticism, as any model would.

The theory around the doughnut has been re-used and improved by a group of English economists from Leeds, composed by the teams of Daniel O’Neill and Julia Steinberger. They added up some enhancements, responding to previous criticisms, and they improved the methodology, providing us with a computation for many countries, displaying their place within the doughnut (data are accessible on their website).

⦁ And now, what do we do with the doughnut ?

To conclude, we can regret that Kate Raworth barely explains the role the doughnut will have if it becomes a reference in our economies : will it just act as a compass for political actors, just like are the various modern indicators and scientific advice, will it incorporated into the legislation to define a proper state and legal framework, benefiting from legal applications and controls ? In the same way, she doesn’t give any indication on how to administrate a country without growth, and never details the modifications that would result in other areas such as urbanism, transportation, energy, agriculture, tax law, state budget, etc…

Another subsidiary question remains unanswered : what is her position and how does she position herself within the different trends in ecological economics such as post-growth, degrowth, bioeconomics ? Does she share common values with them ?

One could also perceive a certain shyness in her declarations, despite the strong and assured tone on the social and ecological issues. What solutions to tackle climate change? How to manage the balance between developed and developing countries ? Which repartition for the political, legal, financial load to handle between these countries ? What tools, what structures ?

All of these questions will require time, advanced thoughts and feedback to determine what are the best relations between the fields involved, the most adapted solutions to local or global concerns, their acceptation or their validation by complex social and political movements, in an uncertain future.

WHAT CAN WE CONCLUDE ABOUT THE DOUGHNUT THEORY ?

The work proposed by Kate Raworth is certainly the most interesting in various directions :

- It is a well sold book that call classical economics into question (the very same leading us into a disaster). Its reach and good reception show that people’s minds are ready for a large change in the system. A few cities such as Amsterdam and Brussels, as well as Ireland, have shown a profound interest into applying the doughnut on their territory.

- The innovative model described by Raworth leads us to a more equitable, fair and environmentally respectful world. The book firmly keeps an optimist tone and gives us a few paths to change our societies, to drive it toward a more mature, sustainable and resilient state.

- This theory adds an exotic touch in a closed and narrow-minded field, whose solutions are closer to prayers and utopia, without any real consistency.

- This work creates bridges between researchers of numerous and various fields (especially in natural sciences), which is a serious deficiency in economics. The theory of “Doughnut Economics” is already in a phase of improvement by these researchers, and global networks are getting built following these ideas, in UK, Sweden and France. But we still need to create the connections between the different trends which share the same observations in the economic field, in order to reach a critical mass that could influence future decisions in politics, for the coming decades.

As Kate Raworth repeats all along her book, the doughnut is not a solution in itself, but a collection of ideas to progress toward a fairer and more sustainable world. Thus, it is out of question to list or impose these solutions. By understanding the limitations of this exercise, we can visualize the aim of her book. As a final conclusion, we are curious and excited to see if the “Doughnut Economics” will become another theory that will end up in a drawer, or if it will succeed to gather people around guidelines and policies, to consolidate its theoretic basis, to promote the birth of new economic models, new citizen’s initiatives, and if it will manage to link together the economists from the ecological economy trend, or even crazier, could convert those from other trends who are still stuck in the growth paradigm.

Her team has recently founded a research laboratory charged to improve the model, to sharpen the methodology and work hand in hand with local administrations. This feedback will be capital for checking the viability of the doughnut, as well as assessing the robustness of this approach which could be spread to other cities, or even to whole countries.

One Response

Correction: GDP is “gross domestic product” (1st principle).